THROUGH THE LENS: Praise the Fiddle

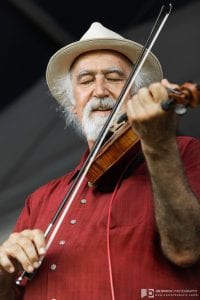

Rhiannon Giddens - ROMP Festival, Owensboro, KY - Photo by Amos Perrine

Fiddlers don’t fret. — Leanna Price, The Price Sisters

And fiddlers don’t fret over the differences between a fiddle and a violin either. Other than sometimes a half centimeter difference in the instrument’s bridge, they’re the same instrument. It’s amazing that the question is still being asked (even as recently as two weeks ago in the online journal Strings!).

But the focus of this column is not on the instrument’s technicalities or history. Rather, I want to highlight its ubiquity in roots music, the many forms it takes, and, as no article can do justice to all the extraordinary musicians in all genres, a few of the many notable fiddlers that we are so fortunate to hear.

The Fiddle in Appalachia

The fiddle arrived in Appalachia in the 18th century with immigrants from the British Isles, bringing with them the musical traditions of their countries. These traditions consisted primarily of English and Scottish ballads, which were essentially unaccompanied narratives, and dance music, such as Irish reels which were accompanied by a fiddle.

Appalachian fiddler Martha Spencer told me, “The fiddle is a part of the fabric of life in the community I grew up in. In our household, fiddle and banjo music was almost as common as breathing. My cousin Audrey Hash Ham made fiddles and would bring them over for my parents to try out. At local jam sessions with neighbors to dances to festivals and concerts, there were always lots of fiddlers.”

There are quite a few festivals devoted solely, or predominately, devoted to the fiddle. Most notably, in Appalachia: the Old Fiddlers’ Convention in Galax, VA, which will hopefully hold its 85th festival later this year; the Appalachia String Band Music Festival in Clifftop, WV, which aims to hold its festival in August; and the Kentucky State Fiddle Championship.

Fiddle Hell

However, even before those events, Fiddle Hell begins its 17th annual 4-day festival, (and the second to be held online) this Thursday, April 15. The Massachusetts festival has been a gathering of fiddlers, cellists, and other old-time players and singers to meet, jam, learn, listen, and have some fun. With 270 sessions and 100 different instructors the festival offers a plethora of styles and sub-genres of roots music from from gypsy to jazz. There is still time to register and complete information can be found here.

From Ed Haley to Laurie Anderson

The singular inspiration to a new generation of roots musicians John Hartford devoted the last decade of his life to the fiddle. He spent six years researching and writing a book on West Virginia fiddle legend Ed Haley, and recorded many of his tunes. Haley, along with Clark Kessinger, Blind Alfred Reed, and Edwin “Edden” Hammons, typified the depth of the early 20th century Appalachian style. That tradition continues today in such fiddlers as Rachel Eddy, Jesse Milnes, Bobby Taylor, and Tessa Dillon.

However, the fiddle was not unique to any one region of North America. Examples include Natalie McMaster of Cape Breton, Canada; Texas as typified by Bob Willis and later Asleep at the Wheel; Louisiana’s Cajun players such as the highly regarded Michael Doucett and K.C. Jones of Feufollet; and Mireya Ramos of Flor de Toloache, the groundbreaking all female mariachi band.

But the fiddle is more than an instrument in traditional music. In 1934 Stephane Grappelli formed the Quintette du Hot Club de France jazz band with Django Reinhart and continued playing until his passing in 1997. Many jazz players followed, including Ray Nance, who played with Duke Ellington, Regina Carter, Joe Venuti and Eddie South.

The fiddle has also played a role in the blues and blues influenced Black string bands such as The Mississippi Sheiks with Lonnie Chatmon, and Lonnie Johnson, Papa John Creach and more. Most recently, Anne Harris has played many blues festival but uses the blues as a starting point. By opening herself up to other realms a more apt description may be a cosmic consciousness that exhibits a spiritual, humanist philosophy.

The avant garde composer Laurie Anderson invented the tape-bow violin that uses recorded magnetic tape in place of the traditional horsehair in the bow, and a magnetic tape head in the bridge. Her 1982 debut Big Science album (just re-issued on LP) opened the door to the flourishing downtown New York music scene.

We’ve also seen how such Americana artists such as Amanda Shires, Lillie Mae, and Andrew Bird have used the fiddle as the basis of their unique take not just on the instrument but use it as the basis to stretch Americana’s boundaries as well.

Rhiannon Giddens, Bluegrass, and Beyond

While Kenny Baker remains the model for the traditional bluegrass fiddler, in the 1970s a new crop including Darol Anger, Barbara Higbie, Richard Greene, Laurie Lewis, and Jay Unger, came along and expanded the genre, with Vassar Clements bridging the gap. That set the stage for the seismic shift to come when a teenage prodigy soon became a household name — Alison Krauss.

Women in bluegrass had been bubbling beneath the surface for some time, but one could say that Krauss made it possible for more women to have their talents recognized. Today, these players include Sara Watkins, April Verch, Rayna Gellert, Noah Wall, Kimber Ludiker, Brittany Haas, Chloe Smith, Rosie Newton, Leanna Price, Carly Underwood, and all three Quebe sisters.

To illustrate the depth of the youth movement in women fiddle players, need look no further than Aila Wildman, who at age 15 won the Best All Around Performer award at Galax in 2018. Additionally, during my walks around the grounds of the many festivals I’ve attended during the past several decades I’ve seen many young girls playing instruments, usually the fiddle, alone or with friends.

Nor is the male-dominated country music industry immune: Jenee Fleenor broke that glass ceiling when, in 2019, she became the first woman to win the CMA Musician of the Year award, as a fiddler.

But the most significant fiddler of the past 15 years has to be Rhiannon Giddens who, first as a member of The Carolina Chocolate Drops and then solo and her collaborative work, pretty much singlehandedly revived the Black string band tradition, and reestablished the connection between Black musicians in bluegrass and traditional music. She’s also made some magnificent recordings, the most recent was released last week. Read ND’s review here.

Hurdles Remain For Women Fiddlers

I also realize that several columns could be devoted solely to women fiddlers. In the meantime we should note that women in bluegrass and other genres continue to face additional hurdles in pursuit of the music. An April 2020 episode of the NPR-distributed show With Good Reason was devoted to that issue. You should take the time to listen to it here.

However, Leanna Price, the fiddle half of The Price Sisters who are young, working, everyday bluegrass musicians, shared with me her perspective: “In high school, my twin sister Lauren and I didn’t really know any other girls within a 200 mile or so radius of our hometown who were interested in traditional Appalachian music. As with other customarily male-dominated fields, chances for women to pursue such interests were not always there. Today, however, there are more opportunities and resources available and female voices are more accepted than ever before. Each day I feel increasingly welcomed in the community as I grow in my professional career.”

Now, the photos. Click on any photo below to view the gallery as a full-size slide show.

- Alison Krauss – MerleFest – Photo by Jim Gavenus

- Amanda Shires – Photo by Todd Gunsher

- Anne Harris – Photo by Mark J. Smith

- Mireya Ramos of Flor de Toloache – Hardly Strictly Bluegrass 2019 – Photo by Peter Dervin

- K.C. Jones – Photo by Amos Perrine

- Savannah Buist of The Accidentals – Philadelphia Folk Festival 2018 – Photo by Mark J. Smith

- Barbara Higbie – 2018 -Photo by C. Elliott Photography

- Gordie MacKeeman – Blue Mountains Music Festival – Photo by Steve Ford

- Brittany Haas – Photo by Rick Davidson

- Andrew Bird – Bluesfest Byron Bay – Photo by Steve Ford

- The Quebe Sisters – Photo by John Rominger

- Rhiannon Giddens – ROMP Festival, Owensboro, KY – Photo by Amos Perrine

- Sara Watkins – Photo by Rick Davidson

- Anna Roberts-Gevalt – Photo by Amos Perrine

- Carrie Rodriguez – 2014 – Photo by Kirk Stauffer

- Rayna Gellert – Photo by Amos Perrine

- Bruce Molsky – The Metropole, Katoomba – Photo by Steve Ford

- Clark Kessinger – 1965 – Photo provided by Kim Johnson

- Young Fiddler- Shakori Hills Festival – Photo by Amos Perrine

- Leanna Price – Photo by Amos Perrine

- Carley Arrowood – Photo by Amos Perrine

- Leah Song – Rising Appalachia – 2015 -Photo by C. Elliott Photography

- Lillie Mae – Photo by Kevin Smith

- Martha Spencer – Blue Mountains Music Festival – Photo by Steve Ford

- Eleanor Whitmore and Doug Kershaw – Photo by Lisa Costantino

- Lillie Mae – FloydFest – Photo by Todd Gunsher

- Kimber Ludiker-Cayamo – Photo by Boom-Baker

- Michael Doucett – New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival 2015 – Photo by Jim Brock

- Katie Shore of Asleep at the Wheel – 2019 Photo by C. Elliott

- Natalie McMaster – Photo by Mark J. Smith

- Laurie Lewis – IMBA – Photo by Todd Gunsher

- Laurie Anderson – Photo by Amos Perrine

- Jenny Scheinman – 2020 – Photo by C.-Elliott

- Rachel Eddy – Augusta Heritage Festival – Photo by Amos Perrine

- Emily Miller – Augusta Heritage Festival – Photo by Amos Perrine

- Tessa Dillon – Mountain Stage – Photo by Amos Perrine