Malcolm Holcombe: An Appalachian Ghost Story

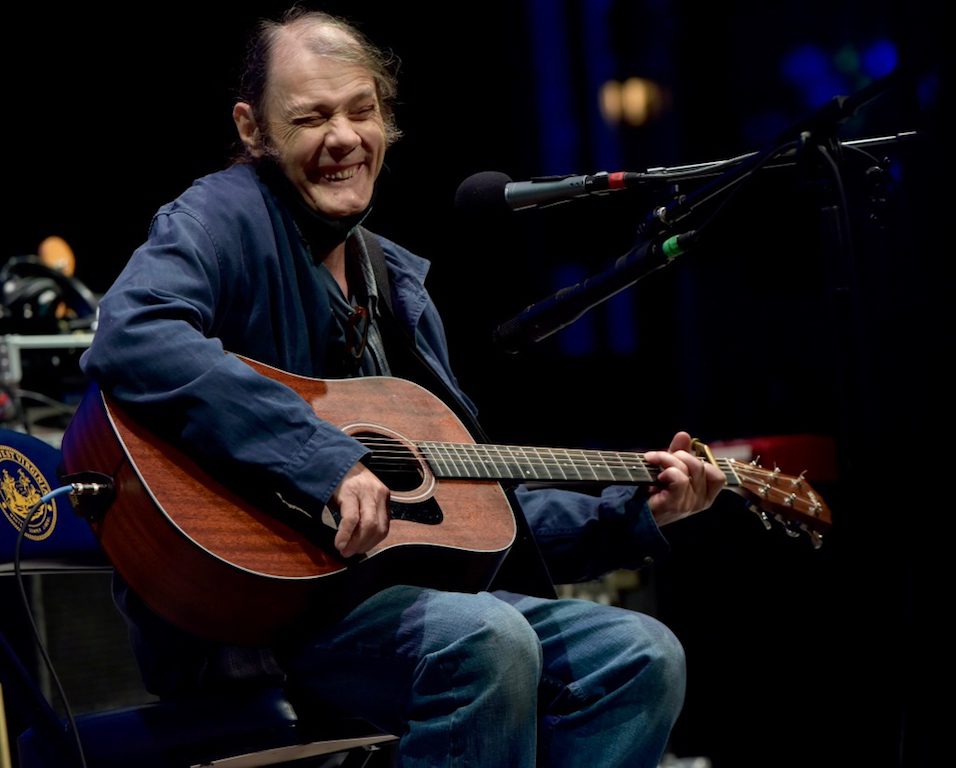

Malcolm Holcombe - Mountain Stage 2021 - Photo by Amos Perrine

I’ve never met Malcolm Holcombe, but he used to call me late at night. The phone would ring in the hours between midnight and 2 a.m., and I wouldn’t pick up. Calls at that hour normally involve romance, intrigue or tragedy. In the late 1990s, the first two possibilities weren’t possibilities. I would have needed some time to think about how to react to tragedy.

This happened several times. I had an answering service, not a machine, and I’d call to check the message.

“This is Malcolm,” he’d begin, in a voice that sounded like an Appalachian Keith Richards with strep throat. It’s the voice that could make Tom Waits feel like an innocent. “What are you doing? I’m calling to pick your brain.”

I was sleeping. And I didn’t want my brain picked. Still don’t. He never left a number. I never called back. But I knew who he was. I’d listened to him, a lot. I used to play his music — either on the stereo or, haltingly, on the guitar — for people. I suppose he had heard about that. I’d listen to that Steve Earle song about somebody or another being the last of the hard core troubadours, and then I’d listen to Malcolm Holcombe and I’d know Steve was wrong on that one. Then again, Steve Earle is awfully good and it’s tough to peg Holcombe as the last of anything. He’s not one for a line. He’s elliptical, obtuse, indistinct and vague, and yet somehow he hits the nail wherever it is that you’re supposed to hit the nail.

“Strong soap, and lots of hot water,” he’d sing/snarl, on an album that someone gave me, thinking (incorrectly) that maybe I could help. “Behind my ears, pound by pound/Before my eyes, one moment to moment/Pages rockin’, justice in a cradle.”

“When I first met Malcolm, he was in a one-room apartment off 12th Avenue in Nashville,” said Frosty Horton, a Grammy-nominated songwriter and producer who co-produced a brilliant Holcombe album that will probably never be released. “He was playing these songs, and I said, ‘Malcolm, man, what is ‘Justice In A Cradle’ about?’ He gave me that wolf-eyed look and said, ‘Frosty, what do you think?'”

I never knew what to think, so I just felt. And what I felt was that Malcolm Holcombe could jab a heart from a different angle. That didn’t mean I wanted to answer my phone at two in the morning, but it meant I wanted to listen to him when I re-woke up at eight or nine. Not that Holcombe’s music was easy over eggs. He was bracing, always. Malcolm Holcombe is lullaby-less. Somebody once told me he played brilliant songs that she didn’t want to hear.

He reinvents our language, this Holcombe fellow. Or he subverts it, at least.

“I’ve heard misfortune losses/And wasted ways before me by the costs,” is what he wrote. “Of givin’ someone time enough for spendin’/Love only borrowed.”

David Olney, another brilliant enigma, drove him to the 12 Oaks Motel one time in Nashville.

“That’s kind of a last stop, or at least it looked like that to me,” Olney said. “It looked like a place for people heading toward oblivion, and he had a room there. I went into the room, and he had a picture of his son, who had died. It was the saddest thing you could imagine, but it was totally real. There was nothing you could do, except have a good word for him.”

Malcolm Holcombe, 52, isn’t to be pitied, and, anymore, he’s not to be scolded. He’s to be heard, though.

“When I first caught him, I thought, ‘This is like knowing Robert Johnson. This is one of a kind. This is as good as it gets,'” Olney said. “Every image is completely organic. I think anybody who does this stuff and is not just pandering always has some feeling that they don’t quite fit in the world. Like the world’s only a size 6-and-a-half and you’re a size 7. But even of all those people, Malcolm is the one who really doesn’t fit. He’s his own brand.”

His guitar playing is completely atypical. Holcombe bangs and pounds on his acoustic, which he tunes down a whole step and then capos at the first fret, thus raising it a half step from the whole step down. It’s the musical equivalent of one step forward and two back. In his lyrics, he creates patterns of images that aren’t bound by any notion of achieving specificity of anything other than emotion. Wasted words and untruths are nonexistent.

“I have been known disappearin’ now and then,” he once sang.

He even writes truths about untruths.

“Knowin’ right, still doin’ wrong/As a hundred lies unfold.”

“Everything has something to do with the writing,” Holcombe told me on the phone one November morning. “Rain or shine, or a butter knife in the ribs, it makes a noise, don’t it?”

God, how would I know? I’ve never seen, heard or felt a butter knife to the ribs. I think Malcolm probably has. I don’t know why on earth anyone would attack anyone else with a butter knife. I can’t imagine such a storm of impotence and brutality. I think Malcolm probably can. You can hear it in his voice, if you’ve listened to his voice.

“Mother said I sang through my nose,” he said. “I just tried to carry a tune some way or another, just to pass the time.”

Malcolm Holcombe doesn’t give linear answers to direct questions. He doesn’t give direct answers to non-linear questions, either. He doesn’t like to give answers at all. Or really to ask questions, save for the occasional “Don’t it?” As in, “It makes a noise, don’t it?” or “Shit happens, don’t it?” or “She saved my life a couple of times…like everybody else on this planet, it seems like, don’t it?”

And so the notion of enlisting Malcolm’s help in writing The Malcolm Holcombe Story is inherently ridiculous. And the notion of calling up his friends, peers and associates to help fill in a timeline is inherently ridiculous. If there is an omnipotent being, then that’s the fellow or madam who can fill in the Malcolm Holcombe timeline. The rest of us glean from glimpses and fragments.

***

“We ain’t s’posed to know everything there is to know,” he sings on his new album, Gamblin’ House. Due out January 15 on Echo Mountain Records, it was produced by Ray Kennedy, the fellow who worked on Lucinda Williams’ Car Wheels On A Gravel Road and Earle’s I Feel Alright and Billy Joe Shaver’s The Earth Rolls On.

“My gut instinct says that this is going to be the album that puts Malcolm across,” Kennedy said. “If this only gets to the people, they’re going to embrace it. The songs are magical, and people are always pretty intrigued by Malcolm, ’cause he’s a bit of a character. Man, I’ve worked with loads of characters. That seems to be the world I live in. Anyway, people see the character, but what they’re really drawn in by is the emotional impact of what Malcolm sings and plays.”

Justin Earle was barely a teenager, and already something of a wanderer, when he first heard Holcombe.

“I had run away from home and was living in Johnson City, Tennessee, in a small commune of songwriters,” Earle said. “Malcolm was spoken of around there like this ghost that haunted the streets of Johnson City. That was in his ‘gone time.’ But the first time I saw him was at the Down Home in Johnson City. Scottie Melton introduced me to him as ‘Steve Earle’s son,’ and Malcolm looked at me and said, ‘Well, who gives a fuck,’ and then he walked away. I thought, ‘This is going to be horrible,’ and I was mad at Scottie for dragging me out. But then he got up, and the first song he played was ‘Dressed In White’. It was shocking to me….Back then, he had this ability to be completely out of his mind and put on amazing, back-breaking shows.”

Holcombe doesn’t figure that to be any sort of big deal.

“You’re up there and you’re looking out at either your saving grace or the lynch mob, one or the other,” he said. “People pay money and it’s hard-earned, and it’s our job to go for the throat and deliver the fucking goods.”

Holcombe was born in 1955 in Asheville, North Carolina. He lived in a place called Weaverville, in the Reems Creek Valley, less than ten miles north of Asheville. Appalachia. He had a mother and a father (a bus driver) and siblings, and he had a neighbor with an electric guitar. Malcolm would sit on a porch with that neighbor’s guitar and a Mel Bay chord book that had pictures to show him where to put his fingers.

“Once I got past the first page, the rest of it was out of my league,” he said. “Those orchestral chords, that’s too much information. I was just trying to go ahead and keep a grain of sanity. Things moving all the time, man. ‘Like sands through the hourglass.’ Did you ever watch those soap operas? Mama Holcombe watched ‘The Edge Of Night’. I watched the Flatt & Scruggs show, on WSPA, channel 7, out of Spartanburg. I guess Earl’s still alive. I don’t know. I liked that bluegrass. They had a shindig on the green, every Saturday across the bridge near Westgate in Asheville. Little groups joining in and doing bluegrass tunes. I never could play that stuff. Kept dropping my pick.”

In high school, Holcombe played in a folk group. He didn’t get to sing — the goal was Kingston Trio-type stuff, and Malcolm’s voice was, as Guy Clark wrote in “Randall Knife”, meant for darker things — but he chunked away at rhythm guitar.

When Holcombe was in his teens, his mother died. His father died when Malcolm was in his early 20s, and Holcombe entered the scuffle and fray of Asheville’s club scene. He had a band called Redwing.

“I used to play this place, Caesar’s Parlor,” he said. “It was a local saloon. Wide open. Like the Nu-Way Lounge in Spartanburg. I’m talking wide open. All your buddies, all the people that know your family, they’re in there. There’s nice folks that’ll take you under their wing and buy you some beer. Next thing you know, you’ve got bar buddies. I guess I navigated out of that bar for a few years. Then I ran into some folks passing through. I can’t remember shit from apple butter about all that. But, damn, apple butter is tasty.”

Somewhere in there, Holcombe moved to Florida with Redwing. Every now and again, Holcombe would get to play an original in that group. The west coast of Florida didn’t prove to be any fine place from which to launch a career, though, and Holcombe wound up back in Asheville. Then, somewhere in there, he teamed with a James Taylor-esque duo partner named Sam Milner, and they released an album on a local label.

And somewhere else in there, there must have been a woman, and there must have been a child. It’s not an easy deal to get Holcombe to talk about these things. The child suffered from cerebral palsy. Malcolm loved him deeply, though theirs could not have been the most normal of relationships. The late 1980s and early 1990s were filled with alcohol and misunderstandings, and probably much more.

In September 1990, though, Holcombe took a Greyhound bus to 8th Avenue in Nashville, Tennessee. Ask him about that town, and he’ll begin with a low, guttural noise that lasts a few seconds longer than maybe it should. Then he’ll say something like, “Ain’t nothing simple in this stuff. If you hang around the barber shop long enough, though, you’re gonna get clipped.”

Holcombe found work at Douglas Corner, a little room that to this day draws the kind of songwriters and audience members who would stand a good chance of being shushed out of the hallowed Bluebird Cafe a few miles away. It’s a place where good (and sometimes great) music rings against brick walls, and where songs and singers are respected but not deified. In the early 1990s, Douglas Corner also served up the third-best hamburger in the city (behind Rotier’s and Brown’s, for the record), and Malcolm Holcombe was the guy flipping the meat and cleaning the plates.

“When I first met him, he was this meek, polite guy, working there in the kitchen,” said harmonica virtuoso Jelly Roll Johnson, who has been a fairly constant presence in Holcombe’s musical life for the past fifteen years. “I didn’t know he was a songwriter. I was playing at Douglas with Tony Arata and Scott Miller [the Nashville songwriter, not the leader of Scott Miller & the Commonwealth], and they called him up to play. He took off his apron and walked up to play. When he played…he got up there and I’d never heard anything like it. It was just incredible. He did one or two, then put his apron back on and went back in the kitchen to start working again.”

***

In a town built on songs, Holcombe was offering up works that were wholly different. They carried an Appalachian soul, with the sadness and humanity of something Sara Carter might have sung, but with melodic sophistication and an entirely unusual poetic sense. In person, he could wail like a madman. Really, he could wail AS a madman. But he retained an essential control over his surroundings.

“In a town where so much is formulaic, this was someone who just didn’t care to participate in that brand of songwriting,” said Arata, an early and ardent champion of Holcombe who found his own way into the mainstream by penning Garth Brooks’ “The Dance”. “There are lines he wrote that are ingrained in my head, like, ‘There’s belonging in just longing for someone.’ And once he got to town, he started getting a lot of attention. I remember a bigwig from A&M Records coming down for a showcase, and there was no one there at Douglas. Malcolm walked onstage wearing his apron and put on one of the best sets I’ve ever heard. He did a string of songs, then walked back to work in the kitchen.”

Holcombe didn’t sign with A&M. He found his way to Geffen, signed a deal and made an album in 1996. Lucinda Williams talked about him in interviews, and he did photo shoots and radio spots. A camera crew from the Eye On People cable network followed him around, attempting to document a writer on the rise.

They wound up documenting some of his brilliance and much of his belligerence and pain, as he went on a bender and took an ill-planned, ill-executed trip back to North Carolina in a failed attempt to see his son. Sometimes, he’d show up in concert and put on shows so stunning that folks still talk about them. Sometimes, he’d show up and put on shows so stunningly incoherent that folks still talk about them. One night, he performed with Olney and sang with his back to the audience.

“When I moved here, I thought I was a rebel,” Olney told the crowd. “Now, I meet Malcolm and I feel like Vic Damone.”

Then Geffen decided not to release the album. That decision was as astonishing to folks who’d heard the album as Holcombe’s stage show could be astonishing to the uninitiated. It was, nearly unquestionably, a masterpiece. Geffen paid to record it, paid for the cover art and paid to have promo copies pressed and shipped (GEFD-A-25135, for those scoring at home). But the thing didn’t come out.

Holcombe plays down any devastation he might have felt in the aftermath of that busted chance, but it looked for all the world like a crushing blow. “It was pretty weird, very strange, and they spent all that money,” he said. “About the time the check cleared, the hatchet came down. Everybody’s got a war story, a sob story. So you pull your bootstraps up. Some friends helped me get my shit back together, and I started shining shoes again. It was a pain in the ass and a kick in the pants.”

“Shining shoes” is Holcombe’s metaphor for the minstrel life. In truth, it took him awhile to get to where he was well enough to shine again. He had signed with Geffen as an artist of significant promise, with significant backers and fans. Now, he was an artist who’d been paid to make an album that the company had decided wasn’t viable enough even to release. He was also an abuser of drugs and alcohol, and he was reeling from the death of his beloved 11-year-old son.

“I had no idea the baggage he carried around,” Arata said. “The loss of a child will send the most grounded individual into a tailspin. And if you’ve got any inclination toward abuse…”

Holcombe bore the brunt of that pain alone, and those around him saw unchecked wildness without understanding some of what was behind it. At the same time, copies of the unreleased CD were circulating around Nashville, and Holcombe began earning a reputation as something of a mad genius.

“My friend played me this record,” said Jared Tyler, who would become a friend and collaborator of Holcombe’s. “He said, ‘It’s this crazy guy. Kind of gets drunk sometimes.’ I listened and was dumbfounded. It’s the most blown away I’ve ever been by a single, long-play record. The purest, most honest tone I’d ever heard. From that point on, I was kind of obsessed. There was no cover on the CD, so I didn’t even know what he looked like.”

At the time, Tyler worked in the kitchen at the Bluebird Cafe. Holcombe played there one night, and went to hide.

“This wiry guy came into the kitchen,” Tyler said. “I thought he was off the streets or something. Somebody said, ‘This is Malcolm Holcombe.’ I was shocked, and I said, ‘What are you doing back here?’ And Malcolm said, ‘What are you doing back here?'”

Later, Tyler was onstage with Holcombe, playing dobro at some festival in Philadelphia. Holcombe played only three songs, but he tore the house down. By the end of those three songs, he’d kicked a chair off the stage, thrown down a music stand and given everything he had to get people to somehow understand just what it was that he was doing up there.

“When we left, I could feel and smell and see the blood and guts he left scattered on that stage,” Tyler said. “Most people, you’re hearing one little level of their soul. They’re not willing to bare it all.”

The Geffen album finally slipped out in 1999, filtered through Universal’s reissue imprint, Hip-O Records, under the title A Hundred Lies. David Fricke raved about it in a four-star Rolling Stone review. But it wasn’t so much released as dispersed, and it wasn’t really all that well dispersed. For his part, Holcombe was flailing, and desperate.

“Your back ain’t strong enough for burdens doublefold,” is what Townes Van Zandt wrote. “They’d crush you down, down into nothing.”

“I didn’t think Malcolm would make it out,” Justin Earle said. “I was afraid that he was going to become another one of those famous-after-death songwriters. Malcolm’s whole thing was always unpredictable. He’d disappear for a week, then come back and do something insane.”

***

What he was doing was losing his screws in public. There were moments of temporary redemption — an album recorded by Frosty Horton and Richard McLaurin is as splendidly written, sung and played as A Hundred Lies; Horton was unable to find a label and the album remains vaulted — but the early part of the new century brought mostly sorrow and uncertainty.

In Nashville, Holcombe had supporters. He had a publisher, and a hands-on administration deal at Bug Music. Horton was shopping demos and pitching Holcombe to labels, Jared Tyler and Jelly Roll Johnson were playing shows with him (often for little or no remuneration), Tony Arata stuck close by as a friend and booster. But the business deals eventually ended in acrimony. Holcombe isn’t one to rest comfortably while others control his artistic destiny, even if he’s being paid something to cede control. He wound up feeling taken advantage of, and his depression and depravities intensified.

Tyler recalls chasing him through the streets of New York, trying to get him to a gig. Another time in New York, Malcolm decided he knew who lived in an Upper East Side apartment, climbed the fire escape and scared the hell out of some stranger. Holcombe would do the back-to-the-audience thing, or play deliberately out of tune. One night, he wandered into the Station Inn, walked up to various patrons and menacingly repeated, “Cat Power!” No one knew what he was talking about. Turns out he had just been booked for a small tour, opening for the singer-songwriter who goes by the stage name Cat Power.

“I hung around town, wrote some tunes, worked at Captain D’s and did odd jobs,” he said. “Which Captain D’s? All of ’em, man. I was milking the clock, trying to stay busy. Went around the block with some drugs and alcohol, like any other idiot. And then I pulled out of town. You pay the piper and walk backwards.”

Whether by grace or will or dumb luck — maybe all of them — Holcombe wound up disproving Thomas Wolfe, returning home to North Carolina and making it work. He found a girlfriend, then got married. And he got clean. It couldn’t have been as effortless in the living as it is in the telling.

“I ended up meeting a lady and falling in love,” he said. “Drilled a hole out here in Swannanoa. We decided to…aah, to pool our resources. Even put out a couple of indie albums. And, damn straight, it was different this time. Matter of figuring out some roadblocks and potholes now and then. My wife’s been a big inspiration, you know? And you’re as good as the company you keep. Ain’t no man an island.”

And then the subject is closed, at least until I listen to Holcombe’s new Gamblin’ House album, on which he sings, “Cynthia Margaret is an angel of mine.” Nothing cryptic about that.

In 2005, Holcombe self-released I Never Heard You Knockin’, a guitar/vocal album of considerable charm, wisdom and introspection. “This town knows me lyin’ on my face/Broken gutters and cussin’ the rain,” is one passage. And on a song that many hear as being about his mother, it’s “I cover my ears to the pain of you leaving me behind.”

He followed that with 2006’s Not Forgotten, a sometimes lovely, sometimes harrowing ensemble piece reminiscent of the unreleased Horton/McLaurin-produced album. He had also established a habit and reputation for showing up for gigs and singing what was on his mind, not what was out of his mind. Malcolm Holcombe was still an enigma, but no longer a hazard and no longer a ghost.

“He’s still Malcolm, and still extremely unpredictable,” Justin Earle said. “You never know what he’s going to say or do, but every show he does now is great, and his unpredictability isn’t going to hurt anybody anymore. You don’t have to worry about him climbing people’s fire escapes.”

Tyler, Arata and Jelly Roll Johnson figure Holcombe is, maybe for the first time, comfortable in his own skin. That doesn’t make him benign. He’s still angry as all hell, it’s just that his rage isn’t scattershot. Much of Gamblin’ House finds him moving beyond internal excavation and into the emotional ramifications of living in the present day. He figures the government’s executive branch is gambling with people’s lives, overseas and domestically. And he figures he’s seen the faces of those who’ve been lost in the gamble.

“There’s things to think about,” Holcombe said. “We’ve got another year of Bush, for one thing. Sheep off a cliff, that gets old. And I’m tired of landing on my head. I can jump off the cliff myself, and I have one time or two. But when you get people helping you, like some good old attorneys in fucking Nashville, or our president…you get enough stuff like that, and there’s going to be a revolt.”

To record Gamblin’ House, Ray Kennedy gathered bassist Dave Roe, percussionist Kenny Malone and multi-instrumentalist Ed Snodderly around Holcombe in Asheville, North Carolina, and spent a few days recording tracks and vocals. Then it was back to Nashville, to add some flourishes and mix the thing. Easy enough, then, and all involved are using words such as “magical.” They recorded more than they’d expected to get, which accounted for the release of the Wager EP in late 2007. The full album is being released on Echo Mountain, an up-and-coming North Carolina-based label that needs Holcombe as much as he needs it.

“I’m prayin’ for a home I can believe in,” is how the album ends. “Prayin’ for a home I can call mine.”

Malcolm Holcombe figures he’ll tour through the year and beyond, supporting Gamblin’ House, railing and howling against the new McCarthyism and the old demons, and railing and howling in favor of open-heartedness, empathy and things such as that.

“I try not to be too mealy-mouthed and mushy,” he said, talking on the phone in the late morning. “Try not to let the bubblegum replace the nail in my foot. The pen is mightier than the sword. That’s pertinent to me. Whoever said that, though, they’re probably dead.”

It was then that it seemed pertinent to ask Holcombe whether he really believed that, about the pen being mightier. It’s a hard thing to believe, what with beautiful songs being written and sung every day while bodies break all over the world. I asked him about that because I wanted to see if that’s what he really thought. I asked him that because I wanted to pick his brain.

“Believe it?” he spat. “That’s what I said. Shitfire.”

Peter Cooper writes and lives in East Nashville, Tennessee.