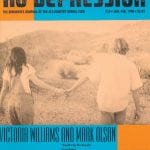

Victoria Williams – Desert Bloom

And while we spoke of many things,

Fools and kings,

This he said to me:

The greatest thing you’ll ever learn

Is just to love and be loved in return.

— “Nature Boy”, Victoria Williams

The Original Harmony Ridge Creek Dippers live simply in a refurbished late-1950s cabin, tucked amid the high desert and surrounded by sand and sky, hearty herbs and huge, shy, loving dogs.

Mark Olson is in the kitchen, heating an early November lunch of leftover turkey, fresh-plucked arugula salad and squaw tea. Victoria Williams is in the bathroom, taking a quick bath before an afternoon encounter with the camera.

Out on the front porch an ex-Navy sonar man named Dave Royer is converting surplus ammo boxes into preamps for his handmade studio microphones, and one of the three dogs is sprawled the length of a shady couch. Royer is sundried, shirtless, more skittish than the dogs of strangers.

A recording console is cloaked and tucked into one corner of the living room, next to the stone hearth Mark and Victoria built, on the other side of the small concrete fault — a reminder of frequent earthquakes — which separates that room from the kitchen and the small, four-burner electric stove Victoria found in a junk shop. An upright piano next to the front door is the only instrument visible.

Born here, then, are the songs of Victoria’s latest Atlantic release, Musings Of A Creek Dipper (due in stores Jan. 13), and the full flowering of Mark’s first post-Jayhawks outing, The Original Harmony Ridge Creek Dippers (available only from his P.O. box here in the California desert town of Joshua Tree). And if it sounds like Victoria sang her parts in the kitchen while doing dishes, she probably was.

Highway 10 east from Los Angeles, that long drive Hunter S. Thompson roared across 25 years ago toward the ruination of fame and the gaudy conflagration of Las Vegas, forks a few miles past the last outlet mall just before darting through the unflinching Mojave. A well-tended spur to the right winds into Palm Springs, where the streets are enclosed by lavishly irrigated lawns and named for prominent Republicans. To the left, rising toward the high desert where wind and rock and patient Joshua trees remind of a peace and endurance that politics can never fashion, up that road, not far from where Gram Parsons’ ashes were once spread, is where Victoria and Mark live.

Damp-haired Victoria offers a short prayer before lunch, a reminder to their secular guest that religion need not be a caricature of itself. She speaks and laughs and sings in such a way that her surroundings are decorated with exquisite grace. Though she is 38 now, Victoria’s voice, her eyes, her smile, they all retain a gloriously childlike charm. She sings high and sometimes uncertain (“wobbly,” she’s called it) in a register that links her to occasional duet partner Julie Miller; mostly, though, it’s an exceptional mix of innocence and wisdom that radiates through her songs: Peace.

Those sounds, and the spirit behind them, are Victoria Williams’ blessing. It is a small curse that she is still, perhaps, better known for having multiple sclerosis, the disease she has battled since 1992, than for the rare joy of her songs.

Victoria Williams was 19 when she came to Los Angeles in the early ’80s, a hippie chick from Shreveport, Louisiana, probably a wild child — striking enough a weed even then that Mark well remembers watching her open for punk rock bands, just a gal and that voice and her guitar. She was married to somebody else part of that time (singer-songwriter Peter Case), but things have a way of working out.

“The not shady part of Victoria’s past,” Mark says with a warm glance, gently cutting her off before she reveals too much about leaving Louisiana to the tape recorder, “is that she learned…she has a unique rhythm style. She can play many different instruments, and she learned that in Louisiana, playing with a lot of different people. When I first saw her, that’s one of the things that I just went, ‘Wow, she can really play rhythm guitar, lead guitar, piano, in her own style, that kind of harks back to that part of the country.’ On this Creek Dippers thing, I’ve always wanted her to be playing, not just singing, and that’s why we did it that way, just her, Mike [Russell], and me.”

The name that connects their two albums links Victoria to Mark as well. “I was out opening for the Jayhawks years ago,” Victoria says. “Mark left the tour bus and rode with us and we’d go creek dipping every day. We came to this one place, it was called Harmony Ridge, and we creek dipped there.” (They also adopted a revised version of the name, Rollin’ Creek Dippers, for a European tour last year with Buddy and Julie Miller and Jim Lauderdale.)

Victoria was touring with Neil Young in 1992 when her hands became unexpectedly reluctant partners in the playing of her guitar and piano. A handful of doctors later, she had that unhappy diagnosis — MS is a non-lethal disease that attacks the body’s immune system and damages the myelin sheath which surrounds nerves in the brain and spinal cord — and $20,000 in unpaid medical bills.

At the time, Victoria had no record label. 1987’s Happy Come Home began and ended a relationship with Geffen; 1990’s Swing the Statue! appeared on the ill-fated Rough Trade, a label/distributor whose bankruptcy all but destroyed indie rock that season. The response to her plight by friends and fellow artists sparked creation of the Sweet Relief organization.