Toasting to the Blues and Rap

I admit straight away that, while the blues touch my deepest emotions, rap music does not strike a chord in me. Having reached the age where retirement is no longer an abstract notion, I can hide behind the (cheap, and probably invalid) excuse of a generational argument to justify my lack of interest too in this primary ingredient of hip-hop culture. It offers some comfort to know that I am not alone in this differential liking and interest. A 2008 study exploiting data on the co-occurrence of artists and genres in playlists shared by members of a popular web-based community, demonstrated that when one loves the blues, one generally also like jazz music. However, while rhythm-and-blues and rap music commonly share playlists, a high affinity for the blues seems to go hand in hand with a low affinity for rap music (Baccigalupo, Plaza, Donaldson).

Yet, rap music and the blues have much in common. Obviously, all classification effort hurts the complexity of reality, but there are arguments to see rap music, next to the blues, jazz and rhythm-and-blues as one of the four major musical, expressive forms of black culture. They all share the same bedrock of a black consciousness, which developed in a dynamic and creative way in relation to a European inspired New World. It is in the basic features of the Afro-American culture that we need to look for common traits of the blues and rap that go beyond the sole observation that both genres stemmed from the frustration of a discriminated populace forced to live in the underbelly of society.

Not everybody will agree to this pedigree, and it is not too hard to find students who emphasize the different historical lines that separate the two musical genres. American academic, Ferenc Szasz for instance, argues that rap does not come from Africa, but from the medieval Scottish pubs where the Caledonian art of “flyting“, a word battle, flourished. He contends that Scottish slave owners – he forgets to mention that there were also Scottish slaves – took the tradition with them to America, where it was adopted and developed by slaves, emerging many years later as rap. I have no intention, however, to polemic on this roots issue, my only aim here being to highlight one common denominator in the blues and rap: the power of the word.

THE BLUES IS MORE THAN TIN PAN ALLEY

My first meeting with the blues has been the goose bumps hearing the guitar work of artists such as Eric Clapton, Buddy Guy, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Gary Moore. I equated blues with a mastery of the guitar strings, bringing out the deepest feelings of sorrow and melancholy. Stevie Ray Vaughan’s ‘Tin Pan Alley’ cut me to the bones. It is only later that I discovered that the blues are in the first place a vocal art, where an instrument such as the guitar is in the literal sense of the word, the ‘instrument’, the ‘tool’ that serves the lyrics and the voice. The blues are, as Small expresses it, an art form where the human voice is always paramount: “the paradigm of blues sound is vocal, even when it is transferred to instruments” (p. 204). Ruben et al. qualify some female blues singers as Bessie Smith as having had a seminal influence on the very conception of vocal art in the 20th century. LeRoi Jones contends that “blues is not, nor was it ever meant to be, a strictly social phenomenon, but is primarily a verse form and secondarily a way of making music” (p. 50) When one considers the early blues as a solo-act, an individual performance that stood on the bolstered ethos of individualism at the end of the 19th century, one can trace the ancestor of the blues in the first place to the field hollers, the chants and shouts of the individual slave mourning alone on the field. What primed was the sound of the voice, “the rising and falling and breaking into falsetto”. Replacing in an early stage already the banjo, the guitar was added to accompany the soloist “songster” in a call-and-response structured song. The goal of his guitar was to emulate his voice and his improvisatory style. What attracted me in the first place in the great guitar work of my first blues heroes was probably the vocal-like approach to their penetrating solos.

What distinguishes rap music in addition to its stylized and strong, repetitive beat, is the use of spoken vocals, using a poetic device such as rhyme. Rap is chiefly a vocal performance against a musical backdrop. It is through his “voice of authority” (M.T. Carroll) that the successful rapper (“Master of Ceremony”) creates a bond with his audience, that he provides his listeners with an experience of identity. Textbooks on “How to rap” detail guide lines on how to use the voice to perform, how to “flow” (play with rhythm and rhyme). These books stress the importance too of the content. As American rapper Lord Jamar, aka Lorenzo Dechalus formulates it: “at the end of the day, subject matter is the thing that would really be the meat of what” a rapper is doing. Rapping is spoken word poetry performed in time to a strong beat. I remember having read somewhere that rap is “poetry on steroids”.

The content of the song matters to both blues and rap, and they run quite a stretch along parallel lanes. The blues performer shares through his song his experience of reality with his audience which can readily identify itself with this common experience. They share “the truth”, the non-romanticized, plain reality of everyday life, in all its painful and joyful moments. The rapper’s lyrics are equally “realistic”, dealing with sex, love, violence, gender roles, politics, race, partying, money, comedy/parody and boasting (J.C. Lena). The lyrics, which are often an expression of his own real-life experience, are a paramount part of the identity of the rapper. In its content, rap is an oppositional culture that offers a message of resistance, empowerment, and social commentary. Both blues and rap reflect, in their original form, a merge of the performer, his song and his audience. Both share, directly or indirectly, in a large degree the theme of white supremacy.

In their form, the blues and rap differ however on at least the aspect of the economy of words. The blues excel in using a language rich of imagery with verses that, at first sight, do not look coherent but that at closer inspection are clearly linked together in the communication of a strong personal feeling. Contrary to rap music, the blues seem more concise, and economical in their use of words. They bear strong family ties to black poetry, young poets in the Harlem Renaissance claiming even that the blues were a part of their poetic heritage. It is impossible to read Langston Hughes without listening at the same time to the early blues. When I listen to rap, however, I feel quickly overwhelmed by the flow of words. It is as if the syllables come out in a waterfall of words, in a “flow” picturing an artist who becomes hypnotized. Rap is also poetry, but it is less word frugal, firing of the lyrics.

What characterizes both, however, is the strength of the word.

A BABY IS BORN WHEN YOU NAME IT

The word ‘word‘ is a key element to the understanding of blues and rap, and to black music and culture in general. But for a good comprehension of its significance we need to put aside its European definition, and turn to the African concept of “nommo” (1) which in turn cannot be interpreted without locating it in its broader cultural context.

The traditional African culture envisions the cosmos as a whole, composed of the gods, the spirits (of ancestors), the human beings, the plants and animals, and finally the inanimate objects (the “things”). All these items are in balance, mutually inclusive, and interacting to build the universal cosmos of life. There is a fundamental unity between all the material and spiritual, immaterial aspects of life. The secular and sacred, life and death, night and day, black and white…they are not regarded as opposites, but as part of constant and continuing forces. However, none of those forces (not even human beings) can be activated by itself. They are dormant, non-active until something awakens them. This “something” is “nommo”, the word. The “nommo” is the water, the seed, the blood that has the capacity to bring life to the different components of the universe. “Nommo” is the necessary juice of life.

Only the human beings (called “muntu”) have the ownership of the “nommo”. The “muntu” possess the exclusive property of the magic, and dispose of the power of the “nommo” to give life and efficacy to all things in the cosmos. “Nommo” brings things, ideas, and concepts into existence; it is the absolute, indispensable condition for procreation. Even a newborn child can only become a “muntu” when the father, or a sorcerer gives the child a name and pronounces it. The spoken word, the naming, breathes life into the child. Its very existence as part of the cosmos, as a “muntu”, comes solely from the speaking of the child’s name. Should a child die before its name is pronounced, it would not be mourned. It is thus not by the act of birth that a “muntu” comes to life, but by the word-seed. It has to be designated as a human being by the force of “nommo”. The same principle goes for instance for the plants and crops. Through the “nommo”, expressed in dances, the “muntu” give life to the seeds: a plant grows only by the power flowing from the word.

Hence, in African philosophy, a human being has by the force of his word, dominion and power over “things”, which he can change, make work for him and command. It is also the force by which all elements of the cosmos can be organised. Contrary to the European definition, the ‘word’ is far more than just a part of a communicative act: the spirituality of the communication itself is crucial. The word is able to manipulate all forms of initially raw life and transform them; it has an energy on its own, capable of conjuring up spirits, dreams, life itself. As such, it stands independent from the “speaker”, who becomes only the vehicle of the word. A word can bring power with it, unlike the European philosophy where the speaker grants power to the word. In African philosophy “word” is made part of the human will. It also forces the listener to look further than the literal meaning of a word, but rather to have an eye for the power it generates and its results.

Ruch and Anyanwu (1981), when discussing African philosophy, describe the distinctiveness of the latter in relation to the Western, Christian view of the world, as follows:

“The Christian is proclaiming and testifying to the word of God. The African does more than that. He possesses the power of word and this power unceasingly transforms, transmutes, creates, recreates and procreates things and even God. Word alters the world.”

HARMONY THROUGH TONE, VOLUME AND RHYTHM

Molefi Kete Asante, an African-American historian, philosopher, and leading scholar in the fields of African American studies, builds further upon the concept of “nommo”, and identifies six of its essential features, which will sound very familiar when you keep in mind the characteristics of blues and rap:

- First, “nommo” emphasizes the creative genius and power of the speaker, of the artist. The spoken word is considered as a powerful, creative attitude, rather than an object.

- Second, “nommo” is an essential collective concept, referring to communal activities. It has no meaning for an isolated individual. The African discourse eschews the distinction between the speaker and the audience. Performing the “nommo” is a mutually empowering event. It is able to create a sense of shared experience and communal feeling, that is at the same time motivating each other’s actions.

- Third, “nommo” organizes the cosmos, brings harmony, restores stability in a troubled world. The key factors in the vocal delivery are the tone, volume and rhythm of the discourse.

- Fourth, as said above already, “nommo” is all about bringing “things” to existence through “naming“, “speaking” their name.

- Fifth, “nommo” is intrinsically linked to a view of reality as a “whole”, where there is no distinction between the secular and the sacred, and where the everyday life is a micro-cosmos of the larger universe. The word reveals life.

- Sixth, and finally, in resisting chaos and by bringing order, “nommo” is a source of liberation and celebration, creating new spaces in which freedom of expression can grow.

Other authors added another intrinsic aspect of “nommo”: humor in the form of ridicule, mockery and wit (Janheinz Jahn, Ruth Finnegan, Deborah G. Plant).

Language and sound being the very heart of the “nommo”, and of the African culture, are thus much more than instruments of communication or music. Because tonality, volume and rhythm are the basic features through which the word can deploy its creative power, the use of language and sound is in its very essence a “spiritual” event. In a Western-European view, we label its expression as “music”; in an African view, however, it is a way to move the spirit, to bring order in the chaos. Language, speech, “music” are all part of the daily, communal life which is in itself an aspect of the whole universe.

THE WORD ARRIVED IN THE NEW WORLD

After the Middle Passage, and the arrival of the slaves on the American continent, the spoken word remained the primary means by which Africans maintained and strengthened the relationship between the different components in their environment. The belief in the power of the word continued to be strong, manifesting itself, for instance, in the conviction that all craftsmanship should be accompanied by speech (Smitherman, 1986). As in the African homeland, the art of vocal expression dominated the black communication culture in the New World. Africans in the New World kept an expressive sense that showed itself as life force in not only speech, but also in rituals, dance, music, the narration of myths, folk stories, preacher’s sermons and the telling of jokes. The evolution of the African-American culture can simply not be studied without taking into account the essential role of the life-giving force of the “word”. It is an inextricable element of Black community life. As phrased by Harrison (1972), an American playwright and professor who coined the term “Nommo” in relation to Black Theatre:

“Polyrhythmic sounds, call and response, hand-clapping, chorus, testifying, bearing witness, and vocal drum emissions are all means employed by black people on the block to conjure up the effective Nommo that intensifies communication: meaning is established when the verbal mode is harmonized.”

The power of the word united. Despite their culturally different backgrounds in their homeland, Africans in the New World recognized in the paramount place of the “word” a common denominator that helped them in the process of transforming their African culture into an Afro-American culture. The narrow space of the plantation and slave quarters was the primary environment where this power could further flourish through the maintenance, reinforcement, and the continuation of African-derived practices such as in music making, oral narratives, and belief systems (Cheryl L. Keyes, 2004). The spoken word was the building block of the Afro-American communication system that developed as an exponent of the will of the slaves to construct a (new) identity based on self-recognition, that could survive the oppressive system of bondage. Hence, the language was not only a medium of communication, it was also a way of presenting oneself: it was verbal artistry and a vehicle for commenting on life’s circumstances. “In effect the slave was a poet and his language was poetic” (Baber, 1987). This “poetic” strength blossomed in the art of preaching and sermonizing, in the field hollers, work songs and spirituals.

The verbal artistry was nourished by the need for a system that permitted slaves to share encoded messages, not understood by the white slave owner. Because they came from diverse cultural backgrounds with different languages, and because the use of their mother tongue was strongly discouraged, often even forbidden, slaves developed a language of their own that contained words with a meaning putting the white on the wrong foot. In this way, language was both a community building factor and a medium to pass communications functional in the survival of the daily hardship.

But its use went even further. Just as the cakewalk originated as a parody on the fancy white dancing style, without whites even realising the mockery, so did the black vocabulary acquire a double meaning containing comment and critic, insinuation, innuendo, implication… The word was turned against the slave holder but was understood only by the slaves. The slave owner was often, unknowingly, made the subject of verbal mockery.

After all, it was normal that Africans imported as slaves would be suspicious of a language that gave them the status of chattel property, less than human. Learning the language of the master would entail internalization of his values, accepting on the surface, at the very least, the notion of white superiority. Therefore, slaves resisted this literal process of cultural self-destruction by developing for themselves a different version of the new tongue, a version that “slipped the yoke and turned the joke back upon those who would destroy them“.

Let me, at this point, introduce the concept of “signifyin(g)” (2) , which may not be unique for Afro-American culture, but which is nevertheless a cornerstone of black culture, and of oral tradition. It goes far beyond the scope of this essay to unravel the complexity behind the act of “signifyin(g)”, which is moreover subject to major terminological confusion because the term is often used on the same level as “boasting”, “loud-talking”, “testifying”, “calling out”, “sounding”, “toasting”, and “playing the dozens”. The problem of definition is, as Onwuchekwa Jemie observes, not surprising given the fluidity and dynamism proper to an oral culture. Variations over time and in place in the terminology are very natural, and make an unequivocal definition impossible. All these rhetorical forms are strongly interwoven, and are rarely found in a pure form.

In general terms, however, “signifyin(g)” can be described as a figurative and implicative way of speaking. It is the act of using secret or double meanings of words to either communicate multiple meanings to different audiences, or to trick them. Hence, it requires on the part of the listener the knowledge of appropriate ways of interpretation and understanding. Signifyin(g) is, in other words, a kind of coded language understandable only for those who share the same culture, and therefore need decoding in order to be correctly understood. The key element is the indirect way of working through metaphor, trope and simile. Someone, I forgot his name, once called it an expressive poker.

The verbal technique of signifyin(g) is based on the shifting and redefinition of the meaning of words. Signifyin(g) operates on the difference between the explicit and figurative meanings of words. Therefore, the act of signifying highlights that words cannot be trusted, that even the most literal vocal expression allows room for interpretation. The meaning of words is not stable but variable, depending upon the context and the speaker.

Consider the example of a slave singing a work song, where the term “captain” may be used to indicate discontent about the overseer of the work, while the latter thinks the slave uses the word as a matter of respect. To cite another one: A slave who sang “Steal away to Jesus” announced in fact to his fellows that a religious meeting was organized, a message that completely bypassed the attention of the plantation holder.

YO MAMA SO OLD, HER MEMORY IS IN BLACK AND WHITE

A specific category of “signifyin(g)” is “playing the dozens“, or if obscenities are uttered, “playing the dirty dozens.” As a verbal game, a duel, it consists of a ritualized, improvised use of language that aims to put down the opponent. Just as with signifying, “playing the dozens” requires high skill in speech, verbal dexterity, quick thinking, wit and mental toughness (Carlos D. Morrison). Words are used as weapons in a battle that ends with a winner who succeeds in putting down the opponent with humorous insults. The “dozens” mainly handle the themes of poverty, ugliness, stupidity and promiscuity. Most often, “playing the dozens” focuses on the relative of whom the speaker addresses, but indirectly aims the insult at the hearer rather than his/her relative. “Momma” is undoubtedly the most “popular” character on the stage of “the dozens”. The word “momma” is the African American vernacular for “mama”, that in the African tradition also covers the non-biological parent, making the insult against a “momma” particularly hurtful and powerful.

Etymologically, the word “dozen” is sometimes connected with the 19th century practice in slave blocks in New Orleans where enslaved Africans with deformities or disfigurement were cheaply sold by the dozens. Hence, to be sold to a slave trader as part of a dozen was strongly degrading. H.L. Gates links the word to the 18th century meaning of the verb “dozen”, meaning to stun, stupefy, or to daze.

“Playing the Dozens” is not merely a game of fun. Though it can be, and most often is, a form of entertainment, it is too a battle for respect where the opponents have to exhibit emotional strength and verbal agility. It is a confrontation of wits instead of fists, a war of words.

“Yo momma” insults and counter insults are abundant. Let me quote just a few to give you a flavour of them: ” Yo momma so ugly when she joined an ugly contest, they said “Sorry, No Professionals.”, or “Yo momma so fat, when she turns around, people give her a welcome back party.” The dozens could, and often did, contain pure sexual references.

In any case, signifyin(g) and playing the dozens demanded that the players master control over the “nommo”, the generative power of the word to outwit an opponent (Carlos D. Morrison). It is at the same time a marker for the cultural identity of the speaker and the listener, for the messages can only be understood from within their own culture, not by outsiders.

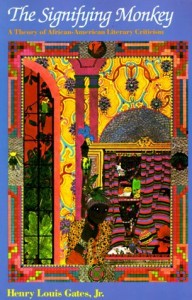

Rooted in the tradition of signifyin(g) and playing the dozens, the “toast” is another major form of African-American oral poetry, more typical however for the modern urban environment. A “toast” is a more lengthy, recited narrative or poem that, often in a theatrical manner, describes the exploits of a central character, a hero most of the time, who is willing to accept death in the face of danger. The hero is a hard and/or clever man (or animal) who has the amorality of a trickster. “The Signifying Monkey” is one of the best-known toasts. Though many closely related versions circulated, the story generally deals with a jungle trickster who by witty word play – signifying – sends his arch foe, Lion, off to be stomped and mangled by the invincible Elephant. The Monkey uses cunning and cleverness to accomplish what he cannot accomplish with physical strength. He uses verbal judo in exploiting his enemy’s own excessive ego against him, and he does it all with words.

THE SPIRIT CANNOT DESCEND WITHOUT SONG

The dozens and the toasts are commonly quoted as the inspiring structural models for rap music. In a 2010 Financial Times article (November 5th), Henry Louis Gates, Jr. calls signifying the grandparent of rap, and rap is in his view the signifying in a post modern way. While “my father and his friends called their raps “signifying” or “playing the Dozens“, Henry Louis Gates Jr. continues, “a younger generation named them “Toasts”, and an even younger generation called it “rapping“”.

The statement could be taken a level higher: black singing is practising the power of the word. Therefore, with the concepts of “nommo”, “signifying”, “playing the dozens” and “toasting” in mind, let us now come back to the initial observation at the outset of this essay, and look at some of the genes shared by the close relatives blues and rap as two forms of black singing.

An African proverb states that the spirit cannot descend without song. The song is embedded in the word, in the everyday speech and it is difficult to make a distinction between the word and the song. According to Dr. Benjamin C. Wilson, professor of black Americana studies, the rhythm and music of African American speech is evident throughout African American life, “from the ditties spun by boxer Muhammad Ali to the double-Dutch jump rope songs of children in an inner city school yard”. “When most African Americans talk, it sounds like they’re singing”, Wilson says. Music is very much a part of the African cultural experience and that is transferred to the daily dialogue, whether it is through ebonics or through the rhythms of speech patterns associated with dance music. (3) Indeed, the African-American speech itself incorporates several structural elements of what we call “music”: pitch, timbre, timing. In African language, words will bear different meanings if they are pronounced in another pitch, timbre or in different timing. African music is derived from language (Chernoff). Without African languages, African music, and by deduction, Afro-American music as blues and rap would simply not exist (Victor Kofi Agawu). The blues and rap are language derived musical forms that can, and most often are, accompanied by instruments, but that do not exist in a pure instrumental form. The song and its words hold the key to understanding both the blues and rap.

These songs testify to the reality, to the “truth”. In the words of J.D. Short: “There’s so many true words in the blues, of things that have happened to so many people, and that’s why it makes the feeling in the blues.” Or, as Paul Oliver has formulated it : “It is a peculiar feature of the blues that its subjective approach did not manifest itself in over-romanticism. Above all the blues singer was a realist, intimately concerned with his subjects but having no illusions about them: neither carried away with sentiment nor totally insensible and devoid of feeling; he was not repulsed by the uglier side of the world in which he lived but accepted the bad with the good.” Rube Lacy contended that both his preaching and his blues singing were all about the ‘truth’. Hence, in the same way as the “nommo”, the word was an integral aspect of the daily life, so is the blues and rap song a testimony of the reality in which the performer lives. They don’t bring a witness of some imaginary world, but tackle the reality in the universal human experience. No more than the blues is rap about a make-belief world. As a rap performer put it: “When I’m rapping, either I’ve been through it, or I have seen it. I rap the truth” (4). Blues and rap are exponents of the same concerns; they are about the way the African-American shapes his identity in a white dominated society; how he wants the world to see them.

BLUES AND RAP UNVEIL TRUTH BY ITS SIGNIFIED VEILING

At face value, it seems a contradiction. Though both the blues and rap have reality and “truth” as their major theme, their lyrics seem to veil and deny reality by covering it up in a highly metaphorical and figurative language. However, it is precisely in this creative, metaphorical approach of the world that not only they posit themselves in the long black cultural tradition of signifyin(g), but also succeed in making reality more poignant, yes often even feel more painful. Simultaneously, by the use of signifying as a major rhetorical device, the blues and rap function as markers for cultural specificity because the listener needs to understand the culture within which the lyrics and metaphors are used in order to grasp the true meaning of the message.

Perhaps nobody has formulated the importance of signifyin’ in the narrative of the blues lyrics better than Memphis Slim:

“Blues is a kind of revenge. You know you wanta say something…you wanta signifyin’ like – that’s the blues. We all fellers, we had a hard time in life an’ like that, and things we couldn’t say or do we sign it, I mean we sing … So it give him the blues, and he can’t speak his mind. So he made a song of it, he sang it. Still, he was signifying and getting his revenge through song.”

If you can’t say it, sing it, but in a way that you say one thing, but mean another. The blues lyrics are then a song of allusion, of indirection, an implicative and figurative speech, an expression of double-voicedness. The meaning of existing words is (constantly) redefined in order to fit the changing social, economic and cultural context in which the African-American finds himself marginalized in ever new forms.

The blues’ metaphorical imagery pertains to different aspects of the black environment. In some cases, the signifying is used not only to simply comment on social conditions, but also to protest against it. The social criticism was for instance clear for the black audience when Jimmy Reed sang in his “Big Boss man”:

“Big boss man

Can you hear me when I call

Oh, you ain‘t so big

You‘re just tall, that‘s all“

The recurrent blues theme of the interpersonal relation between the genders can also be seen as a metaphor for the freedom that African-Americans were denied while in bondage. The trouble that speaks so often from the blues songs can be a figurative speech for social problems. The desire to find a good man or woman was too a symbol for the desire to create a life free of poverty, discrimination, and all other causes of blues.The hidden meaning behind the sexual language in the blues pictured a desire for social freedom.

Furthermore, when an artist sang about the blues, he often did not point to concrete causes of misery. The word “blues” acted as “nommo”, used to designate, “signify” various situations which could cause the blues. The word “blues” conjures up diverse sources of misery, and at the same time uses the power of the word to gain control over the situation (Molefi K. Asante). It is a an expression of the need to transform the conditions that are at the heart of the blues. It is in this way that we can interpret for instance Ma Rainey’s “Blues Oh Blues“:

“Oh blues, oh blues, oh blues, oh blues, blues, oh blues

I’m so blue, so blue, oh mama don’t know what to do.

Oh blues, I’m blue, oh blues.”

The often tense relation between the blues and the black church was a highly frequent theme subject to signifyin(g). A prominent example is Bessie Smith’s song “Preaching the blues”, which title can in itself be seen as a signification upon the relation between the blues and the church, by placing the blues in a context where it does not belong, and generally is not wanted. As Marvin M. Ellison points out, Bessie Smith reveals in the song the church’s naive view of the so-called saved ones and the hypocrisy of the scorn the church shows for the blues and the blues singers. The theme was prominent in many other songs by the early female blues singers such as Ida Cox and Ma Rainey who, through sexual allusions, signified upon the church’s position related to sexuality and its failure to recognize and see the power in blacks’ identities as sexual beings.

The sexual theme in general, independent from church, was a popular subject for “double voicedness”. Innuendo permitted the blues singer to tackle subjects considered too delicate by the Victorian and Christian ideology for unveiled handling. Slim Harpo’s “I’m a King Bee” is just one example:

“Well I’m a king bee, buzzing around your hive

Well I can make honey baby, let me come inside

I’m young and able to buzz all night long

Well when you hear me buzzin’ baby, some stinging is going on”

Bessie Smith’s “Empty Bed Blues” speaks the same language:

“He came home one evening with his spirit way up high

What he had to give me, make me wring my hands and cry

He give me a lesson that I never had before

When he got to teachin’ me, from my elbow down was sore

He boiled my first cabbage and he made it awful hot

When he put in the bacon, it overflowed the pot

When you git good lovin’, never go and spread the news

Yes, he’ll double-cross you, and leave you with them empty bed blues”

Such examples can be multiplied almost endlessly. The popularity of the “hokum” songs paved also the way for the “dozens” songs as recorded boogie-woogie when, in 1929, Speckled Red cleaned up the lyrics of an existing “dirty dozen” song (E. Wald) (5). The recording was followed by similar versions by Leroy Carr, Tampa Red and Kokomo Arnold, amongst others. The dozens-based songs, as one form of signifyin’, circulated already during the preceding decades, and were ornated with lyrics that left very little to imagination. Their “natural” environment being the brothel, there was no need to “clean” up the lyrics. The following excerpt from the non recorded version of Red’s “The Dirty Dozen” gives an idea (quoted from Paul Oliver’s Screening the blues):

“Your mam’ she’ s out on the street catchin’ dick, dick, dick.

Fucked your mammy, fucked your sister too,

Would’ve fucked your daddy but the sonofabitch flew,

Your pa wants a wash, your mother turns tricks,

Your sister loves to fuck and your brother sucks dick,

He’s a suckin’ motherfucker, cocksucker,…”

Who says that contemporary rap lyrics are often soaked with obscenities?

Anyhow, rap music builds further on black oral tradition and relies heavily on “playing the dozen”, “toasting”, and in general “signifying”.

Doubtlessly, the most obvious form of black discourse in rap is the use of the “dozens”. The first academic interest in “the dozens” goes back to John Dollard’s study in 1939. He called “playing the dozens” a valve for aggression in a depressed group, a mechanism for channelling inwards and neutralizing black aggression against whites, whose racism and economic repression are responsible for the high level of frustration among blacks” (291). H. Rap Brown, one of the leaders of the younger militants of the Black Power Movement, has called the dozens a mean game because its obvious goal is to totally destroy somebody else with words…”to get a dude so mad that he’d cry or get mad enough to fight.”

Rap, however, uses more than the specific “dozens” technique. Adam Bradley unambiguously declares that signifying in general is far from dead, but continues to be alive and well in rap music. In her ground-breaking book on the emergence of hip-hop culture, ” Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America” (1995), professor Tricia Rose qualifies the use of “toasting” and “signifying” as vitally important for rap music. In 1997, Mark Costella and David Foster Wallace named their study on rap and its position as vital force in American culture adequately: “Signifying rappers: rap and race in urban present“. Signifying is a main rhetorical rap strategy, drawing our attention, as in many blues lyrics, to the gap between the literal meaning of the words and meaning attached to it by the performer and his audience.

The linguist Geneva Smitherman (1977) also identifies signification as one of the modes of black discourse employed by the rapper. She stresses with other scholars that in the rap speech the dictionary-literal meaning of the uttered words needs to be ignored. The shared knowledge between the rapper and his/her audience is essential for an interpretation of the lyrics. The rapper’s artistic talent is even judged by the cleverness he uses in directing the attention of the audience to this shared knowledge. The use of metaphor is one of the stylistic characteristics of the rappers act of signifying’, which takes the form of double-entendre, where the meaning of the word is often hidden and two-fold. The complexity of meaning and intention invites the listener to look beyond the often provocative and obscene, and not seldom pornographic, lyrics to detect the humour, joy and parody in it that can help us in unveiling what rappers really want to say (H.L. Gates Jr., 2010).

On a general level, it is by the way an interesting thought to consider rap music in itself a form of signification, i.e. of recreation, synthesis and regeneration of older black musical styles in a new form. Did the genre not evolve originally in 1970′s with the mixing of pre-recorded hits alternately on two turntables? Is this mixing, or sampling not a method to integrate earlier music into new songs, reshaping the original into something new? Is it not a “revisiting of the black musical tradition”, i.e. a kind of “structural signifying” that indirectly comments on the work of earlier musicians within the structure of the rap music? (Smitherman, Kolarova)? In other words: is rap not a way of giving new meaning to existing music?

I DO NOT PREACH TO NO DEAD CHURCH

Probably more than anything else, it is the African call-and-response tradition that makes for it that the blues and rap are so closely related as manifestations of the African-American oral and musical culture, which explains too why they can be read, as few other expressions, as an in-depth autobiography documenting the history of the United States (F. Jones). The call-and-response technique, though not unique for blues and rap, is one of their fundamental, vital features. As H.L. Gates Jr. declared in 1996: “Embedded in all aspects of (the) oral tradition is the pattern of call-and-response. It is the structural principle of worship, the unbroken center of secular and sacred forms. It’s never not been there.” (6)

One of the most encompassing definitions of call-and-response is likely the one formulated by Daniel and Smitherman (1976):

“As a communicative strategy this call and response is the manifestation of the cultural dynamic which finds audience and listener or leader and background to be a unified whole. Shot through with action and interaction, Black communicative performance is concentric in quality – the “audience” becoming both observers and participants in the speech event. As Black American culture stresses commonality and group experientiality, the audience’s linguistic and paralinguistic responses are necessary to co-sign the power of the speaker’s rap or call”.

Let me recall at this point one of the basic distinguishing features of the “nommo” quoted by Molefi Kete Asante: “nommo” is an essential collective concept, referring to communal activities. It has no meaning for an isolated individual. The African discourse eschews the distinction between the speaker and the audience. Performing the “nommo” is a mutually empowering event. It can create a sense of shared experience and communal feeling, that is at the same time motivating each other’s actions.

Hence, it would seriously limit our comprehension of the role of call-and-response if we were to see it as only a technique of performance, a singing style. As Paul Garon (1975) convincingly argues, the black cultural values are not in the first place a characteristic of the music, but find foremost an expression in the black performance’s relationship between the music, the performer and his/her audience. Call-and-response, he continues, are the life force of the African-American performer/audience dynamics and communication. What matters, is to see the blues and rap as participant activities, where the singer in the performance of individual emotions simultaneously testifies for the emotions of his community. The performance, however, is ineffective as an expression of black values when there is no dialogue between the individual and the group. Call-and-response are a form of ritualized individual-group relationship, that at the same time fragment and fuse a performance. Call-and-response is the glue that is indispensable for the whole to communicate in an effective way. It is the technique that creates coherence between performer and auditor; it synchronizes speakers and listeners. Without the call-and-response, black communication is lifeless. When a preacher admonishes that he cannot “preach to no dead church” he refers to a church audience where the presence of the spirit is not made manifest by active vocal responses from the audience to the sermon.

Neither for the blues artist, nor for the rapper, the performance can be complete if there is not an entourage that actively responds to and enters into dialogue with the performer. In this way, the call-and-response is more than an opening and closing device, it is a confirmation of the coherence and integration of the group to which performer and audience belong. It is an exponent of social integration. This brings us back again to the act of signifying which is a communication medium between members of the same culture. Call-and-response and signifying are devices that together contribute to community building, and support the maintenance of a common identity.

THE REVOLUTION WILL NOT BE TELEVISED

In what preceded, I did nothing more than to scratch the surface of the relation between the blues and rap, concentrating on a single aspect of what they have in common: the power of the word.

At one point in my writing, I have been tempted to explore some antecedents of rap music in early blues music. Yazoo records has already made an effort in this direction when it issued its CD-2018: “The Roots of Rap Classic Recordings from the 1920s and 30s“, containing tracks from early blues performers such as Blind Willie Johnson, Henry Thomas, the Memphis Jug Band, Leroy Carr and Blind Willie McTell. While evidently Speckled Red’s “The Dirty Dozen” is also part of the track list, I’m missing other names as for instance Son House whose “John the Revelator” involuntarily brings rap associations in my mind. André Lauren Benjamin, aka André3000, aka Dre, rapper, singer-songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, record producer and actor, and probably best known as part of the hip-hop duo OutKast, quoted Son House’s “Death Letter Blues”, and “John The Revelator” in a 2006 interview as “so deep that they take you into another world.” (7)

Others look for the rap antecedents not in the blues, but rather in more recent jazz work of artists as Gilbert Scott-Heron, poet, musician and author whose work fused jazz, blues and soul. His poem-song “The Revolution will not be televised” is sometimes called a form of proto-rap (Patrick Taylor).

But after all, this “roots”-discussion which traces rap back to either 20s blues or later jazz has little sense if we don’t have an ear for what unites them all: the prevalence of the word. Of course, the African originated life-force giving power of the word is not exclusively expressed in the blues and rap, but is as well a vital component of other African-American cultural expressions. It is a vein of African-American culture which flows for instance in slave sounds, story telling, spirituals and gospel, in folk preaching and in political speeches. As for the latter, we need not limit ourselves to the discourses of Martin Luther King or Malcolm X. Only recently, has Sheena C. Howard of the Howard University in Washington, uncovered how the African oral element of “nommo” is manifested in President Obama’s speeches, and how he uses “nommo” to facilitate communication across racial lines (8).

Furthermore, the blues and rap have more in common than just the “nommo”. The use of rhythm, rhyme, repetition, tonal inflections, …. are all most interesting criteria along which these musical genres can be compared. However, above all, the question as to why, for so many blues adepts, the relation to rap music is a tense one, merits additional attention. Obviously, the nature of the differences between the blues and rap is such that many a blues lover asked about his opinion on rap music, will label the latter with words I prefer not to reproduce here. Why? One reason is without doubt that rap music has acquired in large circles a controversial reputation with connotations of (extreme) violence and sexual obscenities. The observation that some (white) rappers have gained fortunes, and have lost touch with the groups that were at the origin of rap, is another explanation. Noticing, moreover, that mainstream integration ensued lucrative offers by large scale companies to promote their products by rappers, will not contribute to a positive image of the genre. Finally, are family disagreements not often the most tough ones?

Though, I will still not, after my first explorations of rap music beyond the thick layer of commercialization, count rap music among my favourite genres, I am glad that I have been able to put aside some of my earlier prejudices, and can start looking for the message that is behind the “waterfall of words”. Concluding with the musing of James McBride (9), author, musician and screenwriter of whom some work is labeled as classic, and is read in schools and universities across the US :

“The music is calling. Over the years, the instruments change, but the message is the same. The drums are pounding out a warning. They are telling us something. Our children can hear it. The question is: Can we?”

_________________________________________________________

Footnotes:

(1) The concept of “nommo” has been introduced to us, mainly by Janheinz Jahn’s study “Muntu : An Outline of the New African Culture” (written in 1958, first published 1961). Using widely drawn sources, heavily dependent on the actual language and practice of Mrican cultures, the scholar attempts to demonstrate the existence of a powerful, closely integrated set of principles which come together in an archetypal pattern at the basis of black African culture. He argues that in spite of all its obvious diversity, traditional Mrican cultures all participate in and derive from a set of philosophical principles that find expression in individual cultures which may differ greatly in terms of emphasis, ritual and cultural detail, through which these principles find expression. However, the adherence to the principles is clearly present. There is common backbone (see also: ARCHETYPAL PATTERNS UNDERLYING TRADITIONAL AFRICAN CULTURES: John Benoit, 1980).

The concept is not without any critics, pointing to the fact that it too strongly ignores differences between African cultures.

(2) The parenthetical ‘g’ denotes the African-American vernacular practice.

(3) African-American speech focus of annual festival February 10, 1998 – Kalamazoo

(4) CMJ New Music Report 1 Jul 2002, p. 17

(5) E. Wald’s new publication, dealing with “the dozens” is scheduled to appear in June 2012 (note April 2012).

(6) New York Times, December 12, 1996 (article by Dinitia Smith)

(7) http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2006/aug/13/popandrock.urban

(8) Howard, S. C. (2011). Manifestations of Nommo in Barack Obama, Journal of Black Studies.

(9) James McBride, Hip Hop Planet, on: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2007/04/hip-hop-planet/mcbride-text

Further Reading:

– http://mathbabe.org/2012/03/12/hip-hops-cambrian-explosion/

– http://realitiesofknowing.blogspot.com/2008/07/black-wholes-in-literature-2006.html

– http://everything2.com/title/There+is+good+rap+music

– Patrick Taylor, Gil Scott-Heron, The Revolution will not be televised, http://www.rapreviews.com/archive/BTTL_revolutionwillnotbe.html

– Bluesnewz@aol.com, Fernando Jones

– Christopher Small, Music of the common tongue: survival and celebration in African American music, 1987

– Rachel Ruben, et al (ed), American popular music: new approaches to the twentieth century, 2001

– LeRoi Jones, Blues People, 1948

– Michael Thomas Carroll, Popular modernity in America: experience, technology, mythohistory, 2000

– Paul Edwards, Kool G Rap, How to Rap: The Art and Science of the Hip-Hop MC, 1982

– Jennifer C. Lena, Social Context and Musical content of Rap Music, 1979-1995, 2006

– Victor Kofi Agawu, African rhythm: a Northern Ewe perspective, Volume 1

– Claudio Baccigalupo, Enric Plaza, Justin Donaldson: Uncovering Affinity of artists to multiple genres from social behaviour data, 2008

– Ali Colleen Neff: Let the world listen right: the Mississippi Delta Hip-Hop Story, 2009

– Jeffrey Carroll, When Your Way Gets Dark: A rethoric of the blues, 2005

– Henry Louis Gates, The Signifying Monkey: A theory of African-American Literary Criticism, 1988

– Geneva Smitherman, Talking that Talk: Language Culture and Education in African America, 2000

– Avron Levine White, Lost in Music: Culture, Style and the Musical Event, n° 34, Sociological Review Monograph, 1987

– Cheryl L. Keyes, Verbal Art Performance in Rap Music: The conversation of the 80′s,

– Carol D. Lee, Signifying in African American Fiction

– Mona Lisa Saloy, African American oral traditions in Louisiana

– Geneva Smitherman, The social ontology of African-American Language, the Power of Nommo, and the Dynamics of Resistance and Identity through Language, 2004

– Alan Dundes, Many Hands make Light Work or Caught in the act of screwing in Light Bulbs, 1981

– Buzzle.com, History of Rap Music

– Gregory Stephens, Interracial Dialogue in Rapp Music,1992

– Ken Ficara, Yo, Blues: Is Rap the Blues of the 90′s?

– Kveta Kolarova, African-American Music as a Form of Ethnic Identification, 2008

– Bert Hamminga, Language, Reality and Truth: The African Point of View, 2005

– Annelies Lantsoght, Identiteitsvorming bij Afro-Amerikanen in een racistische context, 2010

– Simon Johnson, Rap Music originated in medieval Scottish pubs, The Telegraph, 28/12/2008

– Jennifer C. Lena, Social Context and Musical Content of Rap Music, 1979-1995, 2006

– Sherman Haywood Cox II, Nommo – Creative Power of the Word, (www.soulpreaching.com)

– Metamoros and Jonah Begone, The origins of Rap Music (www. Wesclark.com)

– Tricia Rose, Fear of a black planet: Rap Music and Black Cultural Politics in the 1990s, 1991

– Michael D. Linn, Black Rhetorical Patterns and the Teaching of Composition, 1975

– Kermit E. Campbell, The Signifying Monkey Revisited: Vernacular Discourse and African American Personal Narratives

– Arthur K. Spears, Directness in the use of African-American English, 2001

– John Benoit, Archetypical Patterns Underlying Traditional African Cultures, 2008

– Jack Daniel and Geneva Smitherman. “How I Got Over: Communication Dynamics in the Black Community,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 62 , 1976

– Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America., 1994.

– E.A. Ruch and K.C. Anyanwu, African Philosophy. An introduction to the main philosophical trends in contemporary Africa, 1981

– Samuel Floyd, The Power of Black Music, 1996