The Routes of Roots Music

As someone taken enough with alternative country to be reading this sentence, have you been feeling just a little dissed lately? A little put down?

It’s becoming commonplace to see bands and artists congratulated for “breaking free, at last, from the straitjacket of alt-country authenticity,” or even from “trying the alt-country shortcut to authenticity.” The first suggests that seeking connections to American musical roots inevitably stifles creativity; the second that trying to gain something of value from music rooted in time and place is foolish from the get-go.

That post-1995 alt-country artists have been hampered from producing creative work by an exaggerated interest in traditional country or being “authentic” is a cartoonish joke — obvious enough both to those who may have wished that more country music tradition had been taken up in alt-country, and those who were glad it didn’t.

Now we’re regularly told there was too much of it! That’s more than a little reminiscent of the often harshly reductive representation of an earlier roots music moment, the urban “folk scare” of the ’60s. The turning point for the way that outbreak’s fans and practitioners were portrayed was not so much Bob Dylan’s rural electrification project, which sent so many scrambling for somebody’s Fender, fast. It was that scene in Animal House that did it. And you know which one I mean.

Stephen Bishop is sitting there on the stairs, strumming away, a sickeningly earnest, self-involved folkie, singing “I Gave My Love A Cherry”, when a toga-clad John Belushi bursts into a rage, smashing the wimp’s guitar to pieces.

That was it. The folk music boom was now widely understood to have been about boring goody-goodies inflicting songs like that. And wasn’t it?

No. And right about now, it should be a relief to be reminded of it.

Aspects of the ’60s folk scene did wear thin — its tendencies toward pretended “innocence” and “simplicity,” semi-habitual self-righteousness, and worse still, plain blandness. But even if you locate those weaknesses in 90 percent of the output of the folk scare, there was that other, crucial 10 percent, which came from idiosyncratic artists who broke the mold or didn’t quite fit it — and some rare ones who took the plunge into roots far enough to bring something back alive.

The reissued works of Richard Farina with wife Mimi were casually described and dismissed in a recent review as pure “dewy-eyed ’60s.” Farina was anything but — an innovator who stretched traditional dulcimer playing as far the raga subcontinent, a politico with the edge to sing of a “black destroyer” who was Ourselves, a comic who could satirize the Village scene itself, and who, in the last weeks of his too-short life, looked most unamused by alarmed TV host Pete Seeger’s suggestion that he find something more upbeat to sing! (Farina responded with the proto-psychedelia of “Joy ‘Round My Brain”.)

The folk boom was “humorless”? The Jim Kweskin Jug Band was hardly that. “Sloppy hippies who didn’t practice?” That band featured pickers Geoff Muldaur and Bill Keith. “Twangless”? Check out Ian & Sylvia on their way to country. “Unable to digest real country”? Not when the New Lost City Ramblers went at it. “Soulless and bland”? Not when Fred Neil sang — or Odetta! “Too earnest or folklorist”? Not when Dave Van Ronk mixed Piedmont blues, Bing Crosby and Bertolt Brecht at will.

It was no accident that most founders of the country rock that followed — Bob Dylan, Gram Parsons, Neil Young, for three — were folk singers from that 10 percent minority first. Country rock became the “alternative college rock” of that day, fiddles and dobros and steel adding some roots flavor for those dissatisfied with the disconnection and distance of the day’s arena-rock beginnings.

Uncle Tupelo-era alternative country would appeal in similar ways, to the same sort of audience, and for similar reasons. But there’s little to suggest that “demanding authenticity,” as though it were some flea market artifact provenance tag, was one of them. If the notion of “authenticity” is of any use in talking about experiencing music at all, it is in reference to the emotional authenticity that can be shared by a performer and listeners — and that connection has little to do with whether a piece of pop is allegedly rooted, or spanking-new experimental.

Listeners may well find the relative straightforwardness, sometimes even simplicity, of some roots music to be an easier, less mediated environment in which to find that emotional connection. And for some of us, sometimes, there is satisfaction in hearing the sounds of our own place, a place that’s been lived in, outside of time, fads and fashion. Roots music keeps coming back because it satisfies a returning hunger.

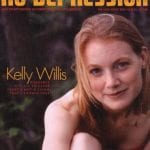

Movie scenario: A young man with thick glasses and a slight goatee mopes on a stairway, strumming, wearing a black No Depression T-shirt, staring at his own shoes. “Sounds like 1963,” he sings, “but for now, sounds like heaven…” “Strum this!” says the no-neck frat boy, grabbing the guitar…

When cartoon dismissals show up, remember the New Lost City Ramblers’ John Cohen, who’s been exploring roots music for 50 years. While interviewing him for these pages recently, I wanted to test his reaction to the notion that the search might have been, as some say, a passing folly — and a dead end.

His eyes flared as he shot back: “I won’t have my life dismissed as a romantic notion!”

He still has his edge, thank you very much. Don’t let anybody tell you that for feeling pleasure with connections in time and place, you must have lost yours.