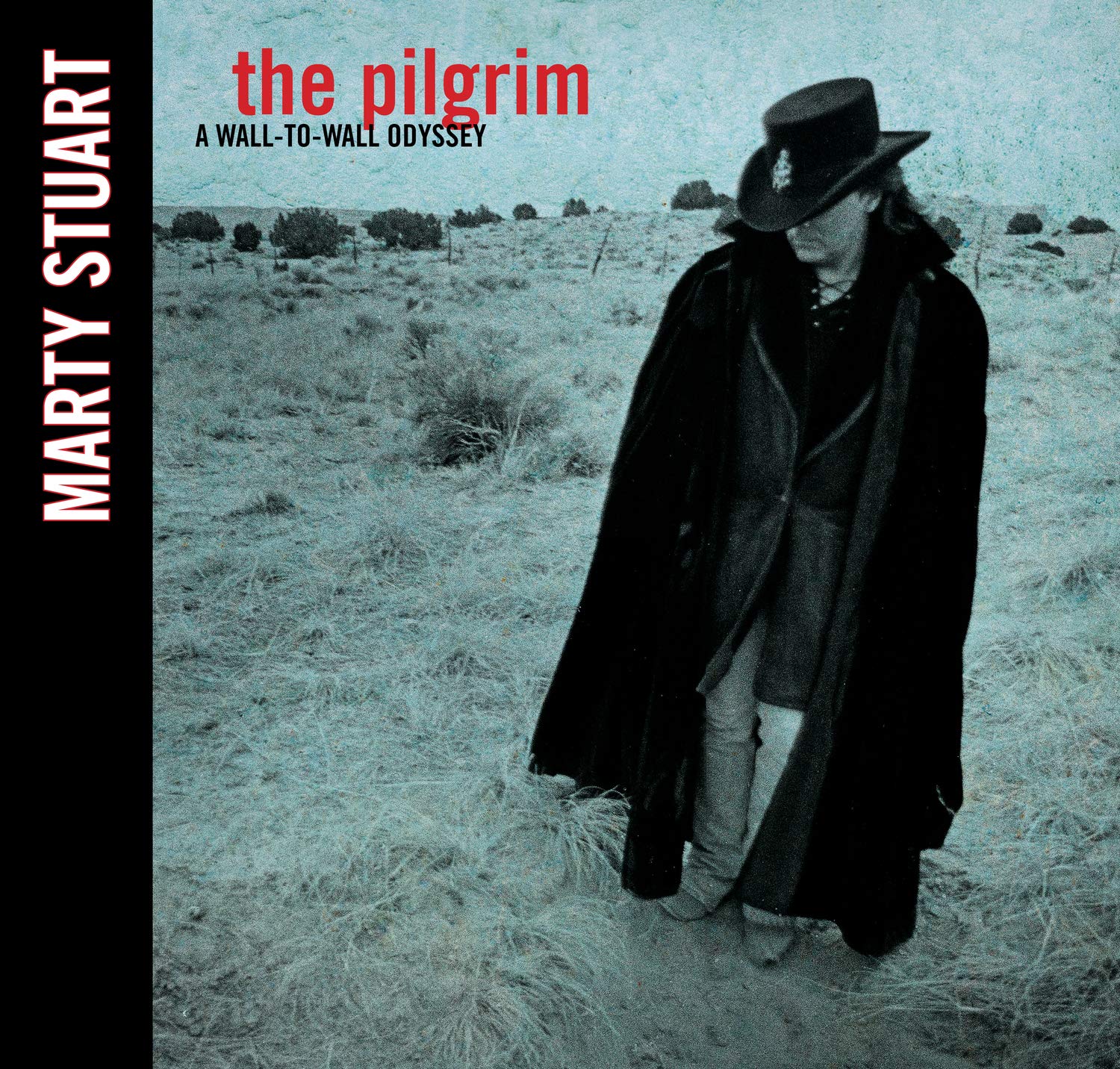

THE READING ROOM: Marty Stuart Recounts the Journey of ‘The Pilgrim’

When George Jones sang “Who’s Gonna Fill Their Shoes?” (Troy Seals/Max D. Barnes), he might not have foreseen that the answer lay in a young guitarist, songwriter, and singer from Philadelphia, Mississippi, named Marty Stuart. By the time Jones’s single hit the charts in 1985, Stuart had already been playing guitar and mandolin with Lester Flatt — Stuart was 13 when he joined Flatt’s Nashville Grass — and by 1980, a few years after Flatt had disbanded his group, Stuart was playing in Johnny Cash’s band. Along the way he played with Roland White, Vassar Clements, and Doc Watson, and released two bluegrass albums. By 1985 he was playing on Cash’s album Class of ’55 at Sun Studios in Memphis with Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Roy Orbison. At the end of those sessions, Perkins gave Stuart his guitar on which he had inscribed: “This box has some hit songs in it, and you’re just the cat to get them out of it.” Stuart released Hillbilly Rock in 1989, unleashing a flood of commercial success in the 1990s with hits such as “Tempted” and, with Travis Tritt, “The Whiskey Ain’t Workin’.”

In 1996, Stuart returned to Sun Records, looking for “another wave of magic,” as he writes in his new book The Pilgrim: A Wall-to-Wall Odyssey (BMG), out Feb. 14. After finishing his second day in the studio, he got word that Bill Monroe has died. On hearing the news, Stuart started to walk and recalls his thoughts at the time: “not having Bill Monroe around was going to take some getting used to. … I reminisced, thinking of the stories told to me by the old-timers about all those years when Monroe’s bluegrass music was dead and generally neglected by the public. …I tried to imagine how lonesome life must have been for him while he struggled to survive, and I heard myself say: ‘I am a lonesome pilgrim far from home / And what a journey I have known / I might be tired and weary, but I am strong / Pilgrims walk, but not alone.’”

He finished two more verses on his walk, and by the time he returned to the studio, he’d written “The Pilgrim,” and he and his band, the Rock and Roll Cowboys (Gregg Stocki, Steve Arnold, Brad Davis, and Gary Hogue) recorded the first version of it. For a year and a half, it was the only song he had for his next project, but it would evolve into a concept. “As it turned out,” writes Stuart, “I wrote the last song first and had to work my way back to the beginning.”

This lavishly illustrated book includes hundreds of photographs — many taken by Stuart himself, who’s a keen-eyed photographer — and a CD with a newly remastered version of the original release and 10 additional bonus tracks. Through it all, Stuart conducts us on his pilgrimage, his odyssey, his quest to discover how his song “The Pilgrim” was the key that unlocked the overall scheme of things. The Pilgrim: A Wall-to-Wall Odyssey is at once the story of the making of the record that established Stuart as a poet, prophet, curator, and storyteller and the story of an album that faded quickly from sight after release.

The Pilgrim wasn’t the commercial success that his label, MCA Nashville, was looking for; after its release in 1999, they canceled Stuart’s contract and shelved the record. But Stuart never lost faith in it, and he reissued it in 2019 with 10 bonus tracks drawn from material he’s gathered over the years. “Going into my archives to search out Pilgrim-related material for this release was like reaching into a dusty old treasure chest,” he says. “I found songs that I’d written and forgotten, photographs I never got around to looking at, unfinished recordings from The Pilgrim sessions, and a string of archival recordings with Earl Scruggs, Johnny Cash, Ralph Stanley & the Clinch Mountain Boys, Emmylou Harris, Connie Smith, and Uncle Josh Graves that I made while they were doing their parts on The Pilgrim. Upon listening, those recordings stand as cherished, sacred documents of American roots music that have waited nobly in the shadows for their invitation onto the world stage of the twenty-first century. So many life lessons were offered in the creative process of making The Pilgrim. Perhaps the toughest of them all was letting go when the record was considered unsuccessful. However, in letting go, I learned that some things do, in fact, come back around.”

At the center of the album is the story of a world-weary traveler who sets out on a journey to end his life after he witnesses a shocking act of violence. After watching his beloved friend’s husband shoot himself in front of his friend — the man’s wife — the pilgrim sets out from Mississippi for the California coast to visit his mother’s tomb and then to walk into the ocean to end his life. The woman whose husband has killed himself contacts the pilgrim, consoling him and pleading for him to return to her. They marry and live a quiet and peaceful life. Stuart weaves the themes of this story — based on real events that happened in his hometown when he was child — into the album.

In many ways, the story’s movement from loss of hope to redemption is the story of Stuart’s experience of making the album. He lost the album, in a sense, when MCA pulled the plug on it and on Stuart’s contract, and then he was redeemed by the powerful themes of the album and its new release.

Stuart writes that “The Pilgrim was the first step in a journey that led me to the outer edge of awakenings of my true musical heart and soul. The Pilgrim also took me back to the bedrock of my upbringing, where the shadows of my mentors loomed large and cast an eternal glow. During this gust of change, the past, present, and future seemed to harmonize and glow, and an air of newness was all around.”

The Pilgrim changed the course of his musical life, Stuart writes: “I had to make this record in order to live with myself. At the time of its creation, all my efforts in the booming country music parade of the 1990s had pretty much run their course. I needed change. I longed for artistic growth and spiritual expansion. I was hungry for a broader task, something that was definitive, epic, monumental. At the same time, I needed to reconnect with the roots of my musical raising.”

“Looking back on twenty years ago, making The Pilgrim was unquestionably the right thing to have done. It was the first in a long line of creative endeavors that have resulted in the most rewarding years of my life,” Stuart writes.

Like Odysseus, Stuart navigated the narrow shoals of roiling waters, avoiding wrecking his ship by following the siren calls of the country music industry. Like Homer’s hero, he’s not immediately recognized, especially in a world blinded by the sheen of gold. He wanders for a spell, telling stories, and finally is recognized for the hero he is. Like Homer’s legendary tale, The Pilgrim: A Wall-to-Wall Odyssey is a spellbinding story of disappointment, heartbreak, hope, and restoration, told as only one of country music’s greatest storytellers can tell it.