THE READING ROOM: Henry Louis Gates Jr. Highlights Music as the Beating Heart in the Black Church

One of the most riveting scenes in American literature is the threshing floor episode in James Baldwin’s novel Go Tell It on the Mountain.

The young protagonist, John Grimes, writhes on the floor of his father’s church, surrounded by the congregation who are praying for his salvation. The scene is at once violent and soul-rending, for John’s father, the preacher of the church, towers over his son in anger over the young boy’s dirty and unwashed soul, for his son’s sinfulness. (There’s a reason, after all, that “Grimes” is the protagonist’s last name.) Lying there on the floor, John struggles through a descent into darkness, seeing in his trance-like state the loneliness and wretchedness of hell; he yearns to “flee — out of this darkness, out of this company — into the land of the living, so high, so far away. Fear was upon him, a more deadly fear than he had ever known, as he turned and turned in the darkness, as he moaned, and stumbled, and crawled through darkness, finding no hand, no voice, finding no door.” As he is led into the light by the congregation and baptized, he hears the sound of singing, and “the singing was for him. His drifting soul was anchored in the love of God.” Baldwin brilliantly captures not only the struggle between light and dark embedded in the language and belief in many Black churches, but he vividly evokes the sing-song language of the Black church, as well as the soul-shaking power of singing and music.

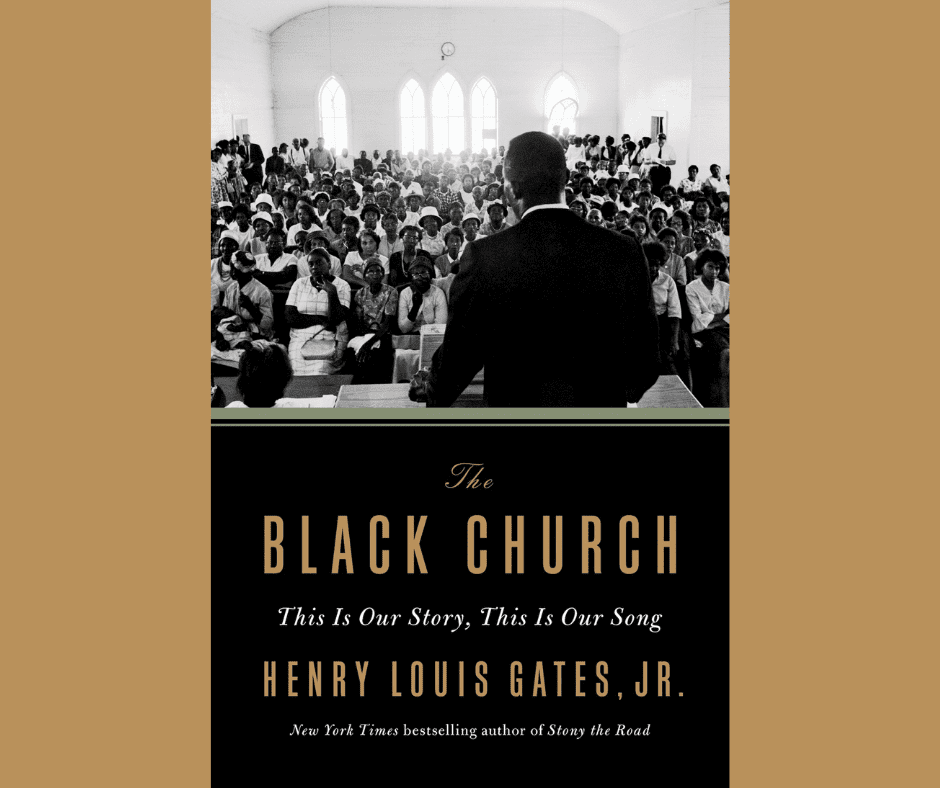

In his eloquent new book, The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song (Penguin), Henry Louis Gates Jr. reminds us of one of the most enduring contributions of the Black church: music. A companion to the PBS series of the same name, Gates’ book starts by recalling the inextricable ways that language and music are woven into the hope and resilience that are inherent in the Black church and that the church provides for the community. As Gates points out, “In the canonical works in the African American literary tradition, no text is more resonantly foundational, more unmistakable than the King James Bible … this tradition reaches its zenith in the prose of James Baldwin. … Baldwin’s literary legacy, in fiction, reached its most sublime extension in Toni Morrison’s mythopoeic fictional universes. But even in these written works, we ‘hear’ the printed word striving to imitate the power of the spoken word, just as Zora Neale Hurston’s fictions mimic secular vernacular forms and Langston Hughes’s and Sterling A. Brown’s poetry sought to make a formal poetic diction out of jazz and the blues.”

Although Gates’s superb book provides a dazzling overview of the Black church and its role in politics — both in producing many notable Black leaders and in providing a sanctuary from persecution and racial injustice — one of the central themes of the book is music, as well as the ways that the Black church shaped aesthetic forms, including singing, dramatic arts, signifying, and call-and-response, among others. As Gates writes, “The signal aspects of African American culture were planted, watered, given light, and nurtured in the Black Church, out of the reach and away from the watchful eyes of those who would choke the life out of it. We have to give the church its due as a source of our ancestors’ unfathomable resiliency and perhaps the first formalized site for the collective fashioning and development of so many African American aesthetic forms. Although Black people made spaces for secular expression, only the church afforded room for all of it to be practiced at the same time. And only in the church could all of the arts emerge, be on display, be practiced and perfected, be expressed at one time and in one place, including music, dance, and song …”

Emphasizing the ways that improvisation can probably be traced to the first hundred years of American slavery — as enslaved people “created, repeated, revised, and improvised” stories that helped them preserve not only their cultural identity but also their self-identity — Gates illustrates the persistence of the tradition of improvisation in various artists. “We see it in jazz, with musicians riffing upon standards in the jazz tradition and in popular culture. John Coltrane did it with ‘My Favorite Things,’ and Louis Armstrong did it with ‘La Vie en Rose,’ to take just two of countless examples. …Daring and defiant artists, ranging from Thomas A. Dorsey, with his experiments in gospel, to Kirk Franklin, with his fresh fusions of hymns with hip-hop, risked the opprobrium of the more conservative keepers of the tradition by daring to alter and infuse the sacred with borrowed techniques from the scandalously secular: that long and controversial tradition of Saturday night sneaking into the church on Sunday morning.”

The church, Gates points out, bred distinct forms of expression, “maybe most obviously its own forms of music. Black sacred music, commencing with the sacred songs the enslaved created and blossoming into the spirituals (which W.E.B. Du Bois aptly dubbed the ‘Sorrow Songs’), Black versions of Protestant hymns, gospel music, and freedom songs, emerging from within the depths of Black belief and molded in repetitions and variations in weekly choir practice and Sunday worship services, would eventually captivate a broad, nonsectarian audience and influence almost every genre of twentieth-century popular music.”

Gates observes that “the popularization of the ‘slave songs’ by the Fisk Jubilee Singers following the [Civil] war led to Antonin Dvorak’s claim, published in 1893, that not only was Black sacred music America’s sole original contribution to world culture, but that the only truly ‘classical’ American music must be constructed on its foundation, a claim that W.E.B Du Bois echoed in The Souls of Black Folk.”

According to the first lady of gospel music, Shirley Caesar, music is integral to the Black church. “If you take music out of the church, preaching is going to cease. It’s something about those songs that brings joy. It helps you to get over a lot of humps that you’re going through in your life, and it might be temporary, but we thank God for that temporary blessing.”

Gates’s book artfully provides a sketch of the history of the Black church and its struggles from slavery times through the Black Lives Matter movement and the church’s struggles in the 21st century. At the heart of his book, though, lies the evocative story of music as the beating heart of a vibrant and resilient Black church.