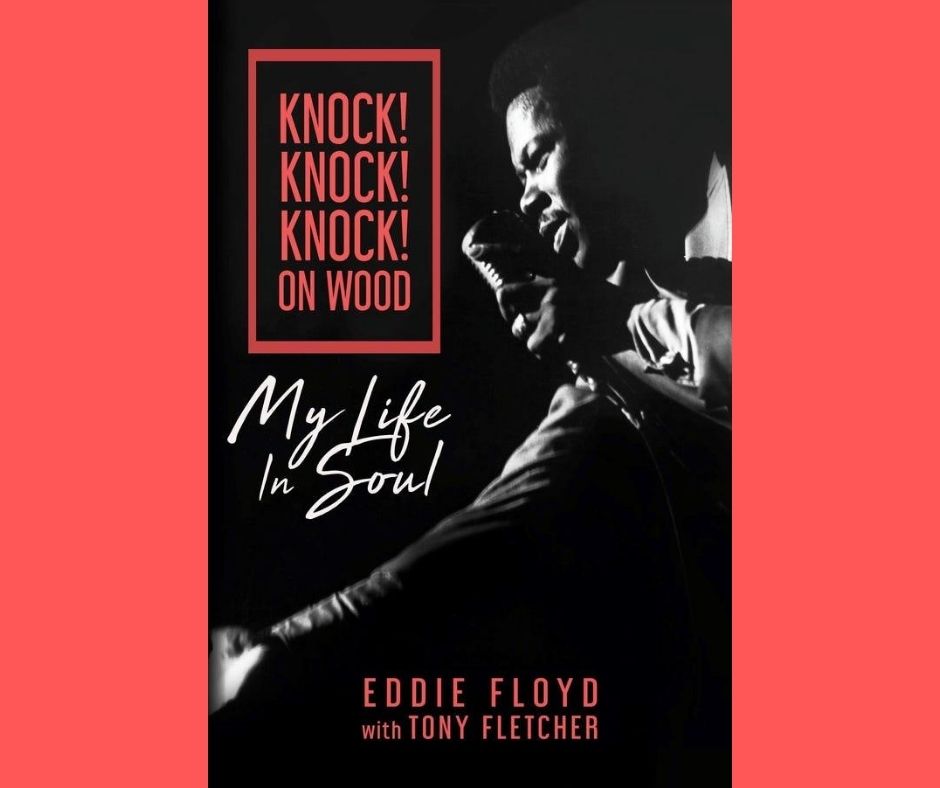

THE READING ROOM: Eddie Floyd on ‘Knock on Wood’ and His Life in Soul

Soul legend Eddie Floyd wrote, or co-wrote, many memorable hit songs, including “634-5789,” “I’ve Never Found a Girl (To Love Me Like You Do),” and “Knock on Wood.” Now, in his autobiography, written with Tony Fletcher, the Alabama native carries readers on a journey through his life, from his stint in an Alabama reform school that shaped his life and his move to Detroit, where he co-founded The Falcons — who are often called the first soul group — to his legendary years at Stax Records in Memphis, where he co-wrote songs with Booker T. Jones and Steve Cropper and where he formed enduring musical and personal friendships with Otis Redding, William Bell, Carla Thomas, and Wilson Pickett.

Stax’s downfall in the mid-1970s didn’t carry Floyd with it — though he’s emotionally connected to the label, of course, and continues to work closely with the new incarnation of Stax, and with younger, aspiring musicians through the Stax Academy. In that era, he continued to perform as a solo artist and with the Blues Brothers Band and Bill Wyman’s Rhythm Kings. A compelling storyteller, Floyd invites readers into his life to experience the ups and downs alongside him in his entertaining Knock! Knock! Knock! On Wood: My Life in Soul.

I chatted by phone with Eddie Floyd about his life and the book recently. Following the interview is a brief excerpt from Chapter 15 (titled “Talk to the Man”) of the book.

Why this book now? What motivated you to write it?

Tony Fletcher had written on Wilson Pickett [In the Midnight Hour: The Life and Soul of Wilson Pickett], and he talked to me for that book. He said, “Why not tell your own story?” So, I got to thinking maybe I should say something. I heard Booker’s [Booker T. Jones] got one now, and I have mine. Now, we just need to get William [Bell] and Carla [Thomas] to write theirs, too. We’re about the only ones left from the original Stax days. (Laughs.)

Had you kept journals? Tape recordings of your reflections? How did you remember all these stories?

Well, you have to remember that before we had tape recorders we just had to remember everything. (Laughs.) I just sort of kept all that together. I have spoken to many of these people every day. You know, I still live it. I didn’t write anything down. Tony would ask me one question and I’d give him 10 stories. (Laughs.) It was all true. We all had one thing in common: music.

What will readers be most surprised to learn about you from this book?

Well, the people I know who’ve been reading the book say, “I can tell you wrote the book. I can hear your voice.” I try to speak exactly pure and with feeling. I enjoy people. I miss my friends in Memphis; I used to go quite often to Stax, but I can’t now with the way things are. I miss them. I talk to Steve [Cropper] at least once a week. We’re still in touch.

What’s your approach to songwriting?

I might be out working here on my farm, and I’ll get an idea. All of a sudden a title will come to me. As soon as the title hits, I start hearing the melody, the hook, the lyrics start coming, and even the song’s tempo, upbeat or slow. I start singing; I’m hearing the changes as I’m singing. Right now, I’m writing a gospel song. I used to write a lot of gospel songs for my mother; she loved gospel music. She used to tell everybody that I wrote those songs just for her. (Laughs.)

What’s your greatest regret?

I don’t have any regrets. I did it my way. I never had a manager. My theory was go and do things the best you can do. People would call me back. I never had a booking agent. If I came to play for you, you’re going to call me back.

Tell me a little bit about your relationship with Wilson Pickett.

You know, it’s funny: Wilson’s house was only 9½ miles from mine in Alabama. I lived in Montgomery, and he lived in Prattville. We didn’t meet, though, until we were both in Detroit. Joe Stubbs was the original vocalist for our group, The Falcons, and when he left Wilson joined us. Pickett wasn’t with us but about a year and a half. On one of our tours, we were driving from a show in Atlanta to one in New Orleans, and I stopped in Montgomery to see my mama, and he stopped to see his. We never got to do that again, but Pickett and I would meet in every country you can name. I was singing with Bill Wyman’s Rhythm Kings when I got the news that Pickett had died. I was singing “634-5789” [written by Floyd and Steve Cropper but most associated with Wilson Pickett] on stage that night, and I broke up in the middle of it.

What lessons do you want readers to take from the book?

Keep it up. Don’t lose faith in it. Music will never die.

What’s next for you?

Just sitting here at the house. I’ve got a big farm. I’m always writing. As long as we’re putting songs together, eventually someone will call.

Here’s an excerpt from Chapter 15 of “Knock! Knock! Knock! On Wood: My Life in Soul.”

TALK TO THE MAN

In 1974, I made what turned out to be my last album for Stax, though, at the time, I never intended or expected that to be the case. We named it Soul Street for the intersection of Mississippi and Walker, the two streets just up above Stax, where there’s a restaurant that’s still there called the Four Way Grill. Best food in the world! Everybody who came from overseas, we’d take them to the Four Way. We had us a little party in studio A making the title track; I brought in about twenty bottles of liquor and got a whole vibe going that you can hear on the record. Had this new group Con Funk Shun in as my band. Got the Nightingales in there doing backing vocals, giving it a gospel feel. What’s that smell? Something’s smelling good!

Almost the entire album was recorded at East McLemore, and in some ways it was like a homecoming after doing my last few records in different places. At the same time, we got some new faces in the studio: not just Con Funk Shun, who went on to have a whole career of their own, but another house band, We Produce Rhythm. And the songs are coming from partners old and new. A couple of the nest, “I Don’t Want to Be with Nobody but My Baby” and “I Am So Glad I Met You,” I wrote with Joe Shamwell, who I knew from back in D.C., where we’d co-written “Got to Make a Comeback,” the B-side of “Knock on Wood.” And I wrote the finale, “Stick with Me Baby,” with the great Luther Dixon, who’d been a partner in Scepter and Wand Records back in the early 1960s, writing hits for the Shirelles, Chuck Jackson, Jimmy Reed, and others. I happened to be with Luther down in Miami, and we just got to writing together. Don’t matter where I am, who I’m with; if an idea for a song hits me, I’m ready to go to work!

The only song we didn’t do at Stax was the first single from Soul Street, “Guess Who.” For that, I went back up to Detroit, with Don Davis, to United Sound. That was one of the first studios I’d ever recorded at, back with the Falcons. During his time at Stax, Don made some big changes at the company, brought in some excellent people. Among them was Tim Whitsett to run the publishing companies. (I was signed to the main Stax songwriting arm, East Memphis, though there was another called Birdees.) But Don also upset a lot of people at Stax with his quick success and, after promoting him above some of the other people who’d been producing hits at Stax a lot longer than Don, Al Bell had to let him go. Don, though, was a savvy businessman and, back in Detroit, he purchased United Sound, modernized it, set up a publishing and production company called Groovesville, where he carried on making hit records.

Unfortunately, the song we did together, “Guess Who,” wasn’t one of them. It was real smooth — smoother than almost anything I’d done before — a good reflection of where Don was at, and a sound I was happy to get under my belt, though maybe not what people were expecting from me at the time. I didn’t write the song either and wasn’t too often I’d let that happen on a single unless, like “Bring It on Home to Me” or “My Girl,” it was already well known and something I felt I could put my spin on.

But other than that, I think of Soul Street as my Memphis album, and partly because of the cover, probably the best album sleeve I got. The photographer came down to Main Street in Memphis and took a picture of me sitting on the steps of Sammy’s, the best tailors in the city at the time, with all other people going about their business on the street in front of me. Then they took that photograph and did a painting of it. All the people that you see on the cover — including the guy in the three-piece pink suit out front of Sammy’s — were real people that were there that day. The picture captures the mood of that era, kind of a Superfly time. Sammy’s has moved now — it’s in midtown, in a mall — but at least it’s still around.

That was more than was going to be said of Stax within a year. We knew it was falling apart because they weren’t playing our records on the radio anymore. But at the same time, I wasn’t in the administration part of it; I was a singer who doesn’t walk into their office and ask them what bills they owe anybody. How would we know? You have to wait and hear what happens. You hope it’s all going to work out.

…

That turbulence seeped into my songwriting. After a couple of the singles from Soul Street didn’t do much — and there ain’t nothing wrong with that album that some decent promotion and distribution couldn’t have fixed — I wrote a new one with Joe Shamwell: “I Got a Reason to Smile (’Cause I Got You).” Sounds like another love song, and ultimately it is, but the first verse kicks right off talking about waking up in the morning to yesterday’s problems, about having to get up and get on with the struggle. In my song, the resolution is that, yeah, things may be hard, but I still got you. In Memphis, we were feeling that, yeah, things may be hard, but we still got Stax.

A similarly dark mood seeped into my very last new single for Stax, released in the spring of 1975. Just the title, “Talk to the Man,” should give you a hint that it’s not my usual fare, and sure enough, the end of each verse confirms as much: “We got to get on our knees every time we talk to the man.” That was the state of the world at the time, and it was very much the state of things around Stax. In an attempt to stay positive — and also being unwilling to give up on a good song — we put “I Got a Reason to Smile” on the flip side this time.

If you know anything of me by now, you know that I work hard. I do what’s necessary to assure myself of the best results possible. So I hear that there’s a booking agency in Georgia, they’re reporting on all these country stations playing “Talk to The Man,” and that’s a great thing for me: I have no musical boundaries. This booking agent, she’s telling me she thinks the song can become a hit, certainly locally, but she can’t get any help from Stax, that there’s but nobody working there for her to talk to anymore. And now I’m getting action in Indiana as well, for “I Got a Reason to Smile,” so I go up there to do a show. I get into town with my record and I actually go to the distributor, because that’s what we would do in a lot of places; I’m trying to show good will, that I’m working my record, and that they should be getting it in the shops. And that’s when they tell me they don’t have the record because they can’t get the record. Well, how come?

It was round that time that William Bell’s contract expired, and he politely declined to renew. “It was tough going because Stax owed money to CBS,” he recalls now, “and there were some other things going on with the systems changing, different personnel, so it was just a downward spiral for Stax. The originals like me and Eddie and Isaac who’d been there for a while, we could see the handwriting on the wall. For me I still had family, I had car notes and home payments that I’ve got to take care of, so I had to make the move.” The Emotions got out of their deal round that time too. Then the Staple Singers demanded their freedom, and that ticked Al off to no end after all he felt he’d done for them. Another of the label’s newer hit-makers, the Soul Children, left as well — for CBS, to be produced by Don Davis!

Me, I stayed right where I was. This is what I told the Tri-State Defender, the region’s leading black newspaper, that June of 1975: “I came to Stax with Al Bell. He brought me here and unless he puts me out, I’ll be here ’till he takes me from here myself. I’ve had hard times before, but hard times they come and go. In the past, when they came, Stax stuck by me — so now I am sticking with Stax. I am sorry for the problems the company has had but I’ve never been sorry for a minute that I came here with Al.”

And you know something, I’ve still never regretted that. Al and I had something deep, and it’s obvious in what he said just recently, when we started working on this book. “What hurt me so badly, candidly, is that I couldn’t do for and with Eddie what Berry Gordy was able to do with Smokey Robinson.” I appreciate that he thought that much of me.