THE READING ROOM: Books to Help Keep Music on Our Minds

Back in 1994, Laurie Garrett, the health and science reporter for Newsday, wrote a book titled The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World out of Balance (FSG). While she didn’t predict the novel coronavirus that is now spreading through the world, she issued some stern warnings that clearly no one heard very well.

Garrett focused on the history of disease to illustrate that while antibiotics and vaccines had eradicated many diseases — at least in 1994, smallpox had been virtually wiped off the face of the earth, and cases of tuberculosis were few and far between, and even measles had begun to shuffle of this mortal coil — we had let down our guard and been lulled into a sense of false complacency. She talked to a range of epidemiologists and examined the ways that climate change, environmental disasters, and refugee migration, and economics had created, and would continue to create, conditions that were ripe for outbreaks of new diseases resistant to treatment and cure and that would allow such diseases to migrate around the world, sometimes unstoppably. Garrett also demonstrated that we, especially in the US, have shifted our focus to private health and moved away from a robust focus on public health, much to our peril.

In 1994, despite the picture she painted of “coming plagues,” Garrett was nevertheless optimistic that if we could turn our attention to public health and some research we could be prepared for outbreaks of any such epidemics that came our way.

I’ve been thinking about Garrett’s book a good bit over the past month or so, of course. I read it back in 1994 when I was teaching medical ethics and was using the book in my class. Reading it back then was unsettling enough, but thinking about the book now and the ways we’ve lost or squandered lessons from history over the past 26 years makes me angry and disheartened. We are now living in times from which we’ll emerge stronger (we hope), chastened (we hope), less selfish (we hope), and more community-oriented (we hope). As the world as we know it changes around us, perhaps we’ll emerge on the other side of this pandemic with some idea of how to foster the common good — a difficult idea for most Americans so focused on individual well-being and wealth to embrace, to our peril.

Even in the midst of the pandemic, as we are sequestered in our dwellings, we find solace in books and music. Maybe this is a good time to re-read — or read for the first time — The Coming Plague, but there are a number of other books and records to which we can retreat for solace and comfort, for entertainment and instruction. As we all know, great art emerges from plagues and pandemics. Shakespeare is said to have written King Lear while he was quarantined from a plague in the early 17th century, and Daniel Defoe’s novel A Journal of the Plague Year offers a fictional account — which reads as a nonfiction chronicle — of London plague of 1665.

Indeed, there is no shortage of good reading about plagues and epidemic illnesses. First and foremost, of course, is Albert Camus’ The Plague, written in 1947, a novel about the Algerian seaport town of Oran that is closed down due to the bubonic plague. Many interpreters have read the plague as a metaphor for fascism, but, even so, the novel instructively raises questions about human nature and our response to being locked down in one place with death all around us. Some characters look on the plague a God’s punishment, others are heroic in their altruism. Read it today and you can easily pick out public figures that resemble one of the novel’s characters. One of the most memorable lines from the novel resonates today: “Thus each of us had to be content to live only for the day, alone under the vast indifference of the sky.”

Given the persistent rhetoric about being at war with an invisible enemy, Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor speaks loudly to our current situation, as it illustrates the shortcomings of such rhetoric. While Sontag — who was struggling with cancer when she wrote it — has been criticized for not revealing her personal struggle as she was writing the book, her book remains as timely as when she published it in 1978. She points out that “illness is not a metaphor, and that the most truthful way of regarding illness — and the healthiest way of being ill — is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking.”

These books I have mentioned thus far, along with Bocaccio’s Decameron (10 wealthy folks leave Florence during the plague and over 10 days each tells 10 stories) and Sinclair Lewis’ Arrowsmith (an idealistic young American doctor invents a cure for the plague, but with unexpected and sad consequences), provide a good start for a reading list for these days, if only to see ourselves reflected in the mirror of past attempts to cope with such a situation.

Yet, there are plenty of other good books to help us make through the dark night of the body and soul, and many music books to keep us singing and revisiting the music we love. Here’s a short list of a few music books that take us there.

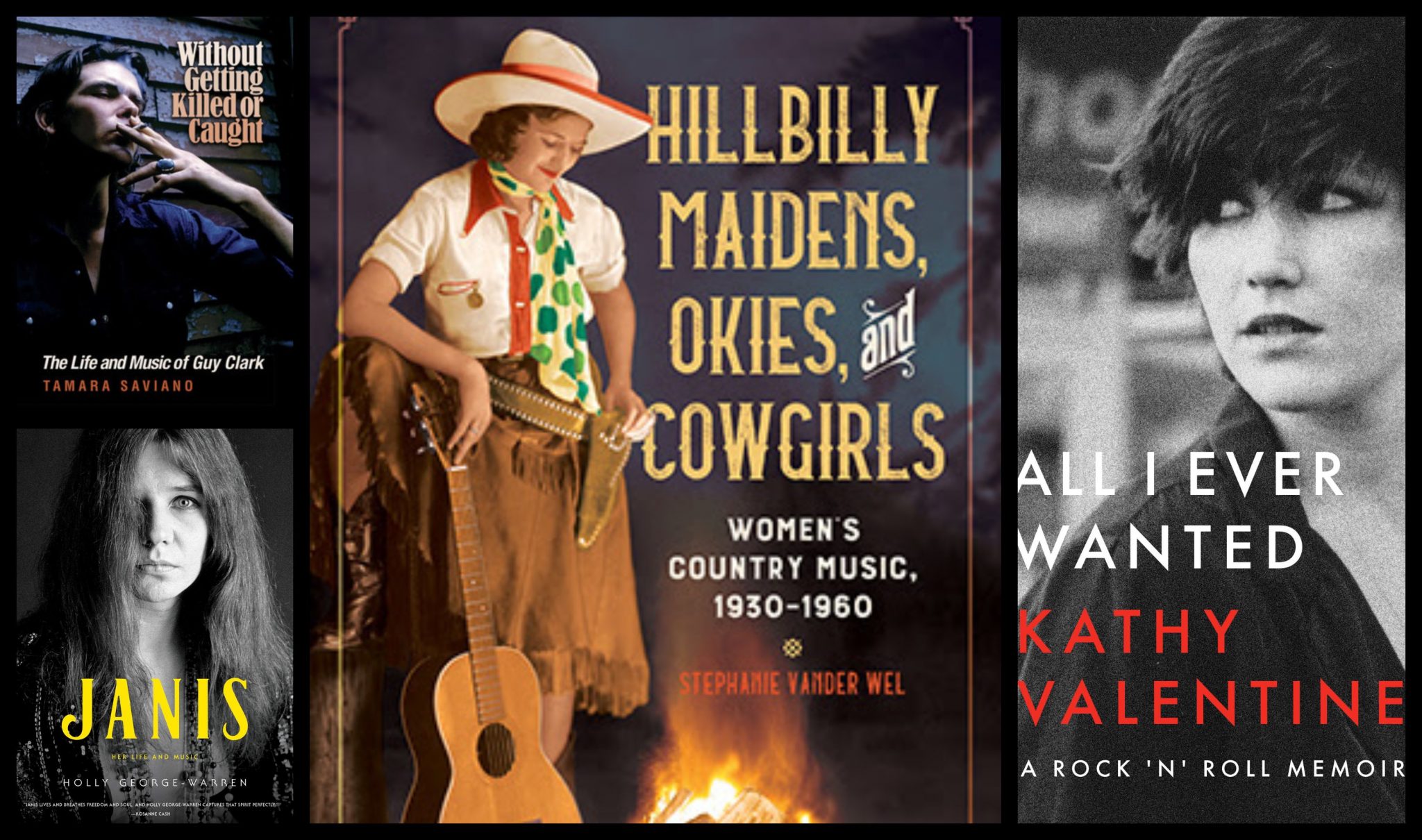

Stephanie Vander Wel, Hillbilly Maidens, Okies, and Cowgirls: Women’s Country Music, 1930-1960 (Illinois) — An excellent analysis of Rose Maddox, Patsy Montana, and Kitty Wells, among others, and their innovative ways of negotiating an industry that hemmed them in as cowgirls or honkytonk angels.

Kathy Valentine, All I Ever Wanted: A Rock ‘n’ Roll Memoir (Texas) — Valentine, the bassist for the Go-Go’s, tells a captivating tale of the ups and downs of the rock-and-roll life.

Bill C. Malone and Bobbie Malone, Nashville’s Songwriting Sweethearts: The Boudleaux and Felice Bryant Story (Oklahoma) — The first complete biography of the Bryants and their monumental and enduring contributions to songwriting and popular music, written by the power couple of country music history writing.

Aaron Cohen, Move on Up: Chicago Soul Music and Black Cultural Power (Chicago) — One of the best books on the evolution of soul music in Chicago.

Ellen Willis, Out of the Vinyl Deeps: Ellen Willis on Rock Music (Minnesota) — A collection of Willis’ essays for the Village Voice and the New Yorker that captures her wisdom and sharp ear for rock criticism.

Tamara Saviano, Without Getting Killed or Caught: The Life and Music of Guy Clark (Texas A&M) — Saviano’s biography of Clark remains one of the best music books in recent years.

John Prine, John Prine Beyond Words (Oh Boy) — Prine collects photos, song lyrics, and autobiographical musings in this delightful collection.

Ray Benson and David Menconi, Comin’ Right at Ya: How a Jewish Yankee Hippie Went Country, or, the Often Outrageous History of Asleep at the Wheel (Texas) — Benson’s mesmerizing storytelling skills go full-tilt boogie in this entertaining memoir.

Holly George Warren, Janis: Her Life and Work (Simon & Schuster) — The definitive biography of Janis Joplin.

Taylor Jenkins Reid, Daisy Jones & The Six (Ballantine) — A coming-of-age tale and the volatile rise of a band.

I hope you are finding some comfort and entertainment reading these days. This list is a meager starting point, but these books will carry you out of yourselves for a few hours or days. Even in these unsettling times, Jackson Browne’s words give us hope: “Well, I’ll keep on moving / Things are bound to be improving / These days / One of these days.”