THE READING ROOM: Bob Dylan Reveals Little in Musings on ‘Modern Song’

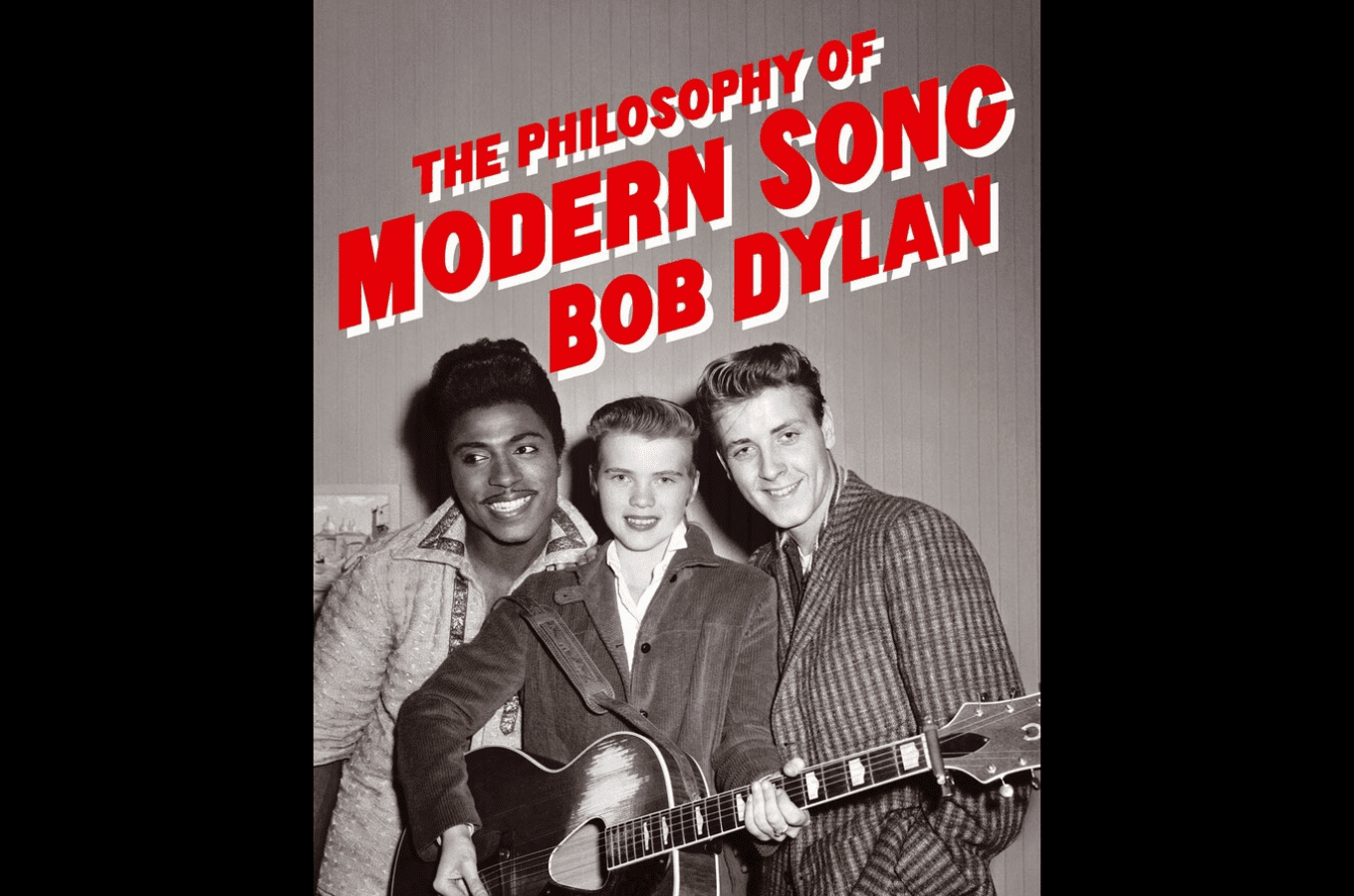

This should be an easy review to write, right? Here beside me is Bob Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song (Simon & Schuster), his long-awaited new book, and the first since the Nobel Committee awarded him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016.

What is there to say here? That it’s a book by Dylan should be enough to recommend it, right? Surely there are several thousand readers who plunked down $45 this week to read Dylan’s take on what the title promises. Surely, too, there will be a few of those folks who wish they hadn’t spent the money and had stuck with his albums instead. Others will discuss the book long into the night, gleaning any morsels of knowledge the enigmatic songwriter tosses out to the gathered disciples. Many will buy the book because it is, after all, written by Bob Dylan, only to grow weary of meandering though disconnected, dreamy riffs about songs unrelated to one another, expect perhaps that they are “modern” (most are from the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s); Dylan offers no rationale for selecting these 66 songs and juxtaposing them as he does.

Anyone expecting to discover Dylan’s philosophy for his own songwriting will be disappointed. Inasmuch as he is writing about songwriting, he’s doing it via brief essays on ideas that, in his mind, tumble out of these songs. Each chapter contains a brief essay about the song itself, as well as short meditation on the themes of the song, or the philosophical issues that Dylan ponders as he thinks about how the song works. In the chapter on The Osborne Brothers’ “Ruby, Are You Mad?” Dylan writes: “This song speaks in the mother tongue, at breakneck speed — rapid quick fire, hardcore, and irresistible — close as it comes to alchemy and reckons what it’s worth. Right on point, it’s keen to drive you mad, and it’s all about Ruby … the gal who can restore you whatever you’ve lost and then make you lose it again. Ruby is just as she is, switched on, plugged in and lady like.”

Dylan then reflects on the nature of bluegrass music, comparing it to a different musical style: “Bluegrass is the other side of heavy metal. Both are musical forms steeped in tradition. They are the two forms of music that visually and audibly have not changed in decades. People in their respective fields still dress like Bill Monroe and Ronnie James Dio. Both forms have a traditional instrumental lineup and a parochial adherence to form.” Dylan’s tongue-in-cheek comments comparing bluegrass to heavy metal — though he appears to be earnest — reveal in a few words the connections Dylan always seems to be making between various musical forms.

Waylon Jennings’ “I’ve Always Been Crazy,” to Dylan, is a song “where you’re giving some hard-earned advice to the woman who’s thinking about giving her heart to you.” As he reflects on the song, he writes, “sometimes songs show up in a disguise. A love song can hide all sorts of other emotions, like anger and resentment. Songs can sound happy and contain a deep abyss of sadness, and some of the saddest sounding songs have deep wells of joy at their heart.”

Of Cher’s “Gypsies, Tramps, and Thieves,” he writes humorously, “gypsies, tramps, and thieves could easily be the answer to the question, ‘Name three types of people you’d like to have dinner with.’ It depends on what you’re eating, doesn’t it? Then again it doesn’t really matter what you’re eating, all that matters is who you’re eating it with.”

Sometimes Dylan points out a singer’s style, as he does with Bobby Darin on “Beyond the Sea”: “His phrasing, especially on a pop ballad like this, is the driving wheel of the production. Time and time again he’ll slip the first few words of a line upstairs into the end of the previous line. He’s very subtle and you don’t realize he’s doing this … He’s a playful melodist and he doesn’t need words. He keeps it simple even when he’s singing about nothing. The sea, the air, the mountains, the flowers. It all floats. It never touches the ground.”

Over 150 carefully selected photos run through the book, each with a brief poetic riff superimposed over it. For example, the photo of an outlaw aiming a revolver at the photo’s viewer appears at the opening of the chapter on Marty Robbins’ “El Paso”; over the photo is a poetic meditation on the song: “In a way this is a song of genocide, where you’re led by your nose into a nuclear war, ground zero, New Mexico where the atom bomb was tested.” Reading these little reflections is like stumbling into a Richard Brautigan novel where the hazy images make sense to those already in on the secret of the poetic language he uses.

We discover in The Philosophy of Modern Song — if we didn’t know this already — that Dylan simply loves to hear himself talk and spool out ideas about these songs. Listening to him talk grows tiresome after a while — even if it is Bob Dylan — and the book is best read in small doses, preferably listening to the songs about which he is writing.