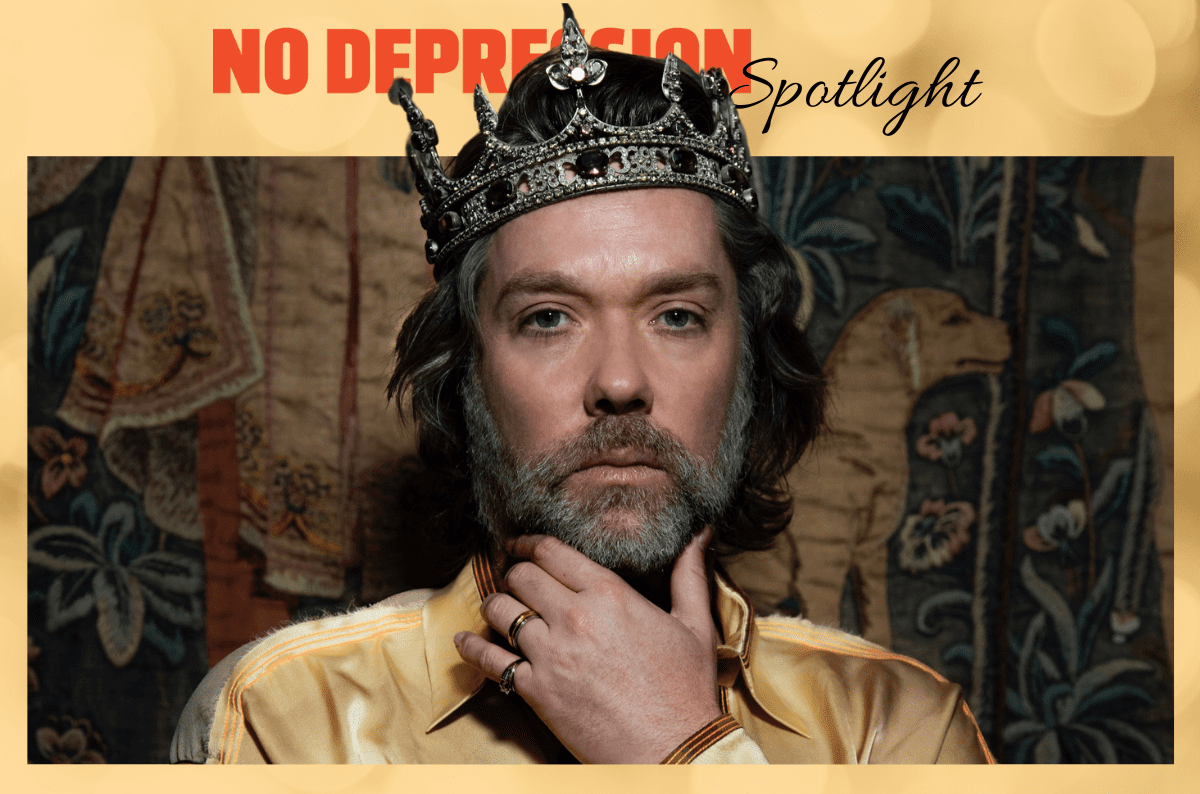

SPOTLIGHT: Rufus Wainwright Brings Folk Legacy Forward on ‘Folkocracy’

Photo by Miranda Penn Turin

EDITOR’S NOTE: Rufus Wainwright is No Depression’s Spotlight artist for June 2023. Look for more from Wainwright and his new album, Folkocracy, out June 2 on BMG, all month long.

One of Rufus Wainwright’s earliest memories is of sitting alone among the thousands of seats in Carnegie Hall, watching his mother, folk singer Kate McGarrigle, during her soundcheck.

“It was a very luxurious feeling,” he laughs, admitting the obvious. Growing up in a house with his mother singing to him and his sister, Martha, most every night, many of those songs took root in his subconscious, refusing to leave no matter how many stylistic twists and turns he took over the years.

With a career spanning everything from Tin Pan Alley-influenced vocal pop to opera to scoring a selection of Shakespeare’s sonnets, it may appear that Wainwright has done his best to distance himself from his namesake, his roots, his birthright. And he has. Yet, as he turns 50 this summer (July 22, to be exact), he’s blending childhood memories with new experiences, and inviting a plethora of artists from across the musical spectrum to join him on his new album, Folkocracy.

Back to the Source

“There is something about really going to the source once you’ve hit the halfway point, and getting what you need to continue the rest of the journey,” Wainwright reflects. That source, of course, is folk music, the music of his family, several of whom appear on the new album. Martha and half-sister Lucy Wainwright Roche contribute vocals to the traditional “Hush Little Baby” as well as “Wild Mountain Thyme,” where they’re joined by Lilly Lankin, Chaim Tannenbaum on banjo, and Rufus and Martha’s aunt, Anna McGarrigle, on accordion. Wainwright refers to his family as a “bona fide folkocracy.” Much like the Seegers, the Wainwrights, Roches, and McGarrigles comprise a family with a rich musical legacy. In fact, Folkocracy began as a tribute to that legacy.

Ultimately, Folkocracy morphed into an album-length examination of what folk music means to Wainwright. It’s not a staid genre from long ago to be admired from a distance at a museum or in an archive. In the hands of Wainwright and his collaborators, folk becomes, once again, a living, breathing, vital music that pulls from multiple styles, cultures, and continents. Produced by Wainwright with Mitchell Froom and David Boucher, Folkocracy was recorded in various studios around Los Angeles and in Montreal. Wainwright relied on Froom, who’s produced albums by Los Lobos, Suzanne Vega, Elvis Costello, and many others (including Wainwright’s own Unfollow the Rules in 2020), throughout the project for guidance and suggestions.

“I made the initial list of songs, about 30 or 40 of them,” Wainwright says. “And I just gave it to [Froom] and said, ‘You choose. I trust your judgment.’ And as that process happened, ideas came up of people who could join us.”

The guests on Folkocracy represent the broad definition of folk music Wainwright champions. They span generations, cultures, and musical styles. “One of the main things we thought would be fun for the listener is if we heard some of these performers singing in a genre we’re not used to hearing them in,” Wainwright explains. “John Legend singing a Peggy Seeger song, for instance, is a really interesting juxtaposition.” Seeger, from that other famous folkocracy, is represented by a moving version of her anthemic yet deeply personal “Heading for Home,” which features strong performances from both Legend and Wainwright.

Seeger was also the wife of late songwriter Ewan McColl, whose “Alone,” in a sparse and haunting arrangement, opens Folkocracy. The song is adorned with only the vocals of Wainwright and of rising star Madison Cunningham, a Grammy winner for Best Folk Album for 2022’s Revealer who also contributes guitar on the track, as well as most of the album. “She’s having such a moment right now and it’s so wonderful to watch,” Wainwright gushes. “It was exciting to be near someone who’s experiencing such a rise on a very fundamental level. She’s really respected by so many musicians from different genres.”

For Cunningham, who’s recently opened for Harry Styles and will be hitting the road this summer with Hozier and with John Mayer in the fall, the opportunity to play such a large part in the making of Folkocracy was quite surreal. “I can’t stress how big of a deal it was to me,” she says. “Because Rufus is my all-time hero and inspiration.”

When she first arrived at the studio, it was only the third time Cunningham and Wainwright had been in a room together. Still, everything fell into place rather quickly. “Rufus is the ultimate professional,” she says. “He walked in with his shit together.” The other musicians — including Greg Leisz, David Piltch, Ted Poor, Val McCallum, and Jacob Mann — were able to sync up immediately. Cunningham and Froom provided most of the backing throughout, with string arrangements on a couple of tracks by Rob Moose.

The Light

Stretching the definition of folk music to fit his vision, Wainwright gathered a modern-day equivalent of The Mamas & the Papas to take on that band’s ebullient “Twelve-Thirty (Young Girls Are Coming to the Canyon).” Filling the Mama Cass and Michelle Phillips roles are Susanna Hoffs and Sheryl Crow, while Chris Stills (son of Stephen — another possible folkocracy in the making) represents Denny Doherty to Wainwright’s John Phillips. They approached the arrangement in a very clinical way, according to Wainwright.

“We wanted to do exactly what The Mamas & the Papas did. We mirrored their harmonies exactly. We didn’t stray too far from the original. We did like a Library of Congress dissection of it. Like, ‘How does this song work? How does this arrangement work?’ It was just a way to be as faithful to the original as possible.”

As far as the song’s placement on Folkocracy, “Rock is now folk,” Wainwright laughs. “I mean, it’s the right amount of time, 50 to 60 years. That’s sort of the litmus test if a song is worthy to continue to be interpreted. And I feel that song deserves as good a chance as any.”

Another track plucked from the rock era is “Harvest,” the swaying title track from Neil Young’s 1972 masterpiece. Wainwright reached out once again to Chris Stills, along with Andrew Bird, to deliver a faithful, yet fresh take on the laid-back classic. While Wainwright has performed the song several times and is a big fan, that wasn’t always the case.

“I didn’t get Neil Young for a long time,” he admits. “When I was a teenager, I was kind of turned off by him and all the Crosby, Stills, and Nash stuff. I just didn’t understand it. But then I fell in love with a junkie in Montreal, and he was a big Neil Young fan. So I really did a deep dive into his music. I had to kind of go to a dark place to really get him, which makes sense.” He pauses, then laughs, “Though I’m not suggesting anybody discover him that way.”

The Dark

Folkocracy also examines folk music’s long romance with dark narratives. The album’s first single, “Down in the Willow Garden,” is an Appalachian murder ballad with origins in the early 19th century. It’s also been referred to as “Rose Connelly” and is believed to have traveled over to the States from Northern Ireland. Wainwright’s first exposure to this gruesome tale came from The Everly Brothers’ version on their album of folk standards, Songs Our Daddy Taught Us.

Acknowledging the violence in the song’s lyrics, Wainwright reached out to Brandi Carlile for levity, to add her vocals to an unsettling, yet beautifully haunting version. “I think with two guys doing it in this day in age would be pushing the envelope a bit too hard. It is a troubling piece of music,” he admits. “But things like that happened, you know? A lot of those murder ballads stemmed from real situations and were a way to process that violence, which as we all know is a big part of the American story. And by not singing about it, I mean, you’re just suppressing something that’s going to get out anyway, so it might as well get out in a song.”

Cunningham has a more light-hearted point of view. “I’m quite a sinister person,” she says, dryly. “I love murder documentaries. I love murder [laughs]! So you could say that song is right up my alley.”

Protest songs, of course, are as much a part of the folk tradition as murder. On Folkocracy, Wainwright examines this side of the tradition with a reimagining of his own “Going to a Town” (originally included on his 2007 album, Release the Stars), with an assist by longtime friend, singer-songwriter, and visual artist Anohni. “I wanted to put at least one of my own songs [on the album],” Wainwright says. Froom suggested ‘Going to a Town,” “mainly because it follows a great tradition of political awareness,” he continues. “Of having something to rally toward. And I wanted my friend Anohni on it. She’s always been very cutting-edge in her activism, her belief system, and the life she’s chosen to lead.”

Another song that falls under the protest banner, but does so in a hypnotically beautiful way, is the Hawaiian ballad, “Kaulana Nā Pua.” “The lyrics are astounding,” Wainwright says. “It was written by a woman (Eleanor Kekoaohiwaikalani Wright Prendergast) who was in the court of the last queen of Hawaii. It’s a total indictment of the United States and their desire to annex Hawaii and what that would mean for the native people. It’s so beautiful, yet it’s also kind of masked, as the words themselves are incredibly sharp.” Wainwright enlisted pop singer Nicole Scherzinger to deliver the song’s ethereal backing vocals. “Nicole doesn’t usually sing anything like that,” he laughs. “But she is Hawaiian, so there was at least a grain of truth that perhaps wasn’t as obvious as one would initially think.” Wainwright says that it was his husband who requested he sing a Hawaiian song and suggested a language coach. It took two coaches and hours of practice to get it right.

Cunningham also found “Kaulana Nā Pua” challenging, but ultimately rewarding. “That song really struck me how difficult it was to play,” she admits. “I spent a lot of time on the guitar part because I just knew it would be obvious if I was wrestling it down or struggling with it. I mean, Rufus was also learning how to sing in that language. In hindsight, I was amazed at how breezy it sounds, and I think that was the goal.”

Getting to the Truth

Another standout on Folkocracy is a radically different version of “Cotton Eyed Joe,” featuring powerful vocals from one of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s newest inductees, Chaka Khan, and based on a moving live arrangement by Nina Simone that breathes new life into the standard. “When I approached Chaka Khan about doing the song, I played her that version and she said, ‘Oh, that reminds me a lot of my dad,’ because there’s a gospel feel to it, so I guess it harkened back to that part of her life,” Wainwright says.

Folkocracy’s most successful accomplishment is how it reminds listeners of the power of the music it celebrates, no matter its origin. It’s all about getting to the truth, to what’s real.

“Folk music always has a menacing quality,” Wainwright explains. “It’s a genre that plays with both the light and the dark and the battle between those two. Unlike disco or most pop music, where you’re trying to create a whole new world that’s about escapism or crafting a fantasy land, folk music is rooted in the real, and therefore it’s timeless. It doesn’t belong to any particular era.”