Little Miss Cornshucks – A soul forgotten

Little Miss Cornshucks

Almost everyone knows the song “Try A Little Tenderness.” Most remember it as the soul ballad nailed by Otis Redding in 1966 — based, he always said, on ideas heard in performances by Sam Cooke and Aretha Franklin a few years before. Some recall its origins as a sentimental number recorded by Bing Crosby, Ruth Etting and others in the early 1930s.

But almost no one remembers how the song first jumped from crooners to modern soul — transformed by a diminutive singer dressed as some down-home bumpkin just come to town, sitting on the edge of a stage, barefoot and weary, actually wearing that “shabby dress” of the lyric, and just letting it wail.

On the forgotten 1951 recording by that singer, the song cuts across the space from microphone to speakers, and then across the years, with an almost embarrassing intimacy, an intimacy never to be forgotten by those who have heard it. The record begins with a low sax moan, and her singing builds to a heart-rending, pleading ending: “Awww-oh…oh, it’s so easy — try a little…tenderness!” It sets the pattern for all the famous versions which followed.

Today, most people have never heard of that powerful performer, let alone had the chance to hear her music. That’s as large a distortion in the American musical record as the now-corrected neglect of “Lovesick Blues” songster Emmett Miller.

She was called Little Miss Cornshucks.

Miss Cornshucks was, above all, a unique live performer. She riveted audiences from Los Angeles to Chicago to New York in the post-World War II years, the “after-hours blues” era between swing and rock ‘n’ roll, when the break between jazz and popular R&B was not yet a chasm.

She was not a back-country singer of acoustic folk blues. She did not fit the scat-singing “Great Lady with precision vocal instrument” model favored by jazz critics and historians. Neither did she provide the cool rebel or dead-by-25 personal story often sought by those looking for proto-rock romance. Thus, she’s fallen between the card files of chroniclers of all forms.

Little Miss Cornshucks has merited but a line or two in any available reference work, with not even basic facts — her birth and recent death dates, her married name — accurately reflected. But she has been mentioned repeatedly in the memoirs of R&B, jazz and vaudeville performers alike, as a personal favorite and as a singular influence.

Ahmet Ertegun, the storied chief and co-founder of Atlantic Records, chose to begin What’d I Say, his recent memoir of the label’s rise to dominance in soul, jazz and rock ‘n’ roll, by remembering Miss Cornshucks as “the best blues singer” he’s ever heard, “to this day.” She was the first performer he was moved to record, privately, when he was awed by her appearance at a Washington, D.C., nightclub in 1943.

As he recently shared a new listen to “Tenderness” and the 30 other sides Miss Cornshucks recorded (most over 50 years ago, and virtually all unavailable since), Ertegun’s eyes welled up. “That,” he said, surrounded by his memorabilia of Ray Charles and the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin, “was the reason I got into this business in the first place.”

“Little Miss Cornshucks was the most important voice that I’d heard,” says Ruth Brown, the hugely successful singer who helped transform R&B into rock ‘n’ roll in the ’50s, “and, I’m proud to say, she was a big influence for me. There was something really deep in her meaning. That was the kind of stylist that I wanted to be; closing your eyes, you could say just what her meaning was.”

By the late ’40s, Little Miss Cornshucks’ unique style was already a powerful bridge between generations of singing — combining the emotional wallop and clarity Brown recalls, predicting the best soul music of the 1960s — while keeping alive the undiluted sentiment of 1920s Ethel Waters-era vaudeville and torch singing, and working the phrasing and rhythm smarts of 1940s Billie Holiday-era swing for good measure. The continuing shock of that synthesis is a key source of Cornshucks’ power as a vocalist.

“There were three singers of that era who were the best,” Ertegun reflected. “Miss Cornshucks, Dinah Washington, and Little Esther Phillips. But Cornshucks was just so…soulful.”

Little Esther is anthologized; Dinah Washington is even memorialized on a postage stamp. But the story of Little Miss Cornshucks has been a blank postcard in the dead letter office.

The story began in Ohio. By her own testimony to the only one who seems to have asked, the late liner-notes author and Ebony magazine reporter Marc Crawford, Cornshucks was born Mildred Cummings in Dayton, Ohio, “learned to sing at her mother’s knee, and got a great big soul in church.”

Federal records show that she was, in fact, born May 26, 1923. Her own daughter, Francey, adds that Mildred was the smallest, youngest child in a large musical family; she regularly sang spiritual-style gospel with her sisters around Dayton, in a popular local act billed as the Cummings Sisters. A brother was a working musician as well.

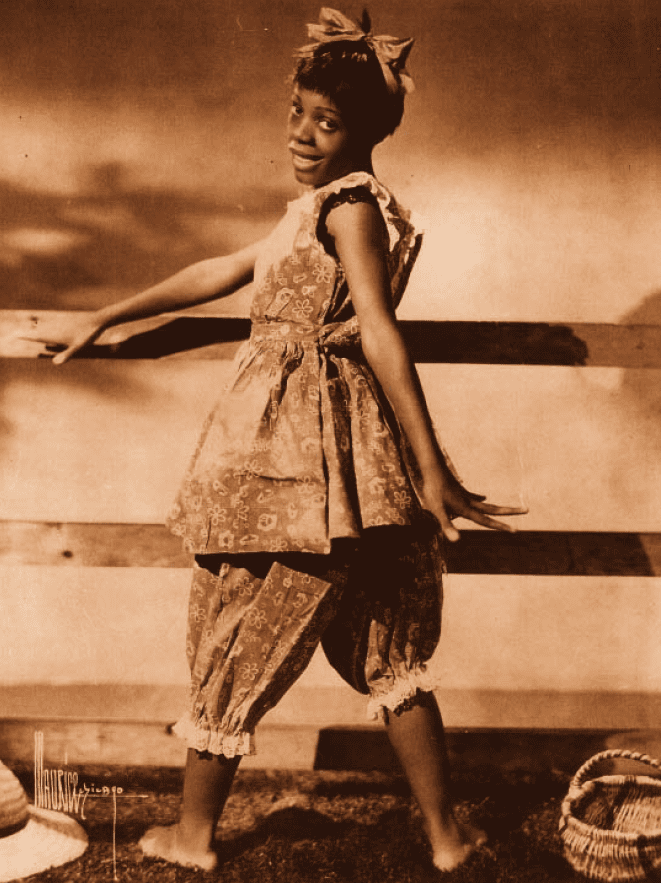

As a teenager in the 1930s, Francey said, Mildred was already stepping out at amateur shows or performing for the family as a single. A lover of poignant, torchy ballads, she began to adopt heart-tugging, down-and-out tramp costumes when she sang them. Briefly, she tried an outfit that presaged street hip-hop gear by decades, but found that her largely black audiences, which consisted of many rural southerners who had migrated to northern towns, seemed to respond best to a touch of country style.

That meant donning a plaid shirt at first, then more, much in the way Charlie Chaplin found his “Little Tramp” character’s suit — piece by piece. Mildred’s mother finally made her the first of the full pantaloons-and-gingham-dress outfits that would be a key part of her emerging Little Miss Cornshucks stage persona. Never finding shoes that seemed quite right, she started taking to the stage barefoot.

A woman who had been promoting gospel acts around Dayton (her name thus far unrecalled) first brought Mildred to Chicago in 1940, solo. Chorus girl Eloise Williams Hughes, now 87, remembers Mildred’s first arrival at Chicago’s famed 1,000-seat Club DeLisa the following year.

“The dance orchestra at that time was Red Saunders’. We just looked up one day and she was there” — with her stage character set and practiced, and an act that quickly grabbed attention. “And she was in love — madly in love with a young man! I mean, as things got going good for her, she bought him a Cadillac, which was something, back in those days. It was the talk of the club!”

The young man, just six months older than Mildred, was Cornelius Jorman, whom she’d met and married back in Ohio, at a very young age. Ertegun remembers him at this stage as a short young fellow in a Wilberforce College sweatshirt; he was from an Indianapolis family that had briefly been living in Dayton.

“She was very conservative at that time; she was in love; she had a kid,” recalls orchestrator Riley Hampton, then an alto sax player with Red Saunders’ popular big band. “When we were at the DeLisa, her husband was always there. He’d have that car out in the alley, and he kept their baby out there.”

That would have been their first child, Francey; two more arrived soon after — daughter Phyllis (whom some at the DeLisa called “Cornshucks Junior”), then son Chauncey. The children were only rarely seen in public, generally staying with the Cummings family in Ohio, particularly as Cornshucks’ husband joined her on the road as her personal manager. Mildred was already soloing in smaller black clubs around the country when Ruth Brown saw her perform at the Big Track Diner in Norfolk, Virginia.

It was on that same 1943 mini-tour that Ahmet Ertegun recorded Cornshucks in Washington, privately, backed by some visiting musicians from Kansas City, including pianist Johnny Malachi, who later worked with Sarah Vaughan. Results of that amateur recording session, Ertegun regrets, are permanently lost.

“When I first saw her,” he recalled, “she sang pretty much the same sorts of things as Dinah Washington — ‘Kansas City’, for instance — but then she also had that song, ‘So Long’.”

Originally the closing theme for bandleader Russ Morgan’s radio show, “So Long” is a ballad of loss and parting that had in 1940 been turned into a modest Ink Spots-style hit by the Dayton-born Charioteers vocal group. By ’43, they were regulars on Bing Crosby’s radio show, and heroes back home. Cornshucks adopted their song and hushed crowds with it.

Little Miss Cornshucks was not just a name Mildred took to match a costume, but a character role she filled. She’d arrive on stage barefoot, her close-cropped but pigtailed wig topped by a little girl ribbon or a frayed, wide-brimmed Huck Finn straw hat, and wearing that ragged, country girl’s make-do dress — usually bolstered by what a Chicago Defender columnist would term “thirtieth century bloomers.” She’d bring a straw basket with her, place it gently at the side of the stage, and watch it get filled with cash as she sang. Sometimes, multiple observers pointed out, it would take two baskets to hold it all.

Her stage manner was summed up smartly in a 1947 ad for Chicago’s famed Regal Theater: The Dynamic Blues Sensation Little Miss Cornshucks, the Bashful, Barefoot Girl with Blues. She was often described not just as a “blues warbler” but as a top “rustic comedienne,” reporters invoking a term then more associated with Minnie Pearl at the Grand Ole Opry than with any jazz/blues act.

Fan Charles Margerum, who much later on would briefly manage her, says, “It’s not so much that she was clowning, or telling jokes, but she did comic things onstage. You know how Fanny Brice would be ‘Baby Snooks’? Cornshucks did that sort of thing.”

She might dance the latest steps out front of the orchestra and chorus girls. “Bashfully” poking her cheek, she might “accidentally” lift her skirt to reveal a pair of famously great legs. She might even stand there picking her nose, “forgetting” where she was. But from that distracted, unkempt little girl would come this no-joke woman’s voice. Riveted audiences would simply not know what was coming next.

Along with modern blues numbers, she’d mix in old torch songs such as “Time After Time” or “Why Was I Born?”, written by Kern and Hammerstein for a 1929 Broadway show. The latter song came to be associated with singers such as Judy Garland (when she donned her down-and-lonely hobo or street urchin characters), or Carol Burnett (as that lonely late-night cleaning lady). These sentimental, comic personifications reached the global stage, and owed more than a little to the “special audience” Cornshucks original.

If, in the wake of those big-time show business performers, the Little Miss Cornshucks character may seem less fresh now, the act was essentially one-of-a-kind in its era. Black women in vaudeville and clubs, even the comics, had almost always emphasized glamour.

There were other startling connections to those later “mainstream” acts as well. “From the time I first saw her, she sat down on the edge of the stage and sang right to you, all of that, long before Judy Garland did it,” Ruth Brown points out.

Garland would adopt the same stage tactic at her famed concert at the New York Palace theater in 1951, and reprise it in the film A Star Is Born — which, provocatively, also featured her in a Cornshucks-like country street girl outfit dancing along with black kids. (Garland had frequented the very clubs where Mildred appeared in the ’40s, and they eventually shared a number of direct Hollywood ties.)

“Cornshucks’ schtick was trying to get to you,” Margerum recalls. “She could just mesmerize a certain type of crowd.” That type of crowd was most prevalent in northern cities, especially in Chicago, where masses of rural southern Afro-Americans had migrated, searching for work, beyond the reach of segregation by statute.

Many in her urbane, largely black club audience had some far-from-urban memories, whether firsthand or received from parents — memories reawakened by performances of a shy, funny, but vulnerable country woman-child you wanted to protect, who, like Garland or French street heroine Edith Piaf, had somehow been badly hurt.

By 1945, in that town, Little Miss Cornshucks was becoming a star.

Cornshucks was featured at Chicago’s posh Rhumboogie Club, owned by heavyweight champ Joe Louis, where jazz band conductor and arranger Marl Young worked with the likes of T-Bone Walker (on guitar) and Charlie Parker (on sax). When Young moved over to the top-of-the crop Club DeLisa to conduct the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra there, that already familiar haunt became Cornshucks’ regular home base, for years to come.

The DeLisa was nearly as famed in its day as New York’s Cotton Club, but with an audience that, by the ’40s, was more racially integrated. There are photos of everyone from Gene Autry and Louis Armstrong to John Barrymore hanging out there. Since the price of admission was as little as the cost of “set ups” (glasses and ice, maybe with a mixer) and you could choose to bring your own, the sophisticated street really did mingle with the elite — black and white. For many, it was also the sort of place where, as it’s often put, “you could buy anything you wanted.”

In 1945, seasonal themed revues at the DeLisa would run all night, featuring celebrated dancers such as the Step Brothers or Cozy Cole, comics such as George Kirby, and top-line orchestras. One who played behind Cornshucks regularly in the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, keyboardist Sonny Blount, would have the ongoing chance to observe these extravaganzas and Mildred’s character-based headline act closely. He must have learned a lot: He eventually produced more modernist revues of his own and transform himself into the character called Sun Ra.

Cornshucks regularly delivered the rhythm numbers the times demanded; raucous jump blues was king. But it wasn’t everything.

“Mike DeLisa, the club owner, wanted her to do those blues, but we had that slow ballad ‘So Long’ that she did, and I would call the number,” Marl Young remembers. “He’d come rushing up the aisle to say, ‘Don’t do it!’ and I’d just turn my head like I didn’t hear him. When she took that stage, boy — that was it! Everybody stopped and was quiet, listening and looking.”

By the following year, Young and his brothers were running a short-lived record label, Sunbeam, among the earliest to have been black-owned, with Miss Cornshucks as their star act. The half-dozen sides she cut there in 1946 document a varied, experimental recording act in the making.

If some of these first records, though skilled, are very much of their moment, with noticeable Billie Holiday influences, others startle.

“When Mommy Sings A Lullaby” shows Cornshucks’ characterization skills, sounding alternatively like the joyous remembrance of the child and of an assuring mother — on the same record. Margerum accurately describes that chameleon-like quality captured on these lavishly orchestrated 78s: “She had a good voice — but not only a good voice; it didn’t always show the same way.”

Her affecting signature tune “So Long” was a regional hit, Sunbeam’s largest; poet Langston Hughes would cite this orchestral version as among his favorite jazz recordings of all time. Arguably, the number would work even better on a simpler 1951 Coral Records version.

The most remarkable of the Sunbeam sides is “I Don’t Love You Any More”, a swinging upbeat blues co-written by Cornshucks and Young. The lyrics and music taunt the abusive man who has tossed her out into the street, left her drifting door to door — and Cornshucks turns it, in a moment of self-discovery of newfound freedom, into a triumph of female independence.

In her own life, however, Mildred Cummings Jorman’s blues were not so handily beaten.

She suffered from growths in her nasal cavity, leaving the impression on several recordings that she may have had a bad cold. She received regular injections to treat them, fearing that having the growths removed would alter her inimitable voice. She also suffered from severe asthma; there were times they had to rush her from dusty stages right to a hospital, because she simply couldn’t breathe.

Back in Ohio, other aspiring performers in the Cummings family were increasingly jealous of young Mildred’s growing success, even as she was essentially supporting them with whatever money she earned, daughter Francey says: “They were taking advantage of her — and they weren’t the only ones.”

Meanwhile, the once-proud husband Cornelius, functioning as her manager, was described by some who met him first in the mid-’40s as someone “to be avoided.” More than one observer present at that time suggests strongly that, like many around the 1940s nightclub scene, he’d become involved with drugs on some level. Friends of Mildred from Chicago state flatly that he’d been unfaithful, and was now “just showing up to take some money and go.”

Their daughter Francey does not dispute that scenario. “Well, they were very young people — and flighty. Just out there,” she says, “and he was even more out there than she was! He was just young and wild, that’s all. And they were very off and on with each other.”

As Eloise Hughes, the last surviving DeLisa chorus girl, put it, “She’d been so much in love with him, and he was womanizing. I think his cheating on her was what set her on her downfall.”

With the marriage over for most practical purposes, Cornelius returned to Indianapolis. Under the pressure, even friendly observers suggest, Mildred began to drink too much.

“She began to turn,” says arranger Hampton. “It had to do with her family and the divorce from her husband. She was drinking a lot and lost control of herself.”

The immediate family says that people exaggerated Mildred’s state; that she never, for instance, really suffered from what a common street diagnosis termed “mental problems,” that these experiences even toughened her. In any case, it was in this troubled context, ironically, that the most prominent phase of Little Miss Cornshucks’ professional life bloomed.

While the fledgling Sunbeam label had to be sold off in less than a year, the records cut there added to her fame nationally. With Cornelius moving to the background, Arthur Bryson, described at the time as “the one Negro full-time theatrical agent on Broadway,” became her working manager. A 1948 report in Color magazine says Cornshucks had already “had a telling effect” on Bryson’s growing business, and shows her autographing new reissues of her Sunbeam sides on the Old SwingMaster label, as fans — black and white — await their copies.

Mid-’40s reviews report smash shows in Detroit, where she replaced jump blues star Wynonie Harris at the Frolics Bar; success in New York City clubs such as the Baby Grand; and across the whole so-called “Around The World” tour of major urban black theaters: the Washington Howard, the Philadelphia Earle, the Chicago Regal, the New York Apollo.

As Lee Magid, producer at key jazz and R&B label Savoy Records, told Arnold Shaw for his 1978 book Honkers And Shouters, “that little black chick with two buckets and pigtails would come out in the Apollo Theater — in rags — and sing her ass off.”

It was on one of these trips to Detroit, show dancer Henry “Henny” Ramsey says, that he and Miss Cornshucks met and began traveling together for several years. The children remained with her family in Dayton. Ramsey describes their relationship as a brief, de facto marriage. A good amount of their time was spent in her new home-away-from-home, the bustling, lively, late-’40s jazz and R&B scene around Los Angeles’ Central Avenue.

Cornshucks headlined at the Last Word Room, played one-nighters with acts such as the Joe Lutcher Jump Band and Joe Liggins, and starred at the top Central Avenue venue, the Club Alabam, along with T-Bone Walker and Wynonie Harris, and comedians Redd Foxx and Moms Mabley. The music, built on honking saxes and electric guitars, sparked hot new dances and attracted Hollywood stars who came to take in the moves.

L.A. jump king Johnny Otis has described the Club Alabam scene thusly: When two main bands, his own and Harlan Leonard’s Kansas City Rockers, backed singers such as Cornshucks, you “could see the music that was to be named ‘rhythm and blues’ taking shape.”

Cornshucks’ live performance peak was a set of shows in early 1948 in downtown Los Angeles at the elaborate, 2,200-seat Million Dollar Theater, a former movie palace then hosting acts such as Nat King Cole and Artie Shaw. Cornshucks was advertised as “the new look in comedy” and referred to in an L.A. Sentinel report as “a rustic comedienne as good as Judy Canova.” Comparisons to Canova — popular, energetic white country girl entertainer — were usually reserved for Minnie Pearl. Cornshucks’ stand at the Million Dollar Theater set house records.

Her reputation as a comedienne bore additional fruit when in November 1947 she was cast in Campus Sleuth, a B-movie made at Monogram Pictures, home of the Bowery Boys and Charlie Chan. One in a series of cheap, hour-long musical mysteries involving the Teen Agers (a set of young, adventuring friends including Freddie Stewart, June Preisser, and the future Lois Lane of TV’s 1950s “Superman” series, Noel Neill), this forgotten film also featured swing band leader Bobby Sherwood, Judy Garland’s brother-in-law.

The film, released later in 1948, has proven impossible, thus far, to find, missing even from the Library of Congress and university Monogram Pictures archives. But a shooting script shows that Mildred Jorman (billed as playing the character Little Miss Cornshucks) appeared later in the picture, running a haywagon ride on a campus reunion weekend with her “boyfriend,” singer Jimmy Grissom. (Grissom, who, like Mildred, recorded for Miltone records at that time, would eventually sing with the Duke Ellington Orchestra.)

Cornshucks, in full character regalia, has comedy bits, cries when the boy hides from her in the woods (her daughter recalls that she could cry “on a dime”), then sings (a handwritten note on the script indicates) a new self-penned number she would soon record, “Cornshucks Blues”.

Meanwhile, her own dramas had hardly ended under the California sunshine. They took her, once, to the outskirts of a still obscure Las Vegas, Nevada.

“Her husband kidnapped her out there one time,” Henny Ramsey says. “I was sitting at home waiting for her to come home from the movie studio, and when 6 o’clock come, I said, ‘Where’s Shucks?’ The phone rang, and she was saying, ‘Baby…Cornelius just said “Get in the car,” and drove me clean to Las Vegas!…And he put me out and took the money and the car.’ He just left her in the mountains out there…in the desert.”

Inevitably, with her rising fame, new recording opportunities followed, all in Los Angeles.

The first sessions, in May 1948, were at that little Miltone label, under the direction of tenor sax player Maxwell Davis. Today, Davis is called the father of west coast R&B, the man behind hits by Percy Mayfield and B.B. King as well as early recordings of Charles Mingus. He cut nine sides at Miltone with Cornshucks — including the memorable ballad “In The Rain” (later covered by Ruth Brown), a sweet turn on the standard “He’s Funny That Way”, and excursions into straight blues, such as the “Cornshucks Blues” number from the Campus Sleuth movie.

The Miltone 78s show Cornshucks in complete command vocally. In light of the senseless “divamatic” oversinging so prevalent in pop, country and R&B today, it’s downright bracing to hear the ease and simplicity with which she can make clear both acceptance of love and its loss.

On these sides she sings soft and slow, without frills, painting a picture of the situation, until — just at that right moment — there’s a sudden cry or a stern warning, completing the emotional picture and bringing us along. Her ability to hold and then stun listeners in a single number, which mesermized live audiences, is detectable on record as well.

The Miltone singles were credited to “Little Miss Cornshucks with The Blenders” — the Blenders being a house band built around musicians who played with Roy Milton’s hit-making Solid Senders. At least one side, the ballad “Keep Your Hand On Your Heart”, was arranged by pianist Calvin Jackson, who would later ghost-orchestrate more than a dozen movie scores for MGM, including Meet Me In St. Louis, starring Judy Garland.

Cornshucks’ homecomings to Chicago were triumphs now. Defender columnist Lou Swarz gushed, after the Million Dollar Theater triumph, that agent Arthur Bryson was “being offered heap much” for her to make a return engagement to an unspecified Chicago venue: “No wonder,” he added, “with her act being so unique. Watch the climb to stardom of Little Miss Cornshucks!”

Ramsey remembers a series of unchronicled shows Cornshucks did out on the road around this time with the old vaudevillian and bandleader Ted “Is everybody happy?” Lewis, including a show at the upscale Los Angeles club Ciro’s. “She had them white people cryin’ out there, every time she sang,” he says.

Such a racially integrated act would have been unusual. It’s also suggestive that Lewis frequently sang “She’s Funny That Way” himself, and that he had been an early performer of a number Cornshucks soon adopted to extraordinary effect: “Try A Little Tenderness”.

Back in California, at Aladdin Records in 1949, she waxed a couple of new tunes as Miss Cornshucks & Her All-Stars. “Waiting In Vain” is among her most expressive recordings, featuring close vocal give-and-take with a deep, aching sax that is very likely Maxwell Davis’ again; he was the key producer there.

Cornshucks’ exemplary emotional and vocal control is also evident on “(Now That I’m Free) You Turned Your Back On Me”, in which she pulls off a challenging feat: She rides the upbeat feeling of just getting free, but still cues us in on the pain she feels when spurned by the second lover supposedly waiting for this moment.

The song may or may not reflect the fact that her relationship with Henny Ramsey was about over. Young daughter Francey, home in Dayton, was unaware of it at the time, but in retrospect is surprised it lasted even that long, since after her marriage troubles, “Mom never got that close to anybody,” Francey says.

Ramsey’s own perspective: “Well, she started drinking that whiskey, and I couldn’t live with it. If she’d see me even talkin’ to a woman, she would come up and start fighting. I had to stand at the end of the stage until she got off, so she could see me! She was so sweet when I first met her — but it was that whiskey, man.”

In the summer of 1950, Cornshucks was featured in an Ebony magazine cover story that focused on how popular jump blues singers had become. She was included right along with the biggest names of the era — Arthur Crudup, Ivory Joe Hunter, Roy Brown, and Amos Milburn. Professionally, at least, things were rolling.

The small-group approach used effectively at Aladdin set the stage for sessions at Coral Records in 1950 that featured the best backing band she’d ever have, under the direction of swing legend Benny Carter.

“Papa Tree Top Blues”, among the first sides Cornshucks cut with Carter at Coral, is one of her most striking extended blues turns. They also recorded, with bright, positive results, Carter’s pre-rock composition “Rock Me To Sleep”; it’s probably the best uptempo number in her catalogue.

Union contract records show that the previously unnamed jazz musicians on these sides, whom even Benny Carter himself can no longer identify by ear or memory, included such busy Central Avenue talents as Bumps Meyer, Que Martyn and Charles Waller on saxes, Eddie Beal on piano, and Mingus’ teacher Billy Hadnott on bass.

Recorded at Coral’s state-of-the-art studio on Melrose Avenue, these sides show just what Little Miss Cornshucks could be — singing like one smooth, vibrating violin, then suddenly shaking you like a horn. These, and the follow-up singles cut there in 1951, for which no session notes survive, were the best records she ever made.

They included the definitive recording of “So Long” — never more rueful, full of surprising syllable bends, stretches and trills, yet utterly direct; the blues “I Lost My Helping Hand”, in which she handles great vocal and emotional ranges in tandem with Carter’s honking sax; and, so notably, that record which introduced “Try A Little Tenderness” to the world of soul.

But if this was the working peak for Mildred Cummings Jorman and her Little Miss Cornshucks show, a series of circumstances and limitations would make 1951-52 the de facto end of her near stardom.

Back in Chicago, Delores Williams, a young niece of blues legend Memphis Minnie, was dressed up, by owners of clubs that Cornshucks had played, in an outfit indistinguishable from hers — and billed as “Miss Sharecropper.” Confusion was inevitable, and deliberate. Miss Sharecropper’s handlers even recorded “So Long” with her for National Records in 1950.

In New York, Ahmet Ertegun and Herb Abrahamson had started up Atlantic Records in 1948, on a $500 loan. While they remembered Cornshucks fondly, as Ertegun explains now, “We didn’t know then even where to find her. And at that time, we didn’t have money for things like finding people!”

They did know a young singer in town named Ruth Brown, who would deliver such a string of early hits with them that Atlantic is often called “the House that Ruth built.” What’s generally forgotten is that Miss Cornshucks provided some of the blueprint for that house, since the first, key smash Brown hit was an outright copy of Cornshucks.

“You’ve heard Ruth Brown’s record of ‘So Long’?” Ertegun asks. “Well, that doesn’t even sound like Ruth; she sounds like a different singer! And it doesn’t sound like any other recording she made ever after, either. We signed her at first because she could sound like Cornshucks!”

Brown, charming in her candor, is even more blunt: “I stole that from her! It was a big hit for me — and it should have been hers.”

Not one of the labels that handled Miss Cornshucks ever furnished the kind of ongoing support someone who could be so delicate surely required.

Coral/Decca didn’t back her for long, but she was contracted there just long enough to miss a potentially bigger opportunity. In 1951, she was singing with Maurice King’s band at the Detroit Flame Show Bar when Okeh/Columbia Records producer Danny Kessler caught her act. He’d tell Honkers And Shouters author Arnold Shaw, “I flipped over her, but found that she was unavailable.”

A white boy who had seen Cornshucks perform in Chicago, and had developed a similarly dramatic way with a ballad, followed her onstage that night. Kessler signed him instead, and they would be pushing out hit after national hit together just a few months later. The boy’s name was Johnny Ray. (Legendary San Francisco critic Ralph J. Gleason later underscored that Ray’s famed rock-predicting emotional style was, in fact, influenced heavily by Cornshucks.)

Mildred’s own recently burgeoning career then took a series of hard hits in rapid succession.

Miltone’s Warr Perkins and William Reed put out some sweet 78s with amusing cartoon labels that collectors love, but they were more interested in selling off record rights than in actually pushing discs. The Miltone sides were delayed, then sold to Aladdin, Gotham and Deluxe Records — in some cases to all three, practically at once. These labels began stepping on each other’s release dates, as announcements in Billboard indicate. The generally positive Billboard previews of the records were not enough to help. And Cornshucks would not have been paid for those resold sides at all.

A would-be “manager,” claiming to represent Cornshucks, put come-on announcements in the trade papers and Afro-American weeklies, detailing an enticing upcoming tour of Latin America that never occurred.

Marl Young, who had moved to California and become a successful conduit for consolidation and racial integration of the Los Angeles musicians’ unions, calls the parties from Miltone “crooked S.O.B.s.” Trade papers reported that these parties were being sued by Miltone founder Roy Milton for record bootlegging, even as Mildred began recording. Young adds, “She was not a sophisticated, educated woman; she was having all sorts of trouble then, being taken advantage of.”

It got worse. A telltale sign is the noticeable downturn in her appearances during 1951-52. Just as the multi-label records were tumbling out, background personal stress was coming to the foreground. Word got around that the rising star had suffered a “nervous breakdown.” Ertegun recalls, for instance, in explaining why Atlantic never signed Cornshucks: “Well, then we heard that she had mental problems.”

In 1953, Atlantic instead signed the rival known as Miss Sharecropper, a talented singer who was eager to drop the imitative persona. She proceeded to record under a new name — LaVern Baker — and subsequently became the first rock ‘n’ roll queen, with hits such as “Tweedlee Dee” and “Jim Dandy To The Rescue”.

Rather suddenly, there was not much interest in performers who didn’t fit this new “rock ‘n’ roller” model; old-style nightclubs were closing. This shift could only have added to Little Miss Cornshucks’ consternation.

“With her type of entertainer, performing’s a spiritual thing,” Charles Margerum suggests. “When they’re at their peak, it’s like a high — and when they shut down, they don’t understand that it’s really shut down. The times changed, and she wasn’t really akin to that new style coming in.”

Mildred Jorman was 39. Some who began to lose track of her amid the emergence of rock ‘n’ roll have long believed that she quit show business at this point, debilitated and frustrated. But that’s just not so.

Mildred did get out of Chicago; her daughter Francey confirms that she moved to nearby Kenosha, Wisconsin. She stopped touring, and no one was recording her. But frequent ads in the Chicago Defender and elsewhere verify that she regularly returned for appearances.

The venues were smaller, but, not at all bad. She appeared in Chicago at Little Joe’s High Hat Lounge, at the Flame Show Lounge with singer Jo Jo Adams (who reportedly was briefly her boyfriend), and even back at the fading DeLisa. On one occasion, she sent Francey, then a teenager, out in the Cornshucks costume to confuse the regulars; both mother and daughter wound up onstage together, along with a visiting Pearl Bailey.

She appeared in revues at the Crown Propeller Lounge hosted by beloved Chicago DJ McKie Fitzhugh, sometimes sharing stages with blues shouter Joe Williams. There was a notable stand in 1956 at the Budland club with the King Kolax band and the Delta Rhythm Boys; Cornshucks also appeared at Budland in a “Battle of the Blues” with two fine Texas bluesmen — pianist Floyd Dixon and guitarist Clarence Gatemouth Brown.

There were also, increasingly, unscheduled “bad day” appearances that were a little bizarre. Denizens of South Side clubs remember Miss Cornshucks showing up where she wasn’t booked and wandering onstage singing, interrupting ongoing acts.

“We’d be in a place, playing, and she’d come by and do some nutty things,” musician and local historian Charles Walton recalls. “First thing she’d do is throw her wig at you. She’d take her dress over her head…all kinds of nutty things.”

Ruth Brown recalls another mid-’50s incident. “I was playing in Chicago at the Crown Propeller. We’d been friends, but she came in and sat down at the bar, and just for that moment she got real angry at me, because I’d sung her song ‘So Long’ — and she just twirled her wig on her finger and threw it right at me!”

In 1958, Cornshucks showed up back in Los Angeles, when a new turn for her career looked possible. Old backer and friend Marl Young was now an arranger/conductor at the Desilu studio and was soon to become musical director for Lucille Ball’s TV show. They brought Miss Cornshucks there for a possible non-musical movie role, and called in Young to work with her.

“She was supposed to speak some lines, but she had trouble memorizing them. They thought I could help, because she trusted me. It didn’t help, though — and I never saw her again after that.”

Soon after, “drifting blues” master Charles Brown, blacklisted from major venues by the union for “skipping a gig,” found work outside of Cincinnati and brought Mildred along.

“I had to go to Newport, Kentucky, and work with the gangsters there; that kept me going!” he told a Cincinnati Post interviewer. “I had in Little Miss Cornshucks, and Amos Milburn. I was bringing in all the people who were having a hard time.”

But just a little later, in 1960, times for Miss Cornshucks suddenly looked a whole lot better.

As she had done in many places before, Cornshucks wandered into Chicago’s spacious Roberts Show Lounge one night. Charles Margerum, who was temporarily managing shows there under contract, recalls, “She was all screwed up drinking, getting into crying jags. She just walked up on the stage, unannounced, but people knew her — and she hushed that crowd!”

This time, instead of tossing her out, they booked her for a week, in a show with young comic Dick Gregory as MC. On the last night, as both Margerum and the late writer Marc Crawford have related, among the curious who showed up to see her most publicized show in nine years was Rock and Roll Hall of Famer Ralph Bass.

Bass had known Cornshucks back on Central Avenue in her Los Angeles days, and had since become a major record producer — he was the hipster who signed James Brown to King Records.

“She was sitting there on the edge of the stage singing, and Ralph said she still sounded good,” recalls Margerum who was now representing Cornshucks despite misgivings about her condition. He suggested to Bass that it might be really interesting to try recording her with strings.

That must have struck a chord. Ray Charles’ “Georgia On My Mind” was a string-laden hit that year, RCA was trying out strings with Sam Cooke, and they had just started experimenting with strings where Bass was now musical director –the core Chicago blues label, Chess Records.

Word that Cornshucks was going to record again caused a considerable stir in Chicago jazz and R&B circles. Working singers such as Lorez Alexandria showed up at the October and November 1960 sessions just to watch and listen. Bass set about re-recording some of Cornshucks’ most celebrated numbers in an updated context, with strings, adding a handful of R&B numbers from the rocking ’50s style she had essentially missed.

Miss Cornshucks told liner-notes author Crawford about confronting that “new music” in a revealing direct quote:

“I was nervous and scared the day I walked into the recording studio…I’m no rock and roll singer. Would the people like me? It took a while to get straightened out. Finally, I decided just to go on and sing what I felt, do the best I could…What else was there to do?”

According to Margerum, who was present at the sessions, technicians loved the voice they heard, finding they didn’t have to adjust controls when she performed — nearly alone with a microphone. Neither the group — piano, guitar, bass and drums, located elsewhere in the studio — nor anyone else (none of the string session players) were there to interact with Miss Cornshucks at all, even for her to hear.

Bass was using the newfangled technique of adding on the strings later — no doubt strange for a nervous returning singer of the ’40s who’d worked best with close audience and musician contact. The strings were actually arranged by the same Riley Hampton who had played behind her at the DeLisa years before.

“I had rhythm and strings on her session, as best I can remember!” Hampton says now, from retirement in Little Rock. “At that time, I used from seven to nine strings — violins, and two violas and a cello. I did a lot of that stuff with Etta James, too.” One famed example, recorded not long after these sessions and patterned after them, was James’ classic At Last.

The resulting Cornshucks LP, The Loneliest Gal In Town, was released in mono on Chess in early 1961. In the big color cover photo, Miss Cornshucks sits on a railway trunk in full character regalia, screaming red dress, straw hat, pantaloons and all.

The songs with strings are all bunched together on one side, with the small group numbers on the other. The album includes re-recorded versions of “So Long”, “Try A Little Tenderness”, “Why Was I Born?” and “You Turned Your Back On Me”. (The remakes, it must be noted, are inconsistent.)

Her phrasing and attack are still there, sometimes touchingly so, despite the perceptible aging. The voice has coarsened and lowered; you can catch her struggling to reach some notes, and there are oddly strained enunciations and tics in phrasing — perhaps an effort to simulate some of rock ‘n’ roll’s more mannered styles, in a sort of “Little Anthony” mode.

The best cut on the LP may well be “The Lonesomest Girl In Town”, a slow old Tin Pan Alley tune that shows the singer’s acceptance of her own obituary, in a dramatic, desolate, half-talked reading. Some of the new R&B numbers actually fare relatively well, too — a version of Johnny Ace’s “Never Let Me Go”, and “No Teasing Around,” which clearly anticipates soul ballads still up the road. The “Tenderness” remake approaches outright crying, ending in a dramatic “try a little…try a little” build that specifically predicts later Stax-Volt drama.

“After the record was made,” says Margerum, flatly, “I sent her to a couple of places, but I would have had to go with her and monitor her all of the time. She couldn’t make it on her own. Wherever she would go, she’d get some booze, and once she got into booze — well, I had other clients.”

Chess put a couple of the new R&B songs on a single — “No Teasing Around”, penned by Billy the Kid Emerson, backed with “It Do Me So Good”, by Emerson and Willie Dixon — but the 45 didn’t click. Some months later, Margerum was sure he heard a different Cornshucks single on the radio.

“This new record of ‘Try A Little Tenderness’ came out, with strings, and I thought, ‘Yeah; there it was!’ The guy on the radio said, ‘You’ve got to hear this!’ And he just played it over and over. And then he said, “That, ladies and gentlemen — was Aretha Franklin.”

Aretha’s string-laden version of “Tenderness”, lavishly produced by Bob Mersey in April 1962 and among a handful of Franklin singles released by Columbia Records that year, shows Cornshucks influences that are hard to miss — from the opening “I may be weary,” to the mannered enunciation of many of the phrases, to the emphasis on certain emotional points. It got heard then — it reached the Billboard pop charts — and has been in print most of the time since. And it overshadowed what had come before.

There was no new Cornshucks “Tenderness” single from Chess. Nothing much happened with her only LP, and the disappointment must have been overwhelming.

Mildred Jorman would now truly begin to disappear.

Dancer Lester Goodman, returning to Chicago after years on the road with the traveling Ted Steele Revue, renewed his friendship with Cornshucks at this time. Goodman says she had just about stopped performing late in 1961, not that long after the Chess LP’s release. After a while she moved back to Chicago, staying at a theatrically-oriented South Side hotel.

Her last advertised appearances included a July 1963 show at jazz room McKie’s Lounge — side by side with Ruth Brown, now some years past her hits herself, and well ahead of an eventual comeback.

A Halloween show at the Golden Peacock in 1966 put Cornshucks on the bill, very possibly for the final time anywhere, with West Side guitar stylist Eddie C. Campbell and his band. She employed a last vocal turn that sounds like an extension of some rhythmic talk heard on the Chess LP — perhaps borrowing a tactic from Ted Lewis, who’d always used dramatic patter.

“She was a very sweet lady. She would sing a little bit and then she would talk a little bit — just like poetry,” Campbell recalls. “Was she good? Yes, she was; she had that beat and was good and all — even though her voice wasn’t there.”

Campbell and Cornshucks were both being handled, Campbell notes, by Jay Banks Delano, who ran the tiny R&B labels Delano and Hawaii and also specialized in booking acts “who’d lost a lot of their money,” Campbell says. Campbell recorded for them; Cornshucks evidently didn’t.

Lester Goodman ran into her a while later: “She told me that she’d then gone into the church, was singing only in a church, and couldn’t be hired anymore.”

Daughter Francey simply says that her mother didn’t perform again, anywhere, save for the funerals of friends. But a curious Cornshucks coda occurred in 1975.

The late Jimmy Walker, a fabled boogie-woogie pianist very much up in years, but still active, was in a South Side supermarket when he spotted Cornshucks, shopping for groceries. He had instant visions of setting her up for a comeback — live appearances, even recording again. He invited her to his nearby basement rehearsal space to see what could happen.

Bassist/engineer Twist Turner recalls: “The following week, Miss Cornshucks showed up at our rehearsal, wearing regular street clothes. She brought a bottle of white port and a package of Bugs Bunny brand lemon flavor Kool-Aid in her purse. We played a couple songs while she and a friend stood around and drank the port.

“I was really interested to hear her sing, excited about being a part of her comeback. Jimmy gave her the mike, but the next thing I knew she just snatched off her wig and threw it on the ground. She did sing a little, baldheaded, but she just couldn’t get it together to perform.”

Mildred did show up again, with startling effect, at the 1980 Chicago wake for the famed “sepia” dance troupe producer Larry Steele, with whom she had appeared years before. Much of the black show business community had gathered to memorialize Steele; the A.A. Raynor Funeral Home was packed. Lester Goodman relates what happened.

“She just walked in, from the back — already singing. She came all the way up the side aisle, singing. It could have been her song ‘So Long’…”

“So long, hope we’ll meet again someday…”

“…and she finished it just as she reached the funeral bier at the front. The place was hushed. It was such a surprise that she was there; she had faded out, you know.”

Longtime Living Blues magazine editor and Chicago resident Jim O’Neal ran into Little Miss Cornshucks face-to-face in March 1980, while visiting the same South Kenwood Avenue apartment building in which she lived. He tried to arrange an interview, but it never materialized. The generally reliable Living Blues erroneously reported the death of Little Miss Cornshucks, in a passing reference, in 1985, apparently based on someone’s misunderstanding of a report that she was now “gone” from the city. Around that time, Lester Goodman attempted to reach her at the Chicago resident hotel where she’d last stayed; he, too, was told she was “gone” — perhaps back to Dayton.

And that, her family confirms, was the sad-enough truth: Mildred Jorman continued to live alone in Dayton for many years, unrecognized, doing “not very much.”

In the early 1990s, after suffering a stroke, Mildred moved closer to Francey and surviving Jorman relatives in Indianapolis. (Cornelius had passed on in the ’70s.) Her health worsened, and further strokes followed. She joined other family members in taking Bible Study classes with the Jehovah’s Witnesses; she was taking a class over the phone when she suffered a final stroke, and her last words came during that conversation.

She was, in those last years, Francey reports, saddened to be forgotten, resentful that others had capitalized on musical breakthroughs she knew she had made. She died in Indianapolis, at the age of 76, on what in her day they had called Armistice Day — November 11, 1999.

It went unnoted.

ND contributing editor Barry Mazor thanks the dozens of direct witnesses, record collectors, and period specialists who helped make this report possible, over the more than two years that it’s been in the making — especially fellow music researchers Nadine Cohodas, Robert Pruter, Charles Walton and Alan Balfour, who suggested directions that proved especially important.