Hello Stranger from Issue #13

It took me a few days to notice the parallel, when I heard around mid-October that Butch Hancock was reviving his old self-run record label, Rainlight, to release his latest album. A little over a year ago, Butch left the rat race behind, leaving the daily operations of Lubbock Or Leave It — the art gallery/record store/tape duplication center/etc. that had been his home in downtown Austin during the ’90s — in the capable hands of Barbara Roseman. Destination: Terlingua, deepest desert West Texas, on the banks of the Rio Grande, population about a couple dozen.

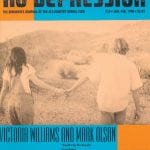

Meantime, back in July I had run into Mark Olson and Victoria Williams at a show in Toronto, opening for Blue Rodeo. Olson kindly passed along to me a tape of some songs he’d recorded recently in his living room at their house in another desert town, Joshua Tree, on the edge of the Mojave in Southern California. As he and Victoria and fiddler friend Mike “Razz” Russell talked about it, they seemed to decide right then and there that the thing to do with this tapes was to just release it themselves, sell it out of their house through their P.O. Box in Joshua Tree.

The way Hancock and Olson got to the same place was different, of course. For Olson, it seems a situation brought on by his bitter experiences with the music business during his days with the Jayhawks. Hancock, on the other hand, has been here before, having issued his first several albums on Rainlight in the ’70s and ’80s before giving the record industry a try with releases on Demon (U.K.), Virgin (Australia) and Sugar Hill (U.S.). His conclusion, it seems, is that he had it right all along when he decided to make a go of it on his own.

Certainly, the results bear out both Hancock and Olson artistically. While Hancock hardly ever catered to commercial considerations even with his Sugar Hill albums, his return to totally solo acoustic presentation of his songs seems somehow the most natural and appropriate direction for him to have taken at this point in his life. Listening to You Coulda Walked Around The World here at the headquarters at 2 a.m. on drop-deadline night, all suddenly seems right with the world, even after a long weekend during which everything seemed to be going wrong. Sometimes, having been dislocated from Austin for more than six years now, I get to wondering if there is such a thing as “home” for me anymore; but when I hear Butch Hancock’s rough, warm singing and sturdy, simple strumming, I am home. His songs are home.

The Original Harmony Ridge Creek Dippers, meanwhile, has been a gentle friend for half a year now, ever since Olson gave me that tape back in July. Certainly this isn’t what “the industry” would have wanted or expected from him — and that’s just fine, because when it comes down to it, it really ain’t that hard to just decide you’re gonna make the music exactly the way you want to. Sell it yourself, if you want to. Live in the desert, if you want to. Otherwise, what’s the point?

A year ago I was filling this same space with words about Townes Van Zandt, who died Jan. 1, 1997. When I think of artists who understood art for art’s sake, I still think of Townes, more than anyone else. And I think of him often.