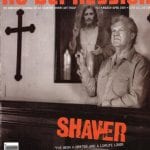

Eric Taylor – Deep dark soul of the sweet sunny south

Townes is dead and Guy is co-writing these days. Eric Taylor is drinking Hennessy cognac, watching people watch him, then flipping through a black notebook where he keeps the songs.

It’s Anderson Fair in Houston, or the Sandwich Factory in Spartanburg, South Carolina, or a house concert in Jackson, Tennessee, or Eddie’s Attic in Atlanta. And people are waiting on him. Maybe someone works up the nerve to request “Deadwood, South Dakota.”

“‘Deadwood’,” he says. The title is “Deadwood.” Nanci Griffith recorded it and called it “Deadwood, South Dakota,” and Eric says her take on it was top-dollar but the title is “Deadwood.”

Then he flips some more, puts down the drink, fingerpicks piano intervals on his guitar until he feels like singing, then finally begins the story: Well, the good times scratched a laugh from the lungs of the young men…

Nanci Griffith and Lyle Lovett and Joan Baez and June Tabor. Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt and Houston, Texas. And none of this matters a bit, as the story unfolds.

And it’s not the story, it’s just one of them. There’s a black notebook full of them. Griffith says they’re great, and she’s not even married to him anymore. Lovett learned a lot of them, and a lot from them. Baez called to get the chords to “Strong Enough For Two” right, Tabor recorded two of them, and Clark and Van Zandt…well, they were around. Hell, they were the kingpins around Houston, at least when Lightnin’ Hopkins wasn’t in the room. And none of this matters a bit, as the story unfolds. Man, Eric Taylor will get on with a story.

He’s got eleven of them on his new Scuffletown album (out March 20 on Eminent Records), though two of them are Townes’. One’s about a family that sticks together until the well comes in and allows them to disperse. Two are about murder and escape. Another’s about a Southern albino. They’re all good, and that’s nothing new. Eric Taylor’s been getting on with stories for years.

Eric Taylor: I was probably about six or seven, in Greenville, South Carolina. One night, I was standing at the end of the street, along with many others on the block, looking into the night sky at a beautiful moving curtain of colors. There were obviously some weird atmospheric conditions allowing a glimpse of the aurora borealis. I had no idea what it was at the time, but I heard someone say that it was the Northern Lights. Northern Lights? I remember thinking, “How come the Yankees get all the good shit?” Mickey Mantle and the Northern Lights. Fuck me runnin’.

Eric Taylor was born. The year was 1949, and the city was Atlanta. He soon moved to Greenville, spending formative years learning things he later dismissed.

“My old man was a tried and true racist,” he said. “He would have been a tried and true racist if he’d lived in Boston, just like the tried and true racists of Boston would be if they lived in South Carolina. Certainly, he was consumed with it, and he demanded the company of his family. My old man was not about the South, but he liked thinking he was. I stood and postured along with the rest of the children, and used ‘nigger’ to define any and all that confused and angered me. When I grew out of that, as many do, the seeming separation was personal, familial and lasting.”

As a child, Taylor played Yankees and Rebs. Like Cowboys and Indians, only Yankees and Rebs. He attended Stone Elementary School and visited his grandmother, and once in a while he went with his dad to a place called the Cotton Bottom Lounge.

The Cotton Bottom parking lot was where his mother once fired a gun in anger, and the Cotton Bottom jukebox was where white men would sometimes forgo the Faron Young stuff and play Lightnin’ Hopkins’ “Short Haired Woman”. They’d play it for a laugh, chortling at the part about buying rats all the time. Taylor was in there with his father one time and heard this going on. That was the blues, for the first time, and it was a big deal to a nine-year-old kid who had no damn business being in the Cotton Bottom Lounge.

“I thought it was great,” he said. “Great.”

Taylor wrote about his father later on. Killed him off in “Charlie Ray McWhite”, referenced him in “Walkin’ Back Home”, and offered a clear, pained recollection in “Depot Light”, a song set in Greenville’s since-demolished Southern Railway depot. That song’s full of lines. “He gives his coat to the one-armed man/Empty sleeves and safety pins/And the all-night waitress just talks too much/So he steals her spoon and her coffee cup.” Denice Franke says Eric Taylor is always true to the line. “We’ll be home by nine if we take the tracks/And if she’d come home, boy, I’d take her back.”