25 YEARS OF NO DEPRESSION: Joe Henry on ‘Helping People Feel Fearless’

EDITOR’S NOTE: To mark No Depression’s 25th anniversary, we asked David Menconi, a contributing editor during its earliest years (1995-2008), to check back in with artists who appeared in the magazine’s first few issues. Read the rest of the stories in this series here.

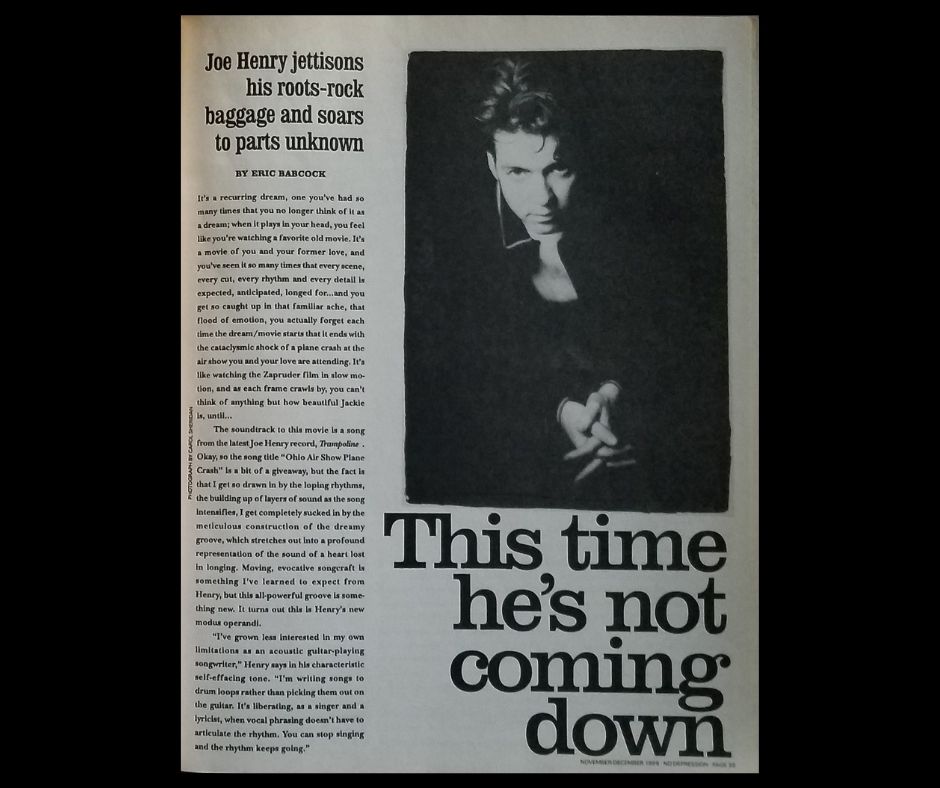

The first No Depression feature on Joe Henry came in issue No. 6, November-December 1996, a piece written by Eric Babcock, and it came at a major period of transition for him. Following a series of excellent yet fairly conventional country-rock albums (including two made with the Jayhawks forming the core of his backup band), Henry was feeling stifled. So he took a hard-left turn on 1996’s Trampoline, which was a series of songs that were more about atmospheric grooves than conventional song structures.

The fact that he made this move away from Americana just as it was gaining critical mass as a mainstream format was not lost on either Henry or his handlers. “Various people in my camp have suggested that it was foolish of me to jump off the bandwagon just as it gained corporate sponsorship,” is how he put it in that 1996 interview.

“I heard that from a number of people for a long time, as it became identified as a genre with legit stars,” Henry says now. “You know, ‘Why would you slip out of the uniform just as you were being commissioned?’ But I never thought that would be my permanent musical vocabulary. As time went on, as a record-maker I felt like I was doing live theater when what I wanted to be was a filmmaker, with more range and the leeway to create atmosphere around songs.”

Even bigger changes were in the works for Henry, and that boundary-pushing also came to define his then-budding career as an acclaimed record producer. He has become first-call producer for artists looking to make a certain kind of record — one more focused on capturing a moment than a sound ground down to perfection — since winning the first of his three Grammys for Solomon Burke’s 2002 comeback album Don’t Give Up on Me.

“I don’t twiddle knobs,” Henry says of his production methodology. “For me, being a producer is about helping people feel fearless. It’s not about arrangements so much as inviting the right people into the room. At this point in my working life, I’m less interested in what people play than who they are. I don’t want Jay Bellerose just as a drummer, I want his spirit and point of view in the room. Every musician I work with, it’s like that — they’re there first and foremost because of life experiences and humanity. The instruments come later.”

Being a producer got Henry onto No Depression’s cover (issue #61, January-February 2006) a decade after his first appearance in the magazine. By now, Henry’s production résumé includes Bonnie Raitt, Joan Baez, Rhiannon Giddens and Carolina Chocolate Drops, Ani DiFranco, Steep Canyon Rangers, and a whole galaxy of classic soul stars — Bettye LaVette, Mavis Staples, Irma Thomas, and Allen Toussaint among them. He has also continued making his own records, releasing 16 albums to date.

Henry’s most recent album came out in late 2019, The Gospel According to Water, which might be his finest work to date. Henry wrote this set of songs while undergoing treatment for cancer (happily, the 59-year-old Henry is in remission), although he says the album is not about that. Then he spent several days in the studio recording what he thought were demos only to discover that he’d unwittingly recorded the album. He released the recordings as-is, and even though it’s spare and stripped-down, Henry believes the Gospel album is “as ‘produced’ as anything I’ve touched.”

Henry specializes in an of-the-moment production aesthetic, which he usually applies to other artists. In many ways, however, The Gospel According to Water feels like the ultimate example of that.

“There’s an attitude that something that happens live or quick is by nature ‘less produced’ and ‘just happened,’” he says. “But it’s every bit as much of a production decision to limit time in the studio with a small group as it is to do orchestrations and arranging. Both require vision about how they’ll emotionally register. There’s that Leonard Bernstein quote, ‘To achieve great things, two things are needed: a plan, and not quite enough time.’

“With Gospel, I made a decision: How raw can this be and still feel complete?,” he adds. “And that’s how it happened, as a moment of raw expression. I’m a big believer in on the spot, now is the time. You can peck away at something, come back three weeks later with a different bass player, try to pick it back up. That’s just fishing around and it doesn’t work for me. I like something that sounds like human beings leaping out of the speakers. Some records that were just made already sound like artifacts, but Robert Johnson still sounds alive.”

David Menconi is a music journalist in Raleigh, NC, who has written for publications including Billboard, Spin, Rolling Stone, the Raleigh News & Observer, and No Depression — where he was a contributing editor for the magazine’s original 1995-2008 incarnation. His next book, Step It Up and Go: The Story of North Carolina Popular Music, from Blind Boy Fuller and Doc Watson to Nina Simone and Superchunk, will be published in October by University of North Carolina Press.