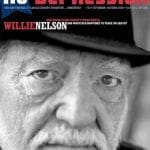

Willie Nelson – Gonna catch tomorrow now

Luck, Texas, isn’t as easy to find as it used to be. Development has sprawled the entire 25 miles from downtown Austin to this idyllic little spot in the Hill Country near Lake Travis where Willie Nelson created his own universe more than two decades ago. The old corner store that was once a landmark is now a bank. The entrance gate is practically lost among the McMansions and ranchettes that have sprouted up.

This fact of life is not lost on the guy in the Willie Nelson T-shirt driving the mower over the fairway of the Briarcliff Country Club. After providing directions to a wayward tourist, he wisecracks, “Welcome to Oak Hill,” referring to the suburb fifteen miles closer to the city.

Still, there’s enough acreage surrounding Luck that once you stumble onto the dirt main street, you realize Willie Nelson’s home base is safely in a zone of its own. The cowboy town of faux buildings — including a feed store, barn, gunsmith, church, and bathhouse — hasn’t changed much since it was built for the film Red Headed Stranger in the early 1980s. Unchanged, but deteriorated to the point that Luck today looks less like an Old West movie set and more like a real 20th-century small town in Texas that is drying up and blowing away. Whatever it is, it is Willie’s World. The rest of us are just visiting.

I had come for my last sit-down with Willie Hugh Nelson. I’d been writing about him since I hit Austin in 1973, a year after he did. I’ve spent the ensuing years listening, watching, and observing him as he played shows on flatbed trucks, in drive-in movie theaters (with Paul Simon sitting in, no less), in amphitheaters, in performing arts halls, and at too many July Fourth Picnics to count. Somewhere along the way, the television appearances, movie roles, and inductions to various halls of fame added up to Willie achieving some kind of sainthood, with just enough speed-crazed hustlers, soulful used-car salesmen, and honest-to-Sam-Houston characters to keep me engaged.

Like Austin, Willie too has changed along the way. He came to the game as a songwriter. Some say that particular skill fell by the wayside decades ago — that he’s sliding by on cruise control, that he hasn’t written a memorable song in years. And yet, in the midst of all his albums of cover songs, tribute songs, collaborative affairs with high-profile buddies, television specials, and films, he’s still continued to write songs — including an antiwar protest number that briefly stirred up a hornet’s nest of controversy late last year. Not to mention enough straight-ahead country tunes to justify a full-blown album that may be his best work in ages (It Will Always Be, due October 26 on Lost Highway).

But even if he hadn’t written a line in a quarter-century and decided to follow the path of Fats Domino — who once reasoned he didn’t need to write another song because he already had more than enough hits to perform in concert — Willie would justify a visit, just because he’s Willie. After all, he personifies the outlaw movement that presaged alt-country. He’s the one credited for putting Austin and Texas Music on the map. He’s a pop culture icon, bandanas, pigtails, running shoes and all, the one Texan more popular than George Bush. He’s the gold standard for Texas marijuana: If it’s Willie weed, i.e. pot fit for him, it’s top-of-the-line bud. And he’s just mysterious and mystical enough to keep everyone guessing. You never know what you’ll find when you’re in Luck.

That said, we’re both old enough to be lucky just to be alive.

He’s 71. I’m 53. We’ve both done a pretty fair job taking care of ourselves. While Waylon kept roaring until a few years before his death in 2002 at age 64, Willie quit the powder and the partying back when he was about my age. These days, drinking means water more often than whiskey. His biggest vice remains his appreciation of the sweet smoke.

Change at this stage of the game usually means some kind of diminishment, and in the case of Willie, the black cast on his left forearm was a big red flag. Carpal tunnel syndrome, the repetitive motion injury of the computer age, had finally gotten to him. He had scrunched and contorted his fretting hand into chords on his battered guitar, Trigger, one time too many. The surgery that was required to fix the problem knocked him off the road for the first time since…well, forever.

But it wasn’t just him who was hurting and hobbled.

His friend Ray Charles had passed away five days before. Willie’s drummer and lifelong partner in crime and other adventures, Paul English (of “Me And Paul” fame), can’t make it through an entire show anymore. Paul’s son, Billy English, carries the load when it comes to keeping the beat. Another drummer during Willie’s outlaw glory days, Rex Ludwick, passed on earlier in the year, his life cut short from too much drinking. Even the title of Nelson’s new CD, It Will Always Be, especially the track “Tired”, suggests loss and resignation.

So Mr. On the Road Again had been forced to adjust to the sedentary life off the road. Not that his band minded — 220 dates the previous year were a few too many for some of his players, all of whom except Paul are younger than Willie.

I thought I’d done my last interview with him five years ago, when he drove me around Luck in his pickup truck and I caught him off-guard when I asked whether there were times when he got tired of being Willie. His response — “Not really, but if I do, I go and hide” — said a lot. He’s very much a public figure who enjoys his station in life. Wouldn’t you enjoy it if everyone around you acts glad to see you and showers you with compliments? But he’s also human enough to enjoy his privacy and the opportunity to chill whenever he can.

Two years ago, I went to the well one more time, speaking to him by phone while he was on his way to play a show in Nebraska for a club owner friend who was down on his luck. That really, really, really was my very last Willie story, I thought. What else was there for me to ask? What else was there for him to say?

That’s what I got for thinking.

Between releasing It Will Always Be, performing relentlessly, recording prolifically, appearing in commercials and TV specials, plotting more film roles, speaking out on behalf of family farmers, Dennis Kucinich and marijuana, and writing one of the first protest songs against the war in Iraq, Willie is living ten lives at once. The most stunning example is the new album, a full-blown, state-of-the-art polished piece of work that rings with clarity and purpose like his recordings of thirty years ago.

Not bad for an old fart who’s supposed to be in his autumn years.