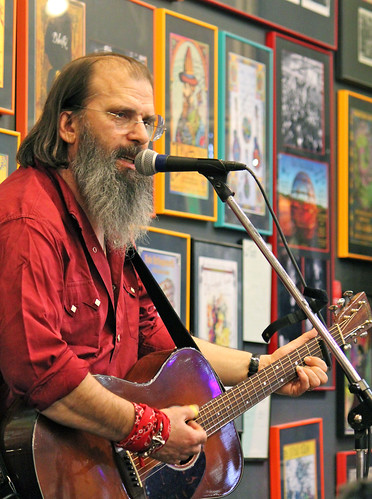

Traveling Along the Low Highway, Steve Earle Sees Woody Guthrie’s America

Steve Earle was celebrating in Denver on Saturday night, and it had nothing to do with the Mile-High puff daddies hanging out near Colfax Avenue just two miles to the west.

No, the alt-country outlaw was enjoying his role in Record Store Day on the 25th anniversary of Twist & Shout, one of the city’s final vinyl landmarks.

Making an in-store acoustic appearance, Earle was friendly, animated and talkative during extended breaks throughout a six-song set that included five from his April 16 release The Low Highway, his 15th studio album.

Cheetos and Twinkies were nowhere in sight. Earle’s lone refreshment was an occasional sip of bottled water. But on the unofficial national holiday known as 4/20, when thousands gathered in Civic Center Park for what was billed as the largest pot smokeout in the country, Earle, a recovering drug addict and alcoholic since the mid-1990s, did poke fun at some of the celebrants. Like most in the record store, he apparently was unaware that a few gunshots had disrupted the event extolling the wonders of marijuana in the aftermath of Colorado’s recent legalization of the drug.

A series of loud beeps in the store following his song “Invisible” (the video was directed by Tim Blake Nelson) got Earle’s attention.

“Whoa! Somebody over from the pot thing is beeping,” he said. “I saw those guys leaving there today, man, and everybody was eating something. Funnel cakes bigger than their heads, hot dogs …”

Earle, who has been on the road practically full-time since his previous record, I’ll Never Get Out Of This World Alive, was released in 2011, maintained a lighthearted mood for most of the 30-minute set as a Hardcore Troubadour group of fans lodged in between record bins to get a fairly close look. Many of them pre-purchased Earle’s latest, available in three formats (CD, CD/DVD combo, LP), to gain a guaranteed spot in the autograph line afterward and to get entered in a drawing for an Earle-autographed guitar.

“I’m honored to be here on this day,” said Earle, who had made three previous Twist & Shout appearances and was wrapping up a series of four promotional in-store dates throughout the West. “I fought for it and I’m glad we got to do it. You really need to support this place; it’s really important and it becomes more important every day.”

Returning to New York for a Monday night appearance on Letterman and three days of rehearsals before resuming his road work, Earle mentioned he would return to Colorado this summer (including dates with the Dukes at the Boulder Theater and the Ride Festival in Telluride).

Also on the summer agenda, Billboard announced Tuesday, is the June 25 release of Steve Earle: The Warner Bros. Years, a box set to include three albums he recorded from 1995-97, along with the previously unreleased Live at the Polk Theater concert album and To Hell and Back, a DVD of a 1996 show from the Cold Creek Correctional Facility in western Tennessee.

Now shaping up for yet another tour, he teasingly took a swipe at the southwest Colorado mountain town with an elevation of 8,750 feet that’s the home of the renowned Telluride Bluegrass Festival, where he has performed multiple times.

While humorous remarks such as those were frequent, Earle had his serious moments, too, explaining his journey on The Low Highway after opening with the title track.

“I was out on the road, had the best band I’ve ever had out on the road supporting the last record and I decided first I wanted to make a record with the band,” Earle said of the Dukes (& Duchesses that include his gifted singer-songwriter-wife Allison Moorer). “And that’s what we did. …

“I was writing songs for (HBO’s dramatic series) Treme already (Earle played down-and-out musician Harley Watt, who was shockingly killed off near the end of Season 2), and the story of Treme is the story of post-Katrina New Orleans. And the story of post-Katrina New Orleans is linked directly to these economic times that we’re dealing with. Because the reason things haven’t recovered as fast as they should in New Orleans — still to this day there’s half the people there were before — the reason that things haven’t bounced back the way they should is ’cause of money. … You can’t take over the world and lower taxes at the same time. It just doesn’t work. It never has.”

After a smattering of applause, Earle continued.

“So I kept looking out the window of the bus and writing the songs. And what I saw, I suddenly realized, was something close to what Woody Guthrie saw. This job that I do was invented by Bob Dylan as he was sort of creating himself more or less in Woody’s image. And all of us that have done it in his footsteps have done it with one foot in the 1930s, one foot in the Depression. Music that stylistically is linked to the Depression.

“Even kids that are doing it now; there’s a fashion to the Depression. They’re trying to look like The Band and The Band were trying to look like the Depression. So it’s one of those deals. The epiphany was that none of us that have done this job, including Bob, ever witnessed that firsthand. Until now.”

Earle also shared his disenchantment with Walmart in “Burnin’ It Down,” paid tribute to the late founder of San Francisco’s Hardly Strictly Bluegrass in “Warren Hellman’s Banjo” (“Just because you’re rich, you don’t have to be an asshole,” he surmised) and capped it with a rousing rendition of “Copperhead Road.”

As a storyteller and songwriter, though, Earle soundly connected with the moving account of John Henry, his and Moorer’s 3-year-old son who was diagnosed with autism a month before his second birthday.

Regarding John Henry’s development, Earle ended on a hopeful, mostly positive note. “He’s socially engaged in ways that are really encouraging for the people that are teaching him and for us,” Earle said. “He quit talking, and he’s still not talking. But he’s in school and we have resources. And he’s smart and he looks like his mother, and he’s gonna be fine.”

Stating that autism is an epidemic “bigger than AIDS” and despite “all the other stuff that they scare you with, this we gotta solve,” Earle then grabbed hold of the audience with an affecting, affectionate touch on “Remember Me,” which closes the 12-song album:

I can only hope I do my best /

With whatever time that we got left /

And when everything’s done and said /

You’ll remember me

It was a moment that, like Earle himself, will be impossible to forget.

Steve Earle photos by Michael Bialas. See more from the Twist & Shout appearance and the 2011 Telluride Bluegrass Festival.