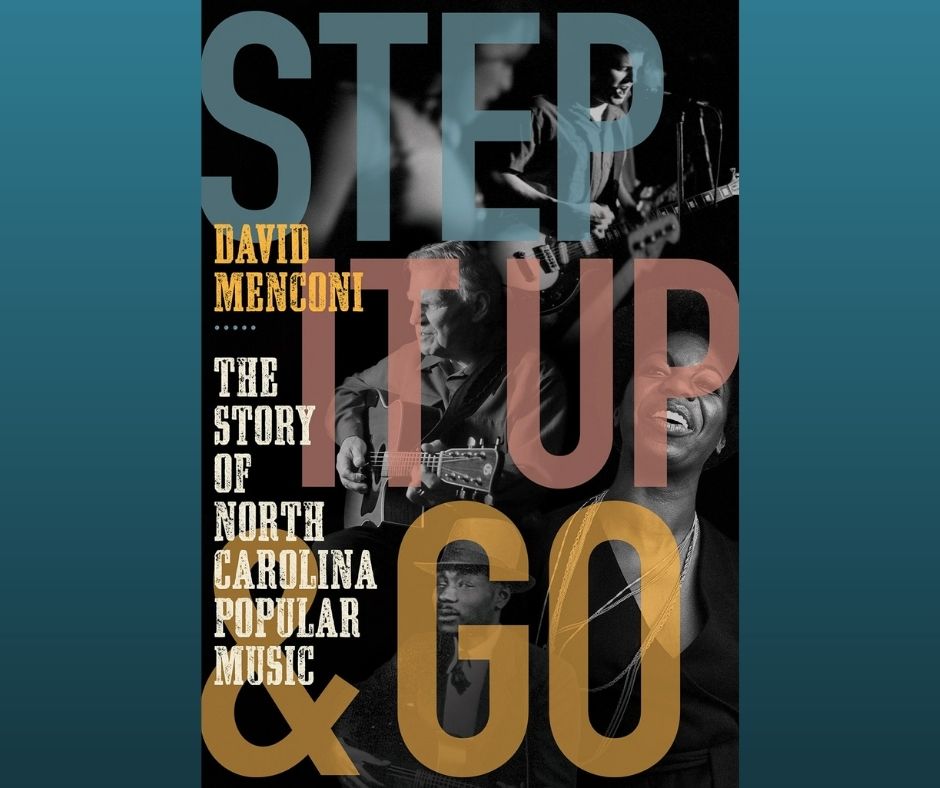

THE READING ROOM: Music’s Starring Role in North Carolina

David Menconi’s Step It Up and Go: The Story of North Carolina Popular Music, From Blind Boy Fuller and Doc Watson to Nina Simone and Superchunk (UNC) tells tales as colorful as the mountain laurel blossoms in the state’s mountains and as expansive as the warm sands on the state’s beaches. With a troubadour’s heart, he tramps across the richly loamed Piedmont and the fragrant fields of tobacco in the eastern counties talking to musicians, listening to stories, sitting a spell on porches or in kitchens enthralled by the voices of artists or the plunk of banjos and scrape of fiddles in search of the musical roots and branches of North Carolina music.

Menconi, music journalist and former staff writer at the News & Observer in Raleigh, reveals in the many stories he’s collected here, and in the rich historical portrait he paints, that “music is North Carolina’s tuning fork … because it’s not just in the air here, but also the soul.” He goes on to write that “modesty becomes us here in North Carolina, and that outlook extends to our music. Indeed, music itself is the star here, as embodied by modestly inclined musicians like Alice Gerrard and Etta Baker. Even for non-natives (and Gerrard was born in Seattle), the music of North Carolina is a homing beacon they didn’t even realize was there until they had the same experience I did: coming here and immediately connecting with it as home.”

Over the 16 chapters of Step It Up and Go, Menconi chronicles the history of North Carolina music by telling the stories of the people who made the music. From the opening chapter, “Linthead Pop: Charlie Poole, the Father of Mill-Town Rock (and the First Rock Star),” and through chapters with titles such as “Rocket Man” (about Earl Scruggs and the birth of bluegrass), “Y’alternative” (about the rise of Americana), and “Famous on Television” (on North Carolina’s strong showing on American Idol) Menconi charts the state’s musical DNA from bluegrass to gospel, from jazz to rock, from blues to hip-hop.

The book opens on Charlie Poole, a linthead — slang for Southern white millworkers — who grew up following his family into the textile mills near Greensboro, but who discovered the banjo, wrote some songs, got together with fiddler Posey Rorer and guitarist Norman Woodlieff to form the North Carolina Ramblers, and eventually rambled off to New York City to record his best-known song, “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down Blues,” among others. Over the course of his career Poole cut more than 80 songs, and by 1927, Menconi writers, “Columbia Records’ catalog included a picture and caption calling Poole ‘unquestionably the best known banjo picker and singer in the Carolinas.’” Yet Poole seems hardly to be remembered in “official” country music history, and by the time of the writing of his book Menconi reports that Poole had still not been inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. In spite of this snub, his name and music is being carried on by artists from the Carolina Chocolate Drops to John Mellencamp and Loudon Wainwright III, who won a Grammy in 2010 for his tribute album to Poole titled High Wide & Handsome: The Charlie Poole Project.

One of North Carolina’s most famous musical exports is beach music. The music bears no resemblance — other, perhaps, than having a beach and the ocean as its backdrop — to the California sound of Jan and Dean or The Beach Boys, or to the New York surf sound of The Fantastic Baggys. Beach music provides the soundtrack to shagging, the official dance of Topsail Beach, North Carolina, and Ocean Drive, South Carolina. “The official state dance of the Carolinas … shagging takes many forms,” Menconi writes. “It involves a wide range of moves, most of them based on a six-count step. … It’s a relaxing style of music and dance, steeped in the temporal romance of vacations, parties, and summer love.”

The chapter on beach music focuses on The Embers, the quintessential beach music band that has been playing songs for shagging to for over six decades. Their version of The Tymes’ “Miss Grace” continues to fuel many a summer romance under the pier, or to bring back memories of long-ago nights of romance at the beach. The Embers’ most famous song, “I Love Beach Music,” has ended the band’s sets since “original front man Jackie Gore wrote it in 1979.” As Menconi points out, “Beach is a subset of soul where The Clovers are as important as James Brown. And The Embers, a band that has never had a national hit on the mainstream pop charts, is among the biggest in the field.”

Each chapter contains numerous black-and-white photos that bring to life the artists about whom Menconi is writing. In addition, every chapter features sidebars that provide more detail about some of the artists and genres covered in the chapter. For example, the sidebar on Billy Strayhorn highlights his move from Pittsburgh to Hillsborough, North Carolina, the town that David Hadju called Strayhorn’s “spiritual home.” Strayhorn, of course, went on to become Duke Ellington’s long-term collaborator and co-writer of such standards as “Take the ‘A’ Train.”

As Menconi points out, the thread that ties these stories of North Carolina music together is “a similar sense of determined, workmanlike focus, as well as ensuing, ingenious artistry. It’s not universal, but most of the great North Carolina artists I’ve encountered don’t take themselves nearly as seriously as the rest of the world does. Some of the state’s most notable musicians have been non-professionals who held down day jobs and still kept that mindset after turning professional.”

Step It Up and Go captures the rich diversity of North Carolina’s music through colorful stories, poignant photos, and humorous anecdotes. Menconi’s a masterful storyteller and a delightful guide to the music of the Tar Heel state, and every chapter in the book deserves to be lingered over and treasured for its loving attention to the details of the lives and music dwelling in the state.

Here’s a Step It Up and Go playlist curated by Menconi to show off some of the songs of the Tar Heel State: