THE READING ROOM: Books to Help Understand (and Dismantle) the Culture of Racism

As the time comes to write another column about books, I struggle. It’s not because of my recent health issues, or any dearth of music books about which to write. My struggles arise from speaking to the travails of our culture, as exemplified most recently in the unjust and unjustified killing of George Floyd by the police in Minneapolis and the hateful killing of Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia while he was jogging in his own neighborhood. The inequities in America are fostered by racial divisions and the persistent racial segregation characterized by poverty that creates destitute individuals and communities, and those divisions deepen every day, driven by an amoral political leader more concerned about his ego than any one of the American people.

I grew up in the South, born in Gastonia, North Carolina — a town that is no stranger to racial unrest and labor disputes — and grew up in South Carolina and Georgia. My family has roots in a small South Carolina town, and my father’s father was the chief of police in that small town. Growing up, I heard plenty of stories about how my grandfather had handled cases involving black men — I didn’t have the phrase “police brutality” when I was a child, but my grandfather’s actions would today certainly be described in such terms — and my father and uncle peppered their talk with derogatory terms for black men. Even as a fifth grader, I loathed such language, though I regret to admit that I was mostly silent and didn’t challenge my authoritarian father. When we lived in Charleston, South Carolina, I witnessed white people beating blacks and remember crying and being very scared for the people being beaten. I didn’t know how to respond, and my parents offered little support since as far as they were concerned such actions as beating and “keeping blacks in their place” were part of the fabric of society as they knew it.

By the time we moved to Atlanta, I had started to read more about the civil rights movement, and one of the books that changed my life was a little anthology called Black Protest: History, Documents, and Analyses: 1619 to the Present (Fawcett), edited by Joanne Grant. I read Stokely Carmichael, Eldridge Cleaver, and Martin Luther King Jr., and I questioned my parents about their attitudes toward blacks. Why did we have to treat them a certain way? Why did we call them names? Why, when many of them met hate with love, couldn’t we — who went to church every Sunday and claimed to be Christians — love black people and not hate them? I remember crying when Martin Luther King Jr. was killed, and my father simply sat and sneered and asked why I would cry for somebody like King.

I realize now that my parents’ attitudes grew out of fear of the unknown. They had grown up a certain way and were taught to fear anything or anybody that wasn’t like them and their culture. Still, that fear fostered hatred, and by then I had found my voice, and a community with whom I could share my views and with whom I felt a bit of solidarity. When I went to a small college in West Palm Beach, Florida, I was one of the “radicals,” becoming involved in protests against the Vietnam War, in support of civil rights, and even against the building of Disney World. I was hopeful back then that the world was changing for the better — this was 1972 — and that the future might indeed one in which individuals embraced one another for who they were, helped each other out of love and out of the ground of our common humanity, and believed in a common good.

Over the past few days, I have been listening over and over to Kyshona’s most recent album, Listen. Even though the album came out earlier this year, her lyrics couldn’t have been more prescient. On the title track, she issues a simple plea, “Why don’t you listen?” In the song’s final verse, she declares, “I’m standing right in front of you / Trying to tell you my truth / The only thing I ask of you / Is listen / Why don’t you listen?” Clearly, we live in a world that prefers noise and occupying space with words rather than a world of quiet where we are attentive to the sounds around us and to the pleas and cries and questions of others. We judge others even when they’re standing next to us and we can see their pain and hear their questions, but we too often fail to listen deeply so we can understand and know others.

At least for the past week or so, I have been listening to music more than reading about it. I have been reading, or re-reading, books that address in one way or another the divide in which we find ourselves. I wish I could be more hopeful about the state of our society, but I can at least take action and participate in changing the ways we see the world. Here’s a very short reading list that can help all of us enter the conversation and listen:

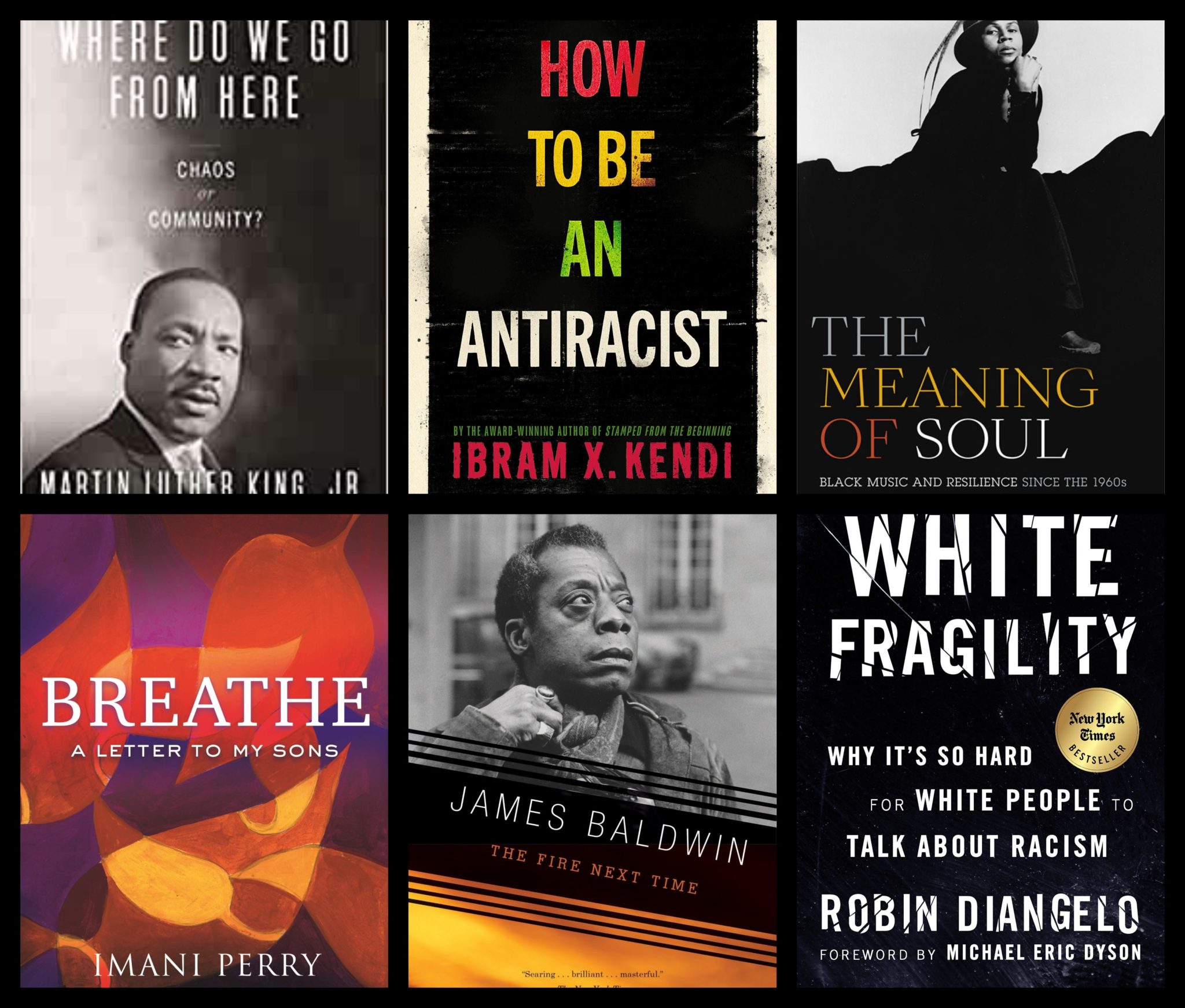

Emily J. Lordi, The Meaning of Soul: Black Music and Resilience since the 1960s (Duke; coming in August 2020)

Aaron Cohen, Move on Up: Chicago Soul Music and Black Cultural Power (Chicago)

Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (Bold Type Books)

Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (OneWorld)

Martin Luther King Jr., Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (Beacon Press)

James H. Cone, A Black Theology of Liberation (J.B. Lippincott)

John Howard Griffin, Black Like Me (Signet)

Bryan Stevenson, Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption (OneWorld)

Mikki Kendall, Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women That a Movement Forgot (Viking)

Robin DiAngelo, White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism (Beacon)

Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (Harcourt)

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Crossing Press)

Angela Y. Davis, Women, Race, & Class (Vintage)Bottom of Form

Eddie S. Glaude, Democracy in Black: How Race Still Enslaves the American Soul (Broadway Books)

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (Vintage)

Malcolm X, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (Ballantine)

Jesmyn Ward, The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks about Race (Scribner)

Reni Eddo-Lodge, Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race (Bloomsbury)

Jonathan M. Metzl, Dying of Whiteness: How Politics of Racial Resentment is Killing America’s Heartland (Basic Books)

Imani Perry, Breathe: A Letter to My Sons (Beacon Press)

Emily Bernard, Black is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother’s Time, My Mother’s Time, and Mine (Vintage)

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration and the Age of Colorblindness (New Press)

Saeed Jones, How We Fight for Our Lives: A Memoir (Simon & Schuster)Bottom of Form

Howard Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited (Beacon)

Katie Geneva Cannon, Katie’s Canon: Womanism and the Soul of the Black Community (Continuum)