THE READING ROOM: A Guide to the Music and Musicians in the Cajun Tradition

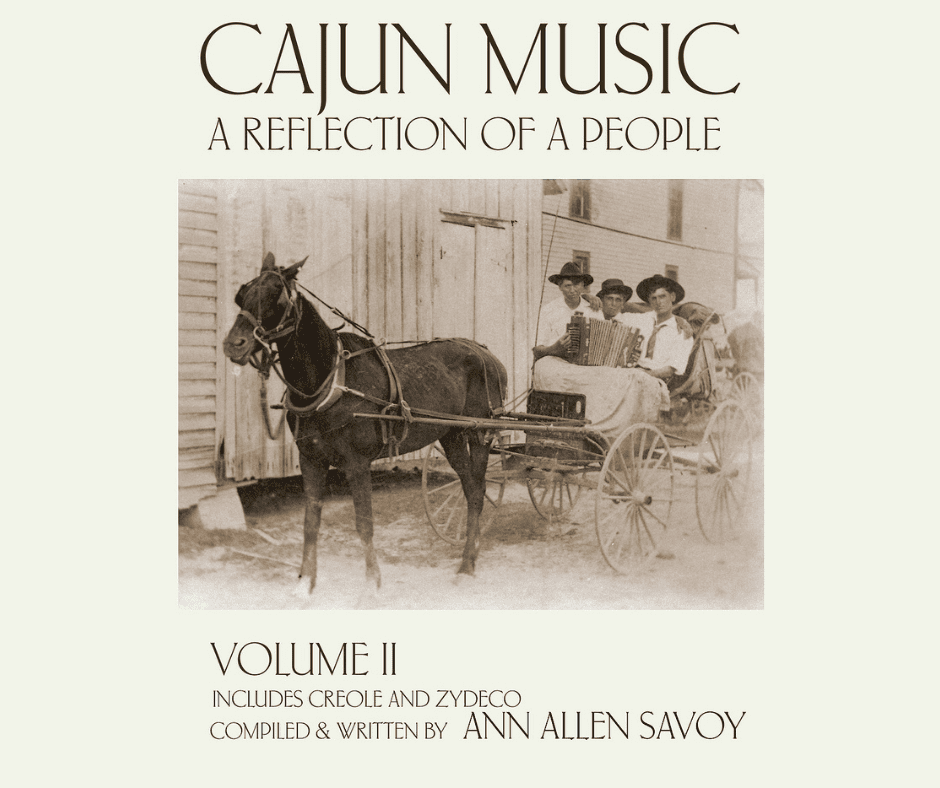

Cajun Music: A Reflection of a People, Volume II (Bluebird Press) has been a long time coming, and it’s well worth the wait. Continuing along the lines of the first volume, published in 1984, Ann Allen Savoy’s breathtaking sketches of the music and musicians provide a sweeping panorama of the history of Cajun, Creole, and zydeco music.

Like the first volume, the newly published second volume is lavishly illustrated with hundreds of black-and-white photographs and includes more than 35 interviews in English, Cajun, and French and biographies that illumine the lives and musical careers of artists such as Boozoo Chavis, Happy Fats, Harry Choates, Nathan Abshire, Octa Clark, Chester “Pee Wee” Broussard, and Wilfred Latour. Cajun Music: A Reflection of a People, Volume II also includes more than 100 songs with French translations and phonetics, as well as informative mini-histories of the role of certain instruments, such as the steel guitar, early rhythm instruments, and drums, and a sketch of dances in Louisiana.

Savoy herself has played an integral role in preserving and transmitting the music to new generations through her own playing and producing. She and her husband, accordionist Marc Savoy, and their children formed The Savoy Family Band and collaborated with Beausoleil’s Michael Doucet in the Savoy-Doucet Cajun Band. Savoy formed The Magnolia Sisters, an all-female Cajun band that joined forces with Linda Ronstadt as the Zozo Sisters, whose album Adieu False Heart was Grammy-nominated, one of four such nominations she’s received to date. Savoy has also performed and recorded with her gypsy jazz ensemble Ann Savoy and Her Sleepless Nights. She produced Evangeline Made: A Tribute to Cajun Music, which featured performances of classic Cajun repertoire by Ronstadt, Linda Thompson, and John Fogerty, among others, as well as Creole Bred: A Tribute to Creole & Zydeco which included tracks by Cyndi Lauper and Taj Mahal.

Marc Savoy provides a brilliant little “personal history of the accordion in Louisiana” in which he chronicles not only the history of the accordion and its role in Cajun music but also his building his own music store — Savoy Music Center — and his own accordions. When people asked him why he was opening up a music store in the middle of a cotton field far away from any city, what they really meant, he writes, is “it was unheard of for someone to open up a business that specialized in in Cajun music.” Upon reflection, Savoy thinks “my ulterior motive was to prove to Cajuns and non-Cajuns alike that heritage and success could co-exist. You could conduct business in the French language just as well as in English. You don’t have to give up the things that make you who and what you are to be successful in this world. It was ok to be different from the mainstream.”

Every one of Ann Savoy’s biographical sketches or interviews is a little gem that highlights the life and music of its subject. In her biography of the Cajun accordionist and fiddler Austin Pitre (1918-1981), for example, she narrates his story and shows the ways that his life lent a rawness to his music. Born into a family of sharecroppers in Ville Platte, Louisiana, the northern edge of Cajun country, Pitre knew the music of the worlds of “the old time house parties where he played throughout the Mamou area as a child with his father, and later the Cajun dancehall circuit of the 1940s-1970s.” Following World War II, Pitre started up his band The Evangeline Playboys, who became well known along the dancehall circuit, playing eight dances a week at various halls. As Savoy points out, Pitre left behind a body of music that was an “example of the powerful, raw dancehall sound that is fast disappearing from the prairies — the sound of hard work, sorrow, and killing good times.”

In the pages following her biographical sketch of Pitre, Savoy and Daniel Coolik provide transcriptions of several of the songs with which he’s associated, including “Pretty Rosie Cheeks” and “The Evangeline Playboy’s Special.”

In an interview with Wilfred Latour conducted in 1986, Savoy allows the great accordionist to offer his version of the differences and similarities between Cajun music and zydeco and to explain his own style of music: “I play a variety of music. I can play the real Cajun French, I mean two-step, one-step, waltz and things like that. Then I play zydeco — that’s that different style, a different rhythm of music. Zydeco is mostly a combination of blues and French. In other words, you can take a blues, I’m talking about the slow rhythm of music, and you can take a two-step, and you can play it at a certain tempo. Well, you come up with an accompanying different rhythm. So really that’s how zydeco started. … It’s a combination of that French music, with the blues and the rock music.” Coolik and Savoy include transcriptions of songs associated with Latour, including “I’m Gone” and “You Play Sick When I’m at Home.”

Cajun Music: A Reflection of a People, Volume II is a treasure trove of music history, providing a wealth of insights into the development of a musical tradition and preserving the stories of the many artists who created this music that continues to flow colorfully into our world. We are fortunate that Savoy has devoted so much time and energy to this work and has presented us with a gift of such enduring value.