Spirituals against Frolics : early evangelization in the British colonies until 1800

In a cultural evolutionist perspective there is a long line connecting the blues music to the first slaves who arrived on the soil of the north American continent at the end of the 1610’s in Virigina and on the Sea Islands before the coast of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. In this approach, the African heart of the blues started beating at that time. In a contextual approach, it is observed that already then the acculturation of Blacks in the New World germinated, and that European blood started to enter the cultural veins of what would later become a new American music.

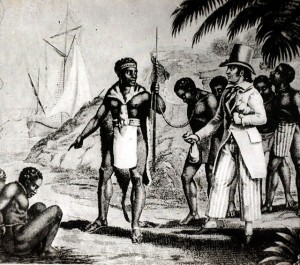

On the ships that brought them from West Africa or indirectly from the Caribbean, the slaves had been confronted with the European music which was ‘weird’ compared to their African culture. During the long journey, the slaves were brought onto the deck to exercise in the name of their physical and mental health. This exercise, violently forced, often consisted of dancing to European music provided to them by members of the boat’s crew. The slaves danced to the hornpipe or fiddle, unfamiliar instruments played in a for them unfamiliar march-time beat by members of the ships’ Europeans crews (Richard W. Bulliet et al, 2010). The crew itself also exposed the slaves to their sailor songs when they prepared the ship for departure or when they exercised to keep their body in good condition during a journey which lasted between 2 and 6 months. Some ships disposed even of small bands and orchestras. Sailors whiled away the long weeks on the journey by drinking, dancing and singing (Barry Clifford et al., 2008). The “College Hornpipe” (later known as the Sailor’s Hornpipe) – a tune first printed around 1797 – imitates the life of a sailor and his duties aboard ship. Sailors from the Royal Navy are supposed to have invented this solo dance as an exercise aboard ship in line with an existing tradition of dancing to keep the lower body in good shape. The accompaniment may have been the music of a tin whistle or, from the 19th century, a squeezebox.

Once arrived ashore – if still alive – and after being “prepared” for the market the Africans finally reached what would become their new “home” and where music from both Africa and Europe “greeted” them. Slaves were also put to work on the musical field. Some plantation masters developed a habit of kidnapping slaves from other plantations who were rumored to be good musicians. The masters would then have the slaves trained to play fiddle, or other European instruments for their own entertainment. These slave ensembles played at formal dances at the master’s house and at country dances for the white people (Marcus). It seems plausible that there was feedback from these “privileged” house slaves to the other less fortunate field slaves.

The cross-fertilisation of cultures had started. In this process, Epstein (2003) underlines, it is hard to overstate the importance of the conversion to Christianity, which was an essential precondition for the emergence of the Negro spiritual. Together with work songs, shouts and hollers, spirituals would provide for a fertile soil in the cultivation and growth of the later blues music. In what follows, I will sketch the first traces of conversion to Christianity in the British colonies up till the end of the 18th century. This shows that there are further arguments for the supposition that already in a very early stage some European elements sneaked their way into the African culture of the newly arrived slaves. At the same time, it highlights that the conditions for the gradual acculturation where defined by the Caucasian proprietor.

For a better comprehension, one needs to keep in mind that the process of ‘winning souls’ was different in the northern British colonies compared to the southern French and Spanish colonies. The juxtaposition of the historical background of slavery and the social-economic and cultural differences between the British colonies on the one hand and the Roman-Catholic Spanish and French colonies on the other hand are an important factor which can help to understand later divergences in musical evolution. As far as Christianization is concerned, the planters of the South started already from their arrival to bring the slaves up “in the knowledge and practice of the Catholic religion”. As a contemporary historian of South Carolina and Georgia, Alexander Hewatt (1739–1824) reported, “Masters and slaves under the French and Spanish jurisdictions are obliged by law to allow them time for [religious] instruction”. Roman-Catholics also had a different, more flexible view on what was allowed or not during the Sabbatical day, but that is matter for another article.

As for the evangelisation in the British colonies, roughly speaking three major periods can be distinguished between the arrivals of the first slaves in Virginia in the first decades of the 17th century until the end of the 18th century.

1619-1700

In the first period which runs until the end of the 17th century there is no interest from the white planters for the religious, and in general for the cultural background of the Africans. The latter were considered as heathens, pagans, and little distinction was made as to their possible heterogeneous religious belief systems. If an African ‘soul’ was saved, it was on a purely individual basis mainly within the direct relation between the master and the house slave.

Let us note in this context that it was only as from 1660’s onwards that with the spread of the tobacco plantations the demand for labour started to outgrow the available labour supply coming not only from Africans but also from indentured whites who came from the British isles and who had to labour to pay back their cost of transportation . Only then, the Virginia colony revised its legal dispositions to rule that blacks could be kept in slavery permanently, generation after generation. An influx of slaves was boosted at that same time by a drop in the value of sugar grown on Caribbean islands which incited the planters there to sell their “property” to the tobacco farmers in Virginia. Moreover, it were not only blacks who were sold in slavery. There are documents that show us that also Scots were sold as such. McQuillan (1) states that large numbers of Scottish people, perhaps as many as 100 000, were rounded up and transported to the colonies to be sold into slavery. The poor, homeless and irksome Scottish people were gathered – or simply kidnapped – to be sold for a great profit on arrival at their destination. Children were no exception.

1701-1750

In 1701 there is the first organised attempt at converting Africans to Christianity. However, this was mainly a side effect from attempts to strengthen the influence of the Anglican Church in general. Around the start of the 18th century, Henry Compton, Bishop of London requested Rev. Dr. Thomas Bray to report on the state of the Church of England in the American Colonies. Dr. Bray reported that the Anglican Church in America had “little spiritual vitality” and was “in a poor organizational condition”. On June 16, 1701, King William III issued a charter establishing the United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG) as “an organisation able to send priests and schoolteachers to America to help provide the Church’s ministry to the colonists”.(2)

The society’s first missionaries started work in North America in 1702. Its charter soon expanded to include “evangelisation of slaves and Native Americans.” By 1710, SPG officials stated that “conversion of heathens and infidels ought to be prosecuted preferably to all others.”

The target population was mainly the white colonist, but African slaves should also be Christianized whenever possible. All in all however, the impact remained rather limited and the entry of slaves in the Church was not widespread. White colonists maintained their “laisser faire” policy towards the religious and cultural value system of their labour force. Their first preoccupation was to make their labour force profitable; it was not until more than a century later that they would realize that saving the slaves’ souls would also contribute to those profits.

One of the missionaries who worked in America in the 1730′s was John Wesley, the founder of Methodism. “His preachments were underscored by the hymns of Dr. Isaac Watts, an English minister, physician, and composer whose music was livelier and whose lyrics closer to the vernacular speech of the day than what the stiff psalms of the day then offered.” (Humphrey, 1993:109). Watts’ hymns were particularly popular with slaves.

1750-1800

During the second half of the 18th century, there is a growing impact of the attempts at converting the African slaves, but it is far from general. Next to the Anglican church, also various dissenting sects (Presbyterians, Baptists, Methodists) start their soul winning activities, which in its turn stimulates the Anglican church to reinforce its efforts. The obstacles for an effective salvation remain however strong: the number of clergy men stays relatively limited and the geographical distances between plantations constituted a major impediment.

However, the interest of the Church to control the pagan culture of the slaves was consolidated. Bishop Porteus, who became the leading advocate within the Church of England for the abolition of slavery, noted in one of his writings:

“Many of the Negroes have a natural turn for music, and are frequently heard to sing in their rude and artless way at their work. This propensity might be improved to the purpose of devotion by composing short hymns set to plain, easy, solemn psalm tunes, as nearly resembling their own simple melody as possible. These might be used not only in church, but when their task was finished in the field, and on other joyous occasions. () Even instruction itself may in some degree be made an amusement (); that is by the help of a little sacred melody adapted to the peculiar taste and turn of the Africans; than which nothing would be more likely to secure their attendance at church, and to draw them off from their heathenish Sunday recreations abroad, by providing them with others full as agreeable to them, and much more harmless, at home”.

The quotation illustrates how the “natural turn for music” that was observed within the African slaves’ culture could be made a vehicle to appeal to their religious attitudes and was considered an efficient entry to bring them in the European culture by propagating “plain, easy, solemn psalm tunes”. At the same time, the gradual spread of the Christian/protestant value system “would carry with it a conscious or unconscious determination to curtail [the slaves’] native amusements, especially on Sundays. Conversion to Christianity would bring with it a greatly expanded acculturation involving language, dress, style of singing and disapproval of so called heathen practice.” (Epstein, 2003: 108).

Religious observance slowly replaced the frolicking. As the Sunday observance preached by Christianity spread, the restrictions on the “heathen” feasts and the markets held by the slaves on Sunday got stricter and stricter.

The address and confession of Abraham Johnstone, a black man, hanged in 1797, speaks for itself how the assimilation process of European values had set out (3):

“My dear brethern I earnestly pray ye, to be diligent and industrious in all your callings, manners of business and stations in life, be punctual, upright and just in all your contracts, engagements and dealings of what kind or nature soever (). Be decent in your dress and frugal in all your expences, for by that means you will provide for the wants of sickness and old age, refrain from the too great use of spirituous liquors a little is serviceable, but by all means beware of two much, for that irreparably injures the constitution, and cannot add to the enjoyment of those innocent pleasures and recreations necessary to ye as human beings and members of society.–But above all my dear friends avoid frolicking, and all amusements that lead to expence and idleness for, they beget habits of dissipation and vice, and lead ye into many inconveniences, a few of which I will endeavour to point out as the most immediately attendant on such a manner of life.”

With this assimilation process, the foundations were being laid for the development of the Afro-American spiritual, one of the later ingredients for the emergence of the blues.

However, at the eve of the 19th century, the situation remains very heterogeneous and we should refrain from too much generalisation based on fragmentary observations of the information available today.

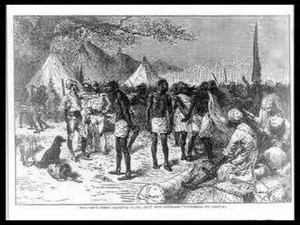

D.L. Fountain (2010) warns us against the widely accepted interpretation of the role that Christianity played among slaves in the South before the Civil War. This interpretation holds that an Africanized Christianity was a cornerstone for the culture of the slaves. This Afro-Christianity enabled believers, so it is supposed, to persevere and hope for deliverance from bondage, just as the Israelites’ faith had in the Old Testament. This scholar underlines that in fact there is little evidence in the historical record to support this supposition. On the contrary, evidence suggests that most slaves in the antebellum era were not Christians. An Afro-Christianity did not sustain slave communities, he says. Such communities were religiously diverse, “a kettle of remembered African myths and rituals, not Christian”. “Frolics” of music, dancing, gambling and wrestling remained more popular on Sunday than church. The great conversion came only after the Emancipation Proclamation. At the same time he cautions that his interpretations aren’t definitive, but are only suggestions.

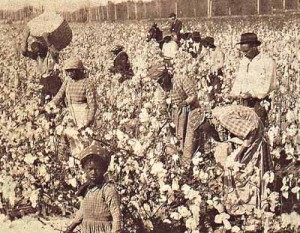

The role of Afro-Christianity down on the plantation needs thus much more exploration. This will help us also to shed more light on that part of the timeline which runs from slavery to the blues. An exploration which needs to include the aspect of the regional variations and the migratory inter regional movements. Let us not forget that by 1807 when the Slave Trade Act was passed by the British Parliament, making the slave trade illegal throughout the British Empire, an important shift was already taking place in the regional spread of the slave population. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 caused a massive growth of the production of cotton and slavery began to develop even deeper roots in the South. Particularly the deeper South became more dependent on plantations and slavery, making plantation agriculture (cotton) the largest sector of the Southern economy. In parallel with the increase in cotton production, the number of slaves rose from around 700,000, before, to around 3.2 million in 1850. This happened in parallel with a decline in the importance of the tobacco culture in Virigina which had shown a production pace that had exhausted the rich soil of the region. A commentator observed in 1835 that in Virginia “many intelligent planters, foreseeing the inevitable course of things, are by degrees abandoning the culture of the plant, and giving increased attention to the growing of wheat and the improvement of their over cropped lands”.

The relation between on the one hand the variation by region and time of the economic and labour systems in which slaves were exploited and on the other hand the development of their cultural system remains a topic which requires much more investigation. Such an inclusive approach has for instance been applied by D.A. Pargas (2008) who has highlighted the differences in slave family life and structure between Virginia, South Carolina and Louisiana. The nature of the regional agricultural systems and their corresponding daily and seasonal labour patterns clearly defined the boundaries and opportunities for the development of family life. I am very keen on finding more literature which establishes such links with the entertainment and musical development of the African American population.

_________________________________________________

SOURCES and FOOTNOTES

_________________________________________________

(1) http://heritage.caledonianmercury.com/2010/11/09/the-hidden-scots-victims-of-the-slave-trade/001584

(2) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USPG

(3) http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/johnstone/johnstone.html

– http://debate.uvm.edu/dreadlibrary/marcus.html :

Harmony and Howling — African and European Roots of Jamaican Music – Tim Marcus

– http://web.northnet.org/minstrel/scottish.slaves.htm

-The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History – Richard W. Bulliet et al. (2010)

– Real pirates: the untold story of the Whydah from slave ship to pirate ship – Barry Clifford et al., 2008

– http://www.news-record.com/blog/63640/entry/108498

– D.L. Fountain – Slavery, Civil War, and Salvation: African American Slaves and Christianity, 1830 – 1870 (2010)

– Damian Alan Pargas, Weathering Different Storms: Regional Agriculture and Slave Families in the Non-Cotton South, 1800-1860, Leiden, 2008 (Phd)

– D. J. Epstein : Sinful tunes and spirituals, 2003

– Mark A. Humphrey : Holy Blues, in : Nothing but the Blues, Lawrence Cohn, 1993