Sing Us Back Together: Ken Burns’ ‘Country Music’ and What it Says about America

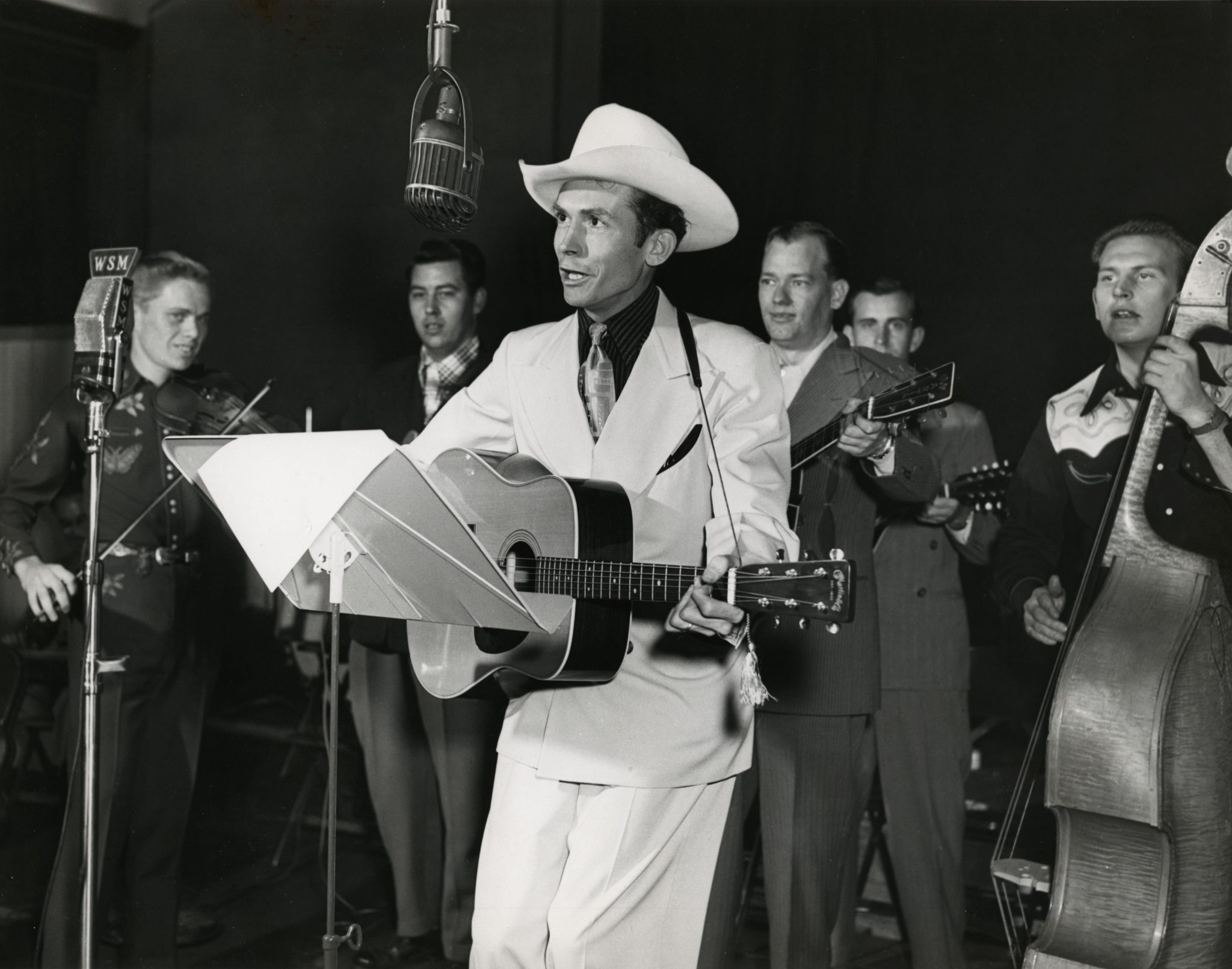

Hank Williams at the WSM radio studio in Nashville, c.1948. (Courtesy of the Les Leverett Collection)

Ken Burns documentaries typically rely on scholars as narrators. Obviously, Burns’ crew couldn’t talk to a member of the 1908 Chicago Cubs, making the game’s historians the best sources for the 1994 series Baseball. Likewise, for a modern topic like Vietnam, experts offered some of the best insight on a polarizing time in American history.

From left, “Country Music” producers Dayton Duncan, Julie Dunfey, and Ken Burns (photo by Evan Barlow)

But once Burns and his co-producers Dayton Duncan and Julie Dunfey began work on the eight-part, 16-and-a-half-hour series Country Music, it became obvious that the genre’s history could be told just as well by the musicians themselves.

“Normally on a subject like this, we would reach out and have dozens of academic advisers, as we had just done with a couple of dozen with Vietnam,” Burns says. “What we found early on is that with country music, the people themselves understood the history. They protected it.”

Aside from a few brief appearances by Bill C. Malone, the author of Country Music USA, country music scholarship’s bible for over 50 years, the series builds off 101 interviews with artists, producers, and industry insiders: 20 of which passed away since filming began more than eight years ago.

Many of these narrators are veterans with first-person stories about heroes, band leaders, and kinfolk. Expert practitioners include Kathy Mattea, Ricky Skaggs, Vince Gill, Dolly Parton, and the family circle’s unofficial genealogist, Marty Stuart.

“Marty, more than anybody else, and also Vince are like Wynton Marsalis in jazz,” Burns says. “They are people that have their own work and their art that projects it forward, but they also know where they came from. It’s very important for them that people not forget where they came from. So, Marty can talk about Jimmie Rodgers, he can talk The Carter Family, he can talk about Hank Williams, he can talk about Johnny Cash, he can talk about Bill Monroe and do it with an intimacy. In many cases, he knew them. He worked for Johnny, he knew Monroe really well, and he worked for Flatt.”

In the series, which premieres on most PBS stations on Sept. 15, artist interviews are interspersed amid a historic narrative featuring rare photos, unearthed archival footage, and at least one well-researched fact that caught even Stuart off guard.

“Marty, you know, met his wife, Connie Smith, when he was young,” Mattea says. “His mom took him to see her at a local fair when she was touring. He looked at his mom and said, ‘I’m going to marry her someday.’ He’s told that story for years, with him being 12 years old when he saw her. In the documentary, they say he was 11. He came to Dayton and said, ‘You got that wrong, man. I was 12.’ Dayton said, ‘Well, we went back and looked up the dates, Marty, and it was a month before your 12th birthday, so technically you were 11.’ That’s the kind of people we’re dealing with. They really care about details.”

Legends and Family

Merle Haggard signs one of two Martin D-28 guitars autographed by interviewees for “Country Music.” The interview took place in 2014, and Haggard passed away in 2016. (Photo by Jared Ames)

As the only co-producer with prior interest in country music, Duncan relished the chance to meet legends who’ve since rested high on that mountain, such as Guy Clark, Cowboy Jack Clement, Ralph Stanley, Mel Tillis, Mac Wiseman, and one of the series’ standout contributors, Merle Haggard.

“Interviewing Merle Haggard has got to be one of the highlights of my life,” Duncan says. “I mean, there he is. He’s one of the greatest American songwriters, period, full stop. A great singer and passionate about country music history. He appears in every single episode of our film because he wanted to talk as much about Jimmie Rodgers or Bob Wills or Maddox Brothers and Rose or the art of songwriting or Lefty Frizzell as he did about his own remarkable life and career.”

Burns’ crew missed out on one legend whose influence becomes undeniable after the series makes it into the 1960s.

“The biggest one was George Jones,” Burns says. “We had sort of an agreement to do it. We’d been in contact, and we were coming into Nashville it seemed like every other week or at least once a month. We were going to do him, and then all of a sudden, his people were suddenly silent. We found out why.

“But you know,” Burns adds, “I was as proud of the scenes about George Jones as any in the film. They’re so poignant and so well done. We didn’t have Abraham Lincoln for the Civil War, but we did okay with that, you know what I mean?”

For Jones and other legends with complicated backstories, the documentary avoids cold-hearted jokes about lawnmower rides to the liquor store, opting instead to paint a fuller and fairer picture.

“There are undertones, but you don’t need to go one way or the other,” Burns says. “You know, whether it’s No-Show Jones or Johnny Cash knocking out all the footlights at the Ryman or some of the problems that Hank had in his last days with drugs and alcohol. You can tell all of that, and it doesn’t take away from them. They are who they are. I’d just (ask) people who want to use people they don’t know as kind of weapons or examples, what do you do in your own family when you’ve got somebody with a problem? Do you kick them out? No. You just say that they’re one of ours. Let’s take care of them.”

Although the series’ timeline ends in 1996, three younger names offer their old-time and bluegrass music expertise: Dierks Bentley, Rhiannon Giddens, and Old Crow Medicine Show’s Ketch Secor.

“What’s interesting is that with the exception of Willie and Merle and a couple of other people, our first episode is mostly commented on by the youngest people,” Burns says. “The oldest period that we cover is known best by Ketch and Rhiannon. They know Fiddlin’ John Carson and when he played. It was really, really great to have them. And, of course, they come up at many places in our story.”

While watching an early draft of the first episode, Mattea was floored by her younger peers’ contributions.

“There’s that lovely opening of Ketch Secor playing an old-time fiddle tune that’s probably 100 years old,” she says. “He’s a young ’un, and he knows the bloodline of the music that he’s playing. (The producers) said that was a fascinating thing they found, that country music is passed from generation to generation unlike anything else they’ve worked with.”

Regardless of age or genre affiliation, each country, bluegrass, and Americana artist featured jumped at the opportunity to discuss the legends, songs, and stories at the heart of the music.

“To me, it’s such a spiritual, godly thing,” Skaggs says. “Of the 10 Commandments, the only commandment with a blessing is to honor your fathers and mothers. That’s exactly what we’re doing in this whole documentary. We are honoring elders that came before us. We’re telling funny stories, which is part of it, but we’re sharing the importance of what these people did and the music they made and how we’re standing on that.”

By telling an ambitious story though the insight of the artists themselves, Burns’ film shatters misconceptions about the backgrounds and values of some pre-Dixie Chicks country acts and their fanbases.

“A lot of these things that are surprising to some people, like the African American interconnection in country or the strong women in country, we didn’t put those in to try to make a point,” Duncan says. “We put those in because that’s what we discovered when we were doing the exploration of it. Not to include those stories would be historical malpractice, I think.”

Drop in the Bucket

Despite the series’ length and attention to detail, the final product represents just a fraction of the hours of footage Burns’ crew collected, and then donated to the Country Music Hall of Fame. Even the best documentarian in the game might’ve skipped your favorite song or skimmed through a favorite singer’s career. If that’s the case, check the companion book’s glossary before directing hate mail to Burns’ Florentine Films. (Read ND’s review of the book here.)

“Every time a scene drops onto the editing floor and I start to weep, Ken will pat me on the back and say, ‘You can still put it in the companion book, Dayton,’” Duncan says. “It gives me the opportunity to tell a fuller story. There’s much more information and more stories in it than we’re able to squeeze down into the script of a 16-and-a-half-hour series. One two-hour episode is about 42 pages of script in the way that we format things. Take that times eight and it’s still quite a bit, but it’s a little over half of what we can put in the book.”

Duncan hopes that gaps perceived by viewers inspire reading, research, and trips to the local record store.

“I think of our films not as the final word but the opposite of that,” he says. “It’s an introduction to millions of viewers to say, ‘Hey, this is something that we’re excited about. We think these are great stories and important stories.’ Or, in this case, there’s terrific music. And that will inspire people or nudge them to go out and read more about that particular topic or to go to places where the history took place or, in this case, listen to more of the music. Even though we’ve got 580 music cues in our film, it’s still just a drop in the bucket.”

For Burns, his newfound appreciation for country music’s tight-knit community makes him crave similar harmony in the nation he chronicles on film.

“All I’d love to do is expand everyone’s notion of family,” Burns says. “I work in this privileged space between the lowercase, two-letter plural pronoun ‘us’ and its larger capitalized version, ‘the US.’ That’s where I work — In between those spaces. The majesty of the US but also the intimacy of us. If people would understand that the US is also us and us is also the US, there’d be far less acrimony. There’d be far less division. There’d be far less tribal stuff going on. I think country music is one of the ways we can sing us back together.”

Ken Burns’ Country Music begins airing on most PBS stations on Sept. 15 at 8 p.m. ET — check local listings. The series will be available on DVD and Blu-Ray on Sept.17, and Spotify is featuring the Ken Burns Country Music Experience with 48 songs and video outtakes from the documentary’s interviews. To comment on this or any No Depression story, please drop us a line at letters@nodepression.com.