Robert Earl Keen – Can you patch together a feeling that’s going to stick with somebody ten years from now?

So here’s the setup: “Two Aggies walk into a bar…”

Aggie jokes are a staple of humor in Texas, but the two A&M alumni who embraced in the lobby bar of the Four Seasons in Austin early one Thursday morning in mid-March could luxuriate in the fact that the joke was not on them. One of the two men was Robert Earl Keen; the other was his college friend and musical colleague Lyle Lovett. Both men’s hair was touched with gray, and both have come an improbably long way since they used to sit and swap songs on the front porch of Keen’s student quarters on Church Street in College Station.

Keen was on hand to plug a forthcoming album, What I Really Mean. During the week that South By Southwest takes over the city, radio station KGSR beams its morning show from the Four Seasons bar and invites a slew of musicians to sit in and perform. For his part, Lovett didn’t have anything to sell; he just enjoyed hanging around the broadcasts all week and kibitzing with the DJs.

Keen came away from A&M in 1980 with an English degree and the rudiments of a self-taught musical education. Discovering he could make music was like walking through a door into a new room.

In 1983, he won a Best New Songwriter award at the Kerrville Folk Festival and followed that up by taking Best Songwriter honors in the Austin Chronicle Reader’s Poll. He released his debut album, No Kinda Dancer (funded by investors to the tune of about $4500), independently in 1984. It contained his first signature tune, “The Front Porch Song”, co-authored with Lovett and chronicling their feckless Aggie days. He signed on with Sugar Hill and released The Live Album (which documented Keen’s well-deserved reputation as a raconteur), West Textures and A Bigger Piece Of Sky from 1988-93.

His songs were (and are) populated with charismatic losers, idealistic drunks, sullen misfits and star-crossed lovers — as rowdy and vivid a cast of characters as James Joyce might have assembled (if Joyce had grown up in Texas dipping snuff and singing “The Aggie War Hymn” before football games). One song about desperados on a full-throttle run down a dead-end street, “The Road Goes On Forever”, became the most improbable party anthem in Texas music history (and the title track of an album by Willie & Waylon & Cash & Kristofferson, aka the Highwaymen).

Two major-label albums, 1997’s Picnic and 1998’s Walking Distance, helped give him a national profile, as did ceaseless touring. Audiences responded less to his serviceable baritone voice (“People get used to my voice,” he said wryly one night outside a bar in Ciudad Acuna, Mexico. “But then, people get used to artichokes too.”) than to his vivid characters and hardscrabble stories.

What I Really Mean, due May 10 on Koch Nashville, has more than its share of those, and it seems notably darker in tone and subject matter than its last couple of predecessors. Allegorical tales such as “The Traveling Storm” share space with surreal portraits such as “The Great Hank”, lovers’ laments like “For Love” and “Broken End Of Love”, and yet another of Keen’s tongue-in-cheek Mexican travelogues, “A Border Tragedy”.

Robert Earl Keen is a lifer, and his passion for his life’s work is nowhere near being quenched.

I. THE LAST TIME I FELT LIKE THIS WAS FOR NEIL ARMSTRONG

NO DEPRESSION: How did 2004 treat you?

ROBERT EARL KEEN: We had a spectacular year as far as touring goes. Had lots of fun, did some Dave Matthews dates. And we did that Lance Armstrong thing down there in Austin [the downtown blowout celebrating Armstrong’s sixth straight Tour de France victory]. I was ready to put down the guitar and say I don’t ever want to do another gig, ever — that was as good as it gets. All that swelling with pride and happiness sort of thing. And for all the right reasons. I was thinking that the last time I felt like this was for Neil Armstrong. When those yellow lights came on [the state capitol building was illuminated with yellow spotlights, symbolic of the Tour winner’s yellow jersey] and Lance walked onstage, I almost cried.

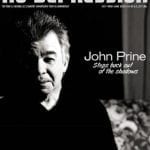

We played this marvelous festival last year called the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival, in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. Three days, 70,000 people every day. And we were the first act asked back for next year, out of Emmylou [Harris] and Gillian [Welch] and John Prine and Nick Lowe.

ND: Do you get a different buzz from doing something like that than singing for 20,000 beer-drinking Texas college kids at Willie’s Picnic?

REK: It’s somewhat different. That [San Francisco] audience, as large as it was and as big as it was, they’re there more on the music fan side, not the event fan side….Sometimes you go out there and get the buzz just from the people power. That’s our thing, we always do a different set, to see what’s going to work. As far as versatility, we’ve got a pretty broad spectrum — we can go from extremely quiet and almost painfully poetic to scream and yell and drink more beer.

ND: Do you think of yourself as a different performer when you cross the state line?

REK: No…My big axe to grind about this whole deal is that I’m getting tired of always getting locked into this “Texas singer-songwriter” thing. And that is not to say anything disparaging about those guys. It’s great company. But I wanna tell you — I’m standing toe-to-toe with Elvis Costello or John Prine or Dylan or any of those guys. I’m writing these songs, they kick ass, they completely translate anywhere and…I’m there.