PRINT EXCERPT: Johnny Cash’s Career-long Love Affair with Train Songs

EDITOR’S NOTE: Below is an excerpt from a story in our Summer 2018 print issue “(im)migration” You can read the whole story — and much more — in that issue, here. And please consider supporting No Depression with a subscription for more roots music journalism, in print and online, all year long.

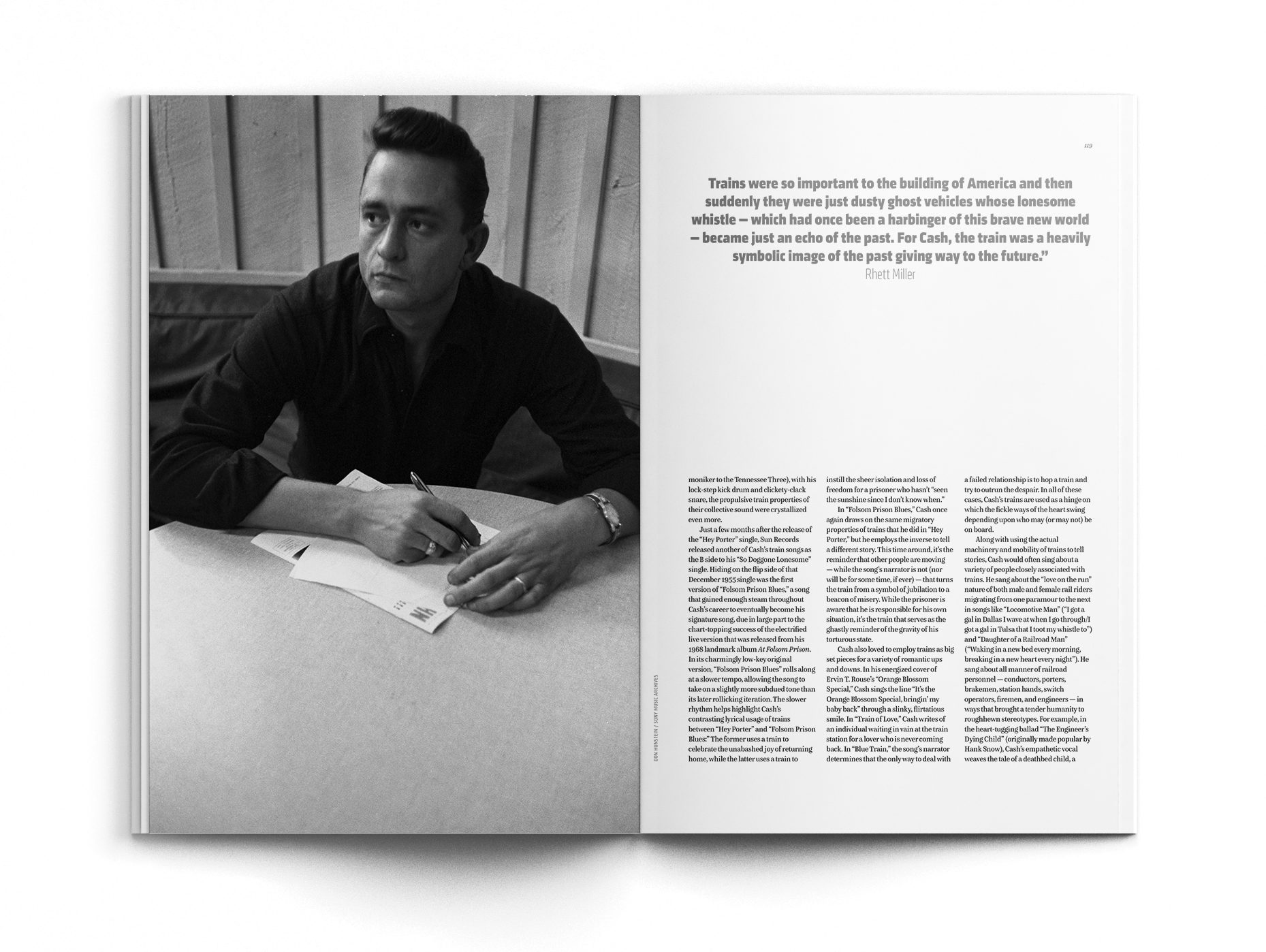

As one of the most prolific entertainers of the modern era, Johnny Cash sang about a vast array of topics throughout his legendary half-century career. From his earliest recordings for Sun Records in the mid-1950s all the way up to his final recording session just a few weeks before his death in 2003, Cash’s impressive catalog includes the release of over 150 singles and close to 100 full-length albums. While it seems like there was no subject deemed off limits for The Man in Black, he did seem to return to a few favorite motifs again and again. His ingenious ability to draw a new bucket from the same well is evident in his numerous concept albums (Bitter Tears, Sings the Ballads of the True West, America, The Rambler), his thematically linked compilation sets (Love, God, Murder and the later released Life), and his litany of gospel and Christmas records.

But of all the oft-visited material in Cash’s expansive musical inventory, there’s one topic with which he seems to have logged the most sonic mileage: trains.

From his very first recording with the Tennessee Two (the 1955 single “Hey, Porter”) to the very last song he ever wrote (“Like the 309,” posthumously released on American V: A Hundred Highways in 2006), trains were a constant presence in Cash’s career. Whether it was a passing reference in a single lyric, the lead character of an entire song, the central thread of a concept album, or the overarching theme of a multi-disc box set, Cash called on trains in a myriad of ways to serve a wide variety of storytelling purposes. Writing about Cash’s connection to train songs for a Vanity Fair profile of his American V: A Hundred Highways album, writer David Kamp said: “Trains were in Cash’s veins, insinuating their boom-chicka-boom rhythms into his early records … and serving him lyrically as metaphors for adventure, progress, danger, strength, lust, and American Manifest Destiny.”

The secret to Cash’s multifaceted approach to train songs was not to rely solely on their literal characteristics and usages (though he masterfully did that in ways few others could), but also to mine them for their metaphorical, spiritual, and existential value. The idea of trains being used for migration in all its forms — geographically moving from here to there, historically moving from past to present, philosophically moving from one concept to the next, emotionally moving from one state of being to another, and metaphysically moving from life to death — was a densely-layered perception that Cash understood and synthesized into his songs in a way that contributes greatly to his overall creative legacy.

“Johnny Cash owns the train song genre,” Rhett Miller emphatically states. For the last 25 years, Miller has fronted the pioneering alt-country band Old 97s, whose name was derived from “The Wreck of the Old 97” (one of the many bygone train ballads Cash popularized throughout his career). “In a lot of ways, train songs are the ultimate distillation of the fight-or-flight response. They’ve got all the violence of the fight and all the forward motion of the flight, and the songwriter is trying to turn that into something that equates to freedom. It’s this weird magic trick that we all try to do, and Johnny Cash was one of the best to ever do it.”

In analyzing the breadth of Cash’s deft, multipurpose usage of train songs, it seems that almost all of his rail-themed pieces (with a few exceptions) find him assuming the role of one of these four categories — storyteller, historian, sentimentalist, or existentialist. While many of his train songs have overlapping characteristics within those four categories, there is usually a singular standout quality that helps identify which category a song fits into most fully.

Cash’s first experience with a train song coincided almost immediately with his first notable experience in the music business. During his initial audition for Sun Records, Cash led his Tennessee Two backing band (hobby musicians Luther Perkins on guitar and Marshall Grant on bass) through a few gospel numbers that failed to pique the interest of famed producer Sam Phillips. As the story goes, Phillips challenged Cash to scrap the gospel routine and try his hand at something a little more raucous and upbeat; something more along the lines of Phillips’ newest protégé — a young rockabilly singer named Elvis Presley. Accepting the charge, Cash came back to Sun Records with the newly penned “Hey Porter,” and Phillips promptly recorded and released the train song (along with “Cry! Cry! Cry!” on the flip side) as Cash’s debut single on May 21, 1955.

Immediately, “Hey Porter” showcased Cash’s iconic ability to tell a full-fledged story in a three-minutes-or-less song. Drawing from his recent experience returning home from being stationed in Germany while serving in the Air Force, “Hey Porter” finds Cash embodying an enthusiastic railcar rider who is homeward bound and excitedly longing to “set [his] feet on Southern soil and breathe that Southern air.” Though we only get a short snippet of the narrator’s journey, Cash places the listener directly among the other passengers by weaving rich narrative details into each lyric. By the time he sings the line “I smell frost on cotton leaves and I feel that Southern breeze,” listeners feel like they’re experiencing the exact same sensations — the mark of a vivid storyteller.

For all of the fictional story songs with made-up characters and commonplace train-themed activities that Cash unfurled over the years, he also wrote and sang an impressive number of songs about literal, real-world characters, rail lines, and events. An avid historian, Cash loved to use his musical platform to bring the past into the present in a way that was heartfelt and genuinely delivered. He seemed to have an even deeper fondness for doing this when it could be done within the context of his treasured train songs.

One of Cash’s favorite methods of operating as a historian was to pull from the rich tradition of songs that mentioned specific trains and rail lines by name. Cash started this creative choice with his very first full-length album, 1957’s With His Hot and Blue Guitar, which featured his takes on “The Rock Island Line” (based on the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railway) and “The Wreck of the Old 97” (based on the 1903 Southern Railway mail train disaster). With both tracks being traditional folk songs of unknown authorship, Cash joined a long line of song interpreters who tasked themselves with the creative responsibility of passing along songs that had been handed down to them while trying to add a little of their own sonic spice to the mix. Cash would continue to build this train song traditionalist section of his catalog by recording versions of other hand-me-down, real-life rail tunes, such as “Wabash Cannonball” (based on the Wabash, St. Louis & Pacific Railway express train), “The City of New Orleans” (based on the Illinois Central Railroad’s passenger train of the same name), “The L&N Don’t Stop Here Anymore” (based on The Louisville & Nashville Railroad freight train), and “Orange Blossom Special” (based on the winter-only Seaboard Air Line Railroad passenger train that ran from New York City to Miami). As Cash’s confidence and musicianship grew, he would often try to add something new to these traditional songs, such as swapping out the bluegrass fiddle sections of “Orange Blossom Special” with a lively harmonica (impressively played by Cash himself) and saxophone (played by “Yakety Sax” co-writer Boots Randolph).

When Cash wasn’t using trains to tell vivid stories or to craft musical history lessons, he would often utilize them as nostalgic touchstones by which he could reminisce about his family and his childhood growing up in the rural South. Much like he used a hymnbook as an oft-repeated anchor when singing songs that connected him to his mother, Carrie Cash, he used trains in songs that connected him to his father, Ray Cash.

One of the finest examples of this is Cash’s song “Ridin’ on the Cotton Belt” from his 1977 album The Last Gunfighter Ballad. Opening with one of his signature spoken word narrations, Cash outlines a bit of the story that inspired the song (he took his parents on a bicentennial homecoming trip to Cleveland County, Arkansas, and his father told him hobo stories all day long) and then explicitly states, “Sometimes the songs I write sound like I’m talking about myself, but actually, in some of these songs, especially this one, I’m writing it about my daddy.” Echoing a bit of the “excitedly returning home on a train” feeling that Cash embodied for “Hey Porter” more than 20 years prior, “Riding on the Cotton Belt” finds Cash putting himself in his father’s “working hobo” shoes on a trip back home after making some money for his family. Of course, one of the interesting differences between “Hey Porter” and “Riding on the Cotton Belt” is in the nature of the song narrator’s passage; where “Hey Porter” involves a ticketed passenger, “Riding on the Cotton Belt” celebrates Ray Cash’s ticketless, carhopping means of travel with lines like “Jumping off the Cotton Belt ain’t easy when she’s going forty per” and “I got a few new cuts and bruises but this old working hobo’s made it home.”

And finally, one of Cash’s favorite uses for train songs, especially in his later years, was as a metaphorical device to sing about mankind’s existential migration through life and metaphysical migration from life to death. Cash employed this type of imagery in both sacred and secular ways throughout his career on songs like “This Train Is Bound For Glory” and “Life’s Railway to Heaven,” but it was during the American Recordings sessions of his later years that Cash truly turned his love for train songs into an existentialist exercise. When lined up against the vast catalog of songs he amassed during his almost 50-year career, it’s hard to paint a more poetic picture than Cash singing this closing line of an old train song as his very last recorded lyric mere weeks before making the final migration on his own train bound for glory.