Laurie Anderson, Cáit O’Riordan, and Paul Muldoon’s Picnic

Since 2014, Paul Muldoon has hosted a series of evenings at the Irish Arts Center in New York. Muldoon’s Picnic is named for a popular New York City entertainment of the 1880s, itself borrowing a name from a song popular in New York in the middle 1870s, “Muldoon The Solid Man.” The sometimes ramshackle, audience-participatory, and self-scrutinizing joys of both the entertainment and the song must have appealed mightily to the Picnic’s eponyous organizer in the naming. A New York Amusement Gazette from 1887 lists “Muldoon’s Picnic” among the “Cheap Theatre” options including baseball games, racing at Coney Island, a diorama and performance of the battle of Gettysburg in (appropriately) Union Square, and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. A student newspaper from 1881 prints the complaint from one young patron that “the trained donkey was the best actor,” so you can get a sense of the variety available at the Picnics of a hundred and more years ago.

Paul Muldoon’s Picnic is quite varied itself — though featuring, as yet, no trained livestock or other animals. It is based upon vaudeville revues and music-hall shows, those in turn borrowing from Elizabethan theater days. If you went to see a new Shakespeare play at the Globe in the late 1500s, you did not go soberly and in the expectation of immortal literature. You went early and saw the warm-up acts, jugglers, and musicians and comedians. They’d be back at the interval, along with orange and apple sellers and vendors with bags of nuts, which spectators enjoyed, noisily, throughout the play. Movies used to be screened like this, too, if you can recall: newsreels first, and comic shorts, before live music and the main event. It is an exceptionally fine idea for an evening out; three cheers for Muldoon for having it, in the midst of all else he does (poet, literary critic, Princeton University professor, poetry editor of The New Yorker).

The house band for Muldoon’s Picnic always varies, and you never know who’ll be joining in, unannounced. In 2004, Muldoon, with Nigel Smith (also a Princeton professor, of Renaissance literature), founded Rackett, which changed members (though Smith and Muldoon remain) and reincarnated as The Wayside Shrines in 2010. From The Wayside Shrines to the present iteration, joyfully named Rogue Oliphant, the Picnic band(s) have been fortunate to have Chris Harford on lead guitar and vocals. You don’t know Harford and his music? You should. For decades he has been a constant, and popular, visual artist, singer, guitarist and songwriter on the New Jersey/New York music scene (he, too, hails from Princeton). His own current work with his Band of Changes is exciting and lyric, and he is fond of inviting good friends to sit in at the Picnics. One evening last year, when I was lucky enough to be there, a slight man with a mass of curly hair strolled on stage with the band and picked up his fiddle: David Mansfield. This time Dave Dreiwitz of Ween and Robbie Seahag Mangano were here to sit in with Rogue Oliphant.

Last night, poems were read, and read well, by Muldoon himself (herald the rhyme of “gin and campari” and “jamboree,” friends) and by Timothy Donnelly. The musical guests were Mark Mulcahy, Cáit O’Riordan, and Laurie Anderson.

Mulcahy, formerly of Miracle Legion and Polaris, is a vivid performer who sang two songs in honor of his late mother, for it was her birthday. “She’d be delighted that I’m celebrating it in an Irish club,” he announced. The lyrics were sad, but the tunes danceable – a tone thereby being set for the evening. You couldn’t sit still, but it was incumbent upon you to listen: for my money, the best kind of music, when the words and the sound complement and complete each other.

The eager audience at a New York Irish venue all knew O’Riordan like an old friend, from thirty and more years ago, from her days as a founding member of The Pogues, and her American tours of the mid-1980s with Elvis Costello, who was once her husband. She looks as if she is barely in her thirties today, slim and elegant, with a smooth long pageboy haircut: far cries away from the spiked punk that was the seventeen-year-old Pogue. And then she smiled a radiant, genuine smile from the stage and announced she’d be singing a song by a dear friend, too soon gone. Philip Chevron’s “Kitty Ricketts” (1979) predates their days as Pogue bandmates, but seems made for her, and she sang it from here to eternity – a soaring performance that I sincerely hope was recorded. She bowed at the end to the applause, and took over the bass for several other songs. I heard The Pogues many times, but never when she was with them. The grace note of their best album, Rum, Sodomy & The Lash (1985) is O’Riordan’s lovely cover of the sharp-edged air “A Man You Don’t Meet Every Day.” When she said, “This is an old song,” I confess to a yelp of pure happiness that I wish I hadn’t stifled. O’Riordan sang it sweetly as ever, yet with the violence the often cruel song demands – clasping the mic in a two-fisted, double-forearmed grip on the lines about shooting the dog. The “be easy and free when you’re drinkin’ with me” sounds less like an invitation than a serious caution. You felt the mad, bad energy of the words under the gentle melody that made, and makes, the song a punk classic in her hands.

Laurie Anderson had been scheduled to appear at an earlier Picnic, but had to take a raincheck until this rainy Monday before St. Patrick’s Day. In introducing her, Muldoon spoke of her not only as a performer, but a maker of instruments for her art – what she needs to say what she wants to say, she creates. He also deployed the word “iconic,” lamenting its overuse in these hyperbolic days – for surely it was made for Anderson.

She had been in the audience, listening to the show so far, and walked up the short aisle to settle behind her – how to say? Computer, sound system, keyboards, synthesizers? behind her instruments. No, among her instruments is more accurate. Clad in black sweats and black tennis shoes with vivid orange soles, and a little maroon wool hat with yellow circling stripes, she was slight and small and filled up the room, the building, from the first moment she clipped her tiny tape-bow violin over her shoulder. By the time she set it down and turned to the technology in front of her, you wanted to hear her speaking voice, but also did not want the music to stop. No worries – with Anderson, it never does. The sound is part of the story.

Storytelling is what she does, and does best of all. Her stories are rooted in the America she grew up in, its literature and art and culture – and in what she foresees of our days to come. Imagine a little girl, barely a teenager, running for student government in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, in the late 1950s. Imagine her writing to Senator Jack Kennedy for advice about how to run a campaign. Anderson engaged the audience with her eyes, icegreen yet warm, as she spun out the start. She smiled indulgently, an adult’s smile, at that girl-version of herself, but in the deep dimples is pride and achievement, too: Anderson is still that girl, as well. Kennedy wrote her back – “a long letter….with bullet points,” Anderson said, as we laughed. The most salient thing he suggested? Get to know your peers, spend time with them, and figure out what they want. And then “promise them anything.” Anderson paused. She did not write him back to thank him for awhile, and when she did, she apologized. She’d been very busy, because she had won the election. “A couple of weeks later, a special delivery truck came up our street.” No one on the street – possibly in the town – had received a special delivery before. Anderson received a telegram of congratulations from Senator Kennedy, and a box that contained a dozen red roses. The local paper ran a story about it. “Every woman in the town,” she said softly, “was in love with Jack Kennedy.” The soundtrack was the sound of nostalgia, sweeping strings and a light swing beat.

Sounds and stories sometimes end happily ever after – if they ever really end. Everyone listening knew what thirteen-year-old Laurie did not: what happened to Jack Kennedy after he won his next election, and became President, and lived for only three short years more. Anderson’s songs and stories had personal starts and universal endings. A tale of heading back to the land, to live with an Amish family and help out in the gardening and household chores, had presentiments of disaster even in its pastoral framing: Anderson’s eyes glinted danger, even as she smiled, at the prospect of a people who, in critical ways, haven’t progressed “since the sixteenth century.” The rains came, and the time was dire, trapped in an Americana huis clos around the kitchen table with a crying three-year-old and bitterly arguing parents. Grandmother came to visit one day, and her litany is as persistent and insistent as the child’s crying: “kiss me,” she keeps petitioning the little boy. Finally he agrees, but only when they are all in the living room. “This seemed safe,” Anderson quips, “since we’d all been around the kitchen table for days, and days.” Yet into the living room they go, and watch, audience, as the child realizes he’s been had, that now it’s time for “his part of the deal.” He approaches his grandmother. “A tiny child, who has just learned” Anderson pauses for a two-beat “to kiss without affection.” Collectively, we reacted, little sounds of recognition, understanding, sorrow. And again, as, in a voice distorted to sound like a middle-aged man’s, she spoke about politics and its disappointments. “Dear Senator Kennedy,” in the child’s voice, gave way to a growly, bass-baritone “Dear Donald Trump.”

Anderson closed with symphonic elegance on a terrible subject: a house consumed by fire. Was she analogizing this to America today? Of course she was. The collective and the personal conspired to take your breath away. “If your house were on fire, what would you take out? Childhood pictures? Furniture?” We were all thinking, wondering. Books? Records? Odd family heirlooms? Anderson brightened, smiled again, and said quietly, clearly, “I’d take the fire.”

All I could hear in my head was that line until the end of the show. Anderson returned, then, to play her violin in the grand finale, which was O’Riordan and Mulcahy in a rollicking, festival duet of Muldoon’s “Off The Hook.”

Epic figures in the music world, and internationally acclaimed writers, were both on stage and in the audience last night at the Irish Arts Center. As Muldoon said in his introductory poem, the Picnic is a place “to see and be seen.” Last night, to be a seer was more than enough – to be there to look on and listen, learn and laugh and leave in a whirl of stirred-up thought and emotion, as happy as could be.

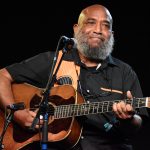

Rogue Oliphant image via Paul Muldoon