John Prine – To believe in this living

Prine, who overcame his initial disinclination to co-write songs to become the most openly collaborative of the great singer-songwriters — he’s shared credits with everyone from Goodman and John Mellencamp to Bobby Bare and Lee Clayton to a stable of regulars including Sykes, McLaughlin and Roger Cooke — produced Fair & Square himself, along with engineer Gary Paczosa. Though he has a co-producing credit on other Oh Boy releases, he considers this his first real effort at the helm. Working with his regular accompanists, guitarist Jason Wilber and bassist Dave Jacques, and old hands including Phil Parlapiano on accordion, organ and piano and Dan Dugmore on steel guitar, Prine arrives at such a natural, spacious, dare we say organic sound, you wish he had gotten serious as a producer before.

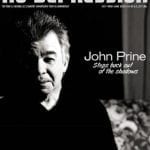

As a singer, Prine sounds freer and more relaxed than ever. Whereas the young John, beholden as he was to folk tradition, could sound a bit stiff and sober even when cracking wise, the older John has grown into a living-room kind of voice, where there are all kinds of crannies for his listeners to find comfort.

It wasn’t just living that altered his pipes. An uncommon form of cancer had a say in it as well. In 1998, after he had started making In Spite Of Ourselves, an offbeat series of country covers featuring duets with the likes of Iris DeMent, Melba Montgomery and Trisha Yearwood, he found out that the bothersome lump on his neck that doctors had dismissed as nothing was in fact something. Having seen Goodman stave off leukemia for years longer than anyone said he could (he died in 1984), Prine wasn’t scared by the disease, but he was unsettled by the fact that no two physicians could agree on what to do about it.

He was saved from manic doubt by an out-of-the-blue call from Knox Phillips, who had produced Prine’s 1979 album Pink Cadillac with his brother Jerry and famous father Sam. Having heard through the grapevine about Prine’s condition and his frustrating trials, he directed him to a health center in Houston where he’d had his own neck cancer successfully treated. Prine was resistant, but a threatening call from Sam sealed the deal, and saved his life.

The treatments transformed Prine physically. He lost a chunk of real estate between his head and shoulder and had his bite refashioned. He also has put on a bunch of weight. But if someone else in the same situation might dwell on the down side, or wear a turtleneck (“That’s just not John,” says Bunetta), Prine plays up the positives.

“I’m sure part of it is being grateful for being able to do it at all, but a lot of it was, ‘Jeez, I have this new voice,'” he says. “My voice dropped as a result of the treatments, and it seemed friendlier to me than ever; it seemed like an extension of my conversational voice. Maybe I always had it and didn’t know it, because I know I used to talk way down here, and then I’d go to sing and I’d sing the song where I wrote it, I’d sing it way up here, and through my nose on top of that.

“Anyway, I had to change the key on all the songs because of my new voice, which turned out to be a real gift for me. The old songs became new to me again. If I had known all I had to do was change the key, I woulda done that years ago. From day one since I started performing again, it’s never been the same for me onstage. To have that sack full of songs and to discover them again — I couldn’t ask for anything better.”

Prine, who re-recorded his early classics for his 2000 album Souvenirs — not only to test-drive his new voice, which sometimes slurs a bit, but also to own masters of the songs — enjoys telling of how he laughed off his doctors’ offer to put a shield around his vocal cords during radiation treatments. “I said if I could talk, I could sing, because that’s all I could do in the first place. I play the guitar and talk, and talk a little faster, and hold a note at the end of the line, and I said that basically became my singing voice. My definition of singing is how spirited it is, how believable, not whether or not you can hit the note.”

As much as he runs down his vocal talents, having fallen so short of his childhood desires to croon like Jim Reeves, he knows, like so many other craggy-voiced songwriters Bob Dylan gave license to trill, that the power of his personal expression transcends whatever stylistic i’s he can’t dot or t’s he can’t cross. Opposite a full-bodied weeping willow such as Melba Montgomery, his instrument can seem a bit twiggish, but when he’s in his own backyard, in his element, he’s an untouchable.

Covers of his songs are many and varied, including Bonnie Raitt’s “Angel From Montgomery”, Bette Midler’s “Hello In There”, Johnny Cash’s “Unwed Fathers”, the Everly Brothers’ “Paradise”, Norah Jones’ “That’s The Way That The World Goes ‘Round”, and let’s not forget Swamp Dogg’s “Sam Stone”. But most of his interpreters play things too straight up, if not with too much sentimentality (something Prine himself has been accused of), to serve his rascally sensibility and oblique poetry.

Kris Kristofferson, one of Prine’s early champions, marvels over the elusiveness of lines like, “As soon as I passed through the moonlight/She hopped into some foreign sports car” (from “The Great Compromise”). Joe Ely, who came under Prine’s influence while with the original incarnation of the Flatlanders, admires his craft. “It’s one thing to write lyrics and another to have the whole melody and the way you sing it work with the song,” Ely observes. “When John finishes a song, he knows how to present it. He figures it out while he’s putting it together. There are very few people who can do that.”