With ‘Lover,’ Noah Gundersen Mines Pop Confessionalism

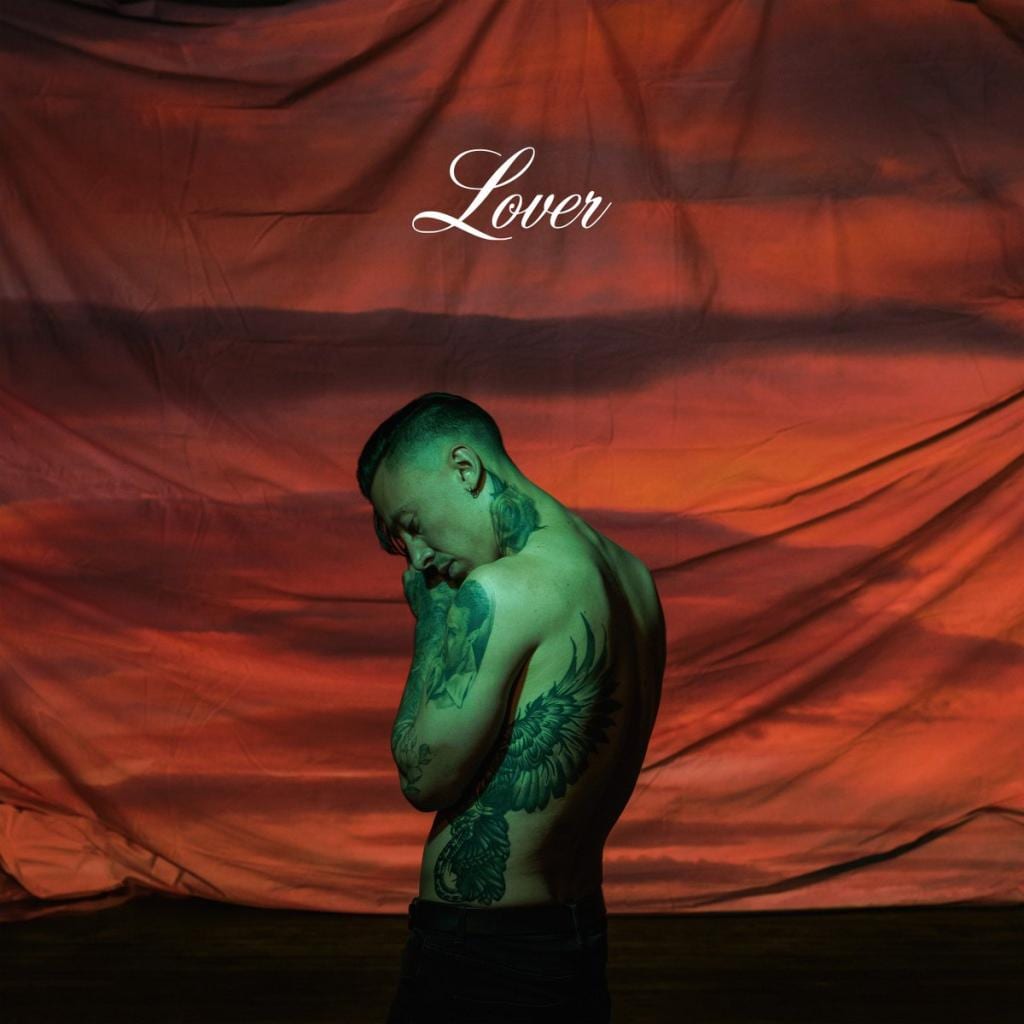

Emerging in the 2000s with a series of EPs and then his first full-length album, The Ledges (2014), Noah Gundersen drew from the atmospherics artists such as Gregory Alan Isakov and the melodic and vocal sensibilities of Ryan Adams, lyrical proclivities ranging from the quotidian to the apocalyptic. If 2017’s White Noise highlighted his affinity for mainstream territory — au courant blends of electronica and melodicism — his new album, Lover, shows the singer-songwriter marginalizing his folkish roots, adopting stylistics more reminiscent of Maroon 5 than Nick Drake, more Harry Styles than early Sam Beam, a consummate embrace of commercial-friendly gestalts.

“But when I think of Robin Williams at the end of his rope / It makes no difference what you’re making, the reaper makes the final joke,” Gundersen sings on Lover’s opening track, addressing the ineluctability and, in most cases, inelegance of death. Released earlier this summer as a single, “Robin Williams” showcases Gundersen’s ability to balance funereal content and tones with a hook-y, even ebullient melody — lyrics oblique enough to be intriguing, yet direct enough to elicit a singular response.

The title song addresses those fundamental wounds, some originating in childhood, that we often mask with romance (or substances): “I don’t need no lover / I need a mother to come to my room / I don’t need no father / I need an ocean to carry my mood.” Though lyrically solemn, the song employs an airy melody that wouldn’t be out of place on an Ed Sheeran or Ben Howard track.

“Out of Time” offers a moody verse that transitions into a falsetto chorus wrapped in reverb-y accents. On “Audrey Hepburn,” Gundersen displays his skill for portraiture: “Megan I have worn you like a blanket in the cold / Shivering on your barstool, soaked down to the bone / Breaking your attention from across a crowded room / Where you pour expensive poison for rich boys to consume.” As the song progresses, dual vocals (Gundersen and Whitney Ballen) create a doubling effect that brings to mind Elliott Smith, lo-fi atmospherics (conversational voices and sounds of everyday life) juxtaposed with a well-textured and well-produced vocal and instrumental mix.

The use of autotune on “Older” will remind some listeners of recent Bon Iver, a melancholy, possibly sentimental take on the aging process. The track features a complex interweaving of ambience, instrumentation, and electronics, the album’s most orchestral composition. “Wild Horses” is the folksiest track on the project, opening with a strumming acoustic, Gundersen’s vocal conjuring the earnestness of Edwin McCain or Darius Rucker. “All My Friends” offers a stereotypical yet vivid snapshot of many people’s 20s (“still getting high school drunk,” “[trying to] relieve that pressure”), the limbo between teendom and being an adult. It isn’t hard to visualize thousands of teary-eyed fans waving their arms in the arena.

At the heart of Noah Gundersen’s evolution is an ongoing quest — mostly successful, occasionally not — to reconcile a uniquely tragic vision with buoyant formulae; i.e., über-confessionalism (think Plath, Sexton) channeled through quintessentially accessible (pop) sounds and structures. The tracks on Lover cover a wide aesthetic, emotional, and musical spectrum. In addition, Gundersen’s current trajectory seems replete with creative possibilities and options, an indication of vital work to come.